SANJEEV SANYAL

Land of the Seven Rivers

A Brief History of Indias Geography

Contents

To Varun and Dhruv,

that they may know where they came from

Introduction

As we make our way through the second decade of the twenty-first century, India is undergoing an extraordinary transformation. This is visible everywhere one looks. After centuries of relative decline, the Indian economy is reasserting itself. The result is an urban construction boom that defies imagination. Almost overnight, whole new cities are being built. Nowhere is this more true than in Gurgaon where I lived as I wrote this book. Where there had been wheat and mustard fields till the mid-nineties, there are now malls, office towers, apartment blocks and highways. Even as I write these words, I watch yet another condominium block rise up.

Boomtowns like Gurgaon, however, are merely one facet of the changes being experienced by India. Mobile telephones and satellite television, combined with rising literacy and affluence, have changed the dynamics and aspirations of rural and small-town India. The children of farmers are moving to the cities in the millions. By all accounts, India is likely to become an urban-majority country within a generation and its cities need to prepare for the influx of hundreds of millions of people. Existing cities will expand, new cities will rise and villages will be transformed. The old ways are clearly declining.

The economic rise of India is to be welcomed in a country that has long been plagued by poverty but change is not without its price. Natural habitats are being drastically altered and often ravaged by activities like mining, sometimes legal but often illegal. I am told that there are now barely 1706 tigers left in the wild. Dams and canals are altering the fortunes of sacred rivers even as factories and cities empty their untreated waste into them. As urbanization and modernization churn the population, communities are being torn apart and with them we are losing old customs, traditions and oral histories. Many reminders of the countrys history are being paved over by new highways and buildings.

I am very conscious that we live in a time of rapid change. However, it is important to remember that India is an ancient land. In the long course of its history, it has witnessed many twists and turns. Cities have risen and then disappeared. There have been golden periods of economic and cultural achievement as well as periods of defeat and humiliation. Over the centuries, many groups have come to India as traders, invaders and refugees, even as Indians have settled in foreign lands. The country has endured dramatic changes in climate and natural habitat. In short, India has been through all this many times before.

The scars and remnants of this long history are scattered all over the landscape. If one cares to look, they will stare back even from the most unlikely of places. New Delhi, the national capital, is a good example. It is merely the latest in a series of cities to have been built on the site. Amidst the frenetic pace of modern life, the older Delhis live on in grand ruins, place-names, urban villages, traditions, and sacred sites. Even older are the ridges of the Aravalli Range, arguably the oldest geological feature on Earth.

Much has been written about Indian history but almost all of it is concerned with sequences of political eventsthe rise and fall of empires and dynasties, battles, official proclamations and so on. These are undoubtedly important but I have little to add to what has already been said about the emperor Akbars mansabdari system or the Morley-Minto reforms of 1909. However, history is not just politicsit is the result of the complex interactions between a large number of factors. Geography is one of the most important of these factors. Moreover, this relationship works both waysjust as geography affects history, history too affects geography.

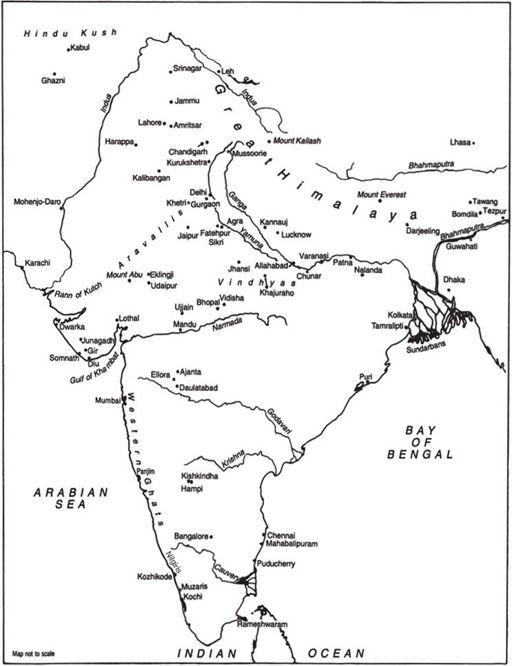

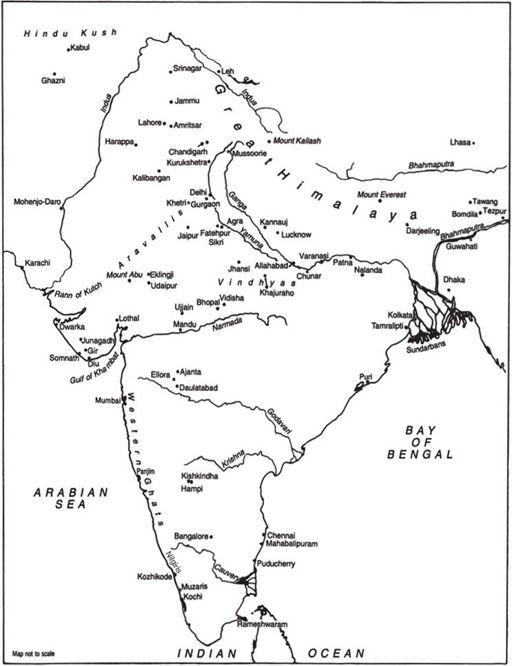

This book is an attempt to write a brief and eclectic history of Indias geography. It is about the changes in Indias natural and human landscape, about ancient trade routes and cultural linkages, the rise and fall of cities, about dead rivers and the legends that keep them alive. Great monarchs and dynasties are still important to such a history but they are remembered for the way in which they shaped geography.

Thus, the book focuses on a somewhat different set of questions: Is there any truth in ancient legends about the Great Flood? Why do Indians call their country Bharat? What do the epics tell us about how Indians perceived the geography of their country in the Iron Age? Why did the Buddha give his first sermon at Sarnath, just outside Varanasi? What was it like to sail on an Indian Ocean merchant ship in the fifth century AD or to live the life of an idle playboy in Gupta-era Pataliputra? How did the Mughals hunt lions? How did the Europeans map India? How did the British build the railways across the subcontinent? The process of change still goes on and, in the last chapter, we will look at the huge shifts being caused now by the process of urbanization and rapid economic growth.

While the primary focus of this book is on the history of Indias geography, the converse, too, is a secondary theme that runs through the book. In other words, the book is also about the geography of Indias history and civilization. One cannot understand the flow of Indian history without appreciating the drying up of the Saraswati river, the monsoon winds that carried merchant fleets across the Indian Ocean, the Deccan Traps that made Shivajis guerilla tactics possible, the Brahmaputra river that allowed the tiny Ahom kingdom to defeat the mighty Mughals and the marshlands that dictated where the British built their settlements. Furthermore, the book will also consciously bring out the technologiesfrom kiln-fired bricks and ship building to map-making and railwaysthat have influenced the way we think of India.

The very idea of India, its physical geography and its civilization, has evolved over the centuries. Yet, despite all these changes, it is astonishing how Indias civilizational traits have survived over millennia. The ox-carts of the Harappan civilization can still be seen in many parts of rural India, essentially unchanged but for the rubber tyres. The Gayatri Mantra, a hymn composed over four millennia ago, is chanted daily by millions of Hindus. This is not just about longevity but about a civilizational ability to take along an incredible mix of ideas, cultures and lifestyles that, despite their apparent differences, are still a part of the overall patchwork. There are still remote tribes that retain a huntergatherer lifestyle that has changed little since the first humans entered the subcontinent. This is not just about a lack of development. The Sentinelese tribe of the Andaman Islands deliberately retains its Stone Age culture and ferociously resists outside contact despite repeated efforts by the government. Who are we to civilize them?

One of the persistent misconceptions about Indian history is that Indians have somehow never conceived of themselves as a nation and, consequently, never cared about their history. This idea was often repeated by colonial-era officialdom for obvious political ends. As Sir John Strachey put it in the late nineteenth century, The first and most essential thing to learn about Indiathat there is not, and never was an India. Half a century later, Winston Churchill would echo the same point when he said that India is a geographical term. It is no more a united nation than the equator. A corollary to this point of view was the argument that since Indians were never conscious of their nationhood, they did not care for their history (or their freedom).

Next page