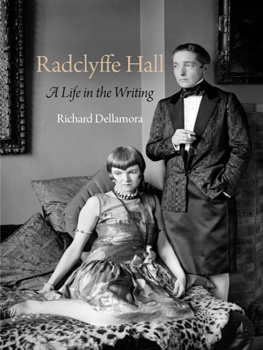

Radclyffe Hall

A Life in the Writing

Richard Dellamora

PENN

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia

A volume in the Haney Foundation Series, established in 1961 with the

generous support of Dr. John Louis Haney.

Copyright 2011 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dellamora, Richard.

Radclyffe Hall : a life in the writing / Richard Dellamora.

p. cm. (Haney Foundation series)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN: 978-0-8122-4346-8 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Hall, RadclyffeCriticism and interpretation. 2. Lesbianism in

literature. 3. Spiritualism in literature.

PR6015.A33 Z635 2011

823'.912 B 22

2011010285

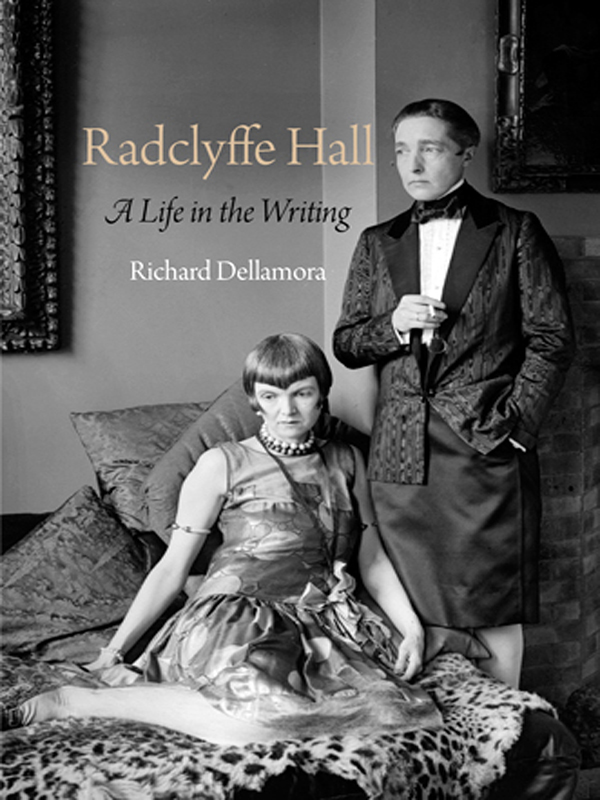

Overleaf: Radclyffe Hall and Una Troubridge, 1927.

Hulton Getty/Liaison Agency.

I never write my own life,

I could not.

Radclyffe Hall

ILLUSTRATIONS

PREFACE

Since the 1970s, the memory of Radclyffe Hall has depended for the most part upon one novel and its place in her work as an activist on behalf of the social rights of women with sexual and emotional ties to other women. The effects of near exclusive focus on The Well of Loneliness (1928) and related court cases has been to impose upon Hall a biographical trajectory in which the single overriding feature of her life is her emergence as an early leader in the struggle for gay and lesbian rights. Hall herself, however, rejected this view and attempted in subsequent writing to recapture the less specialized readership of her earlier fiction. My interest is to consider the factors in relation to which this particular trajectory arose. In recent years, the development of the field of queer theory has made possible a view of Hall that gives due emphasis to three concerns that primarily engaged her: namely, female same-sex desire, engenderment, and spirituality.

A study of the five short books of poetry with which she began her literary career indicates that her signature from the start carried with it the affirmation of sexual and emotional ties between women. For Hall, this impulse was married to an equally strong desire to define herself as an artist and to mark out the contours of her personal life, directly and indirectly, in her published and unpublished poetry, fiction, essays, and lectures. Equally, all the metaphysical turns in Hall's life are related to her ties with female partners or lovers: namely, her conversion to Roman Catholicism in 1912; the six years she devoted to psychical research following the death of her first long-term partner, Mabel Veronica Batten; the adherence to Spiritualism implicit in the years of sances with Mrs. Gladys Osborne Leonard, a prominent British medium; the theosophical narrative structure of A Saturday Life (1925); and the desire for interpersonal fusion that characterizes the letters to Evguenia Souline in the final decade. In this context, the traditional view of the primary significance of Hall's sexual interests may appear to be confirmed. It remains the case, however, that whether one begins with Hall's desire for other women or with her concern with cross gender or with mystical states, each leads to the others.

Hall was a charismatic figure with a complex affective and sexual life. This reality, combined with her courting of scandal and the exclusive attention directed by critics to The Well of Loneliness, accounts for the fact that almost all of the books published about her have taken the form of biography or biographical memoir. Hall became a celebrity as part of the enterprise of developing a lesbian public culture in the early twentieth century, but this apparently straightforward statement masks complexities. For instance, I know of no instance where Hall uses the word lesbian to designate a member of a particular sexual minority. Rather, she seems to have written at almost the last possible moment in the twentieth century in which the public affirmation of sexual and emotional ties between women could be made without using that word. Hall uses three other terms instead, each drawn from a different history in the development of discourses about female same-sex desire. In the course of this book, the reader will find Hall's interest in desire between women frequently characterized in terms of Sapphic culture, derived from French Aestheticism, as that culture came to exist in male and female lives and writing of the late nineteenth century in France and England. Equally important is the highly developed Sapphic culturecomplete with rituals, a sacramental life, mythography, sacred texts, heroes, and martyrsthat Natalie Barney built around herself in a high-profile experiment in Paris after 1900. In the fiction of the 1920s, Hall participated in and reported on this Parisian scene. By this means, she joined Barney's venture; but, as I have mentioned, from the early years of the new century, Hall was already conducting her own experiments in Sapphic culture.

Second, Hall associated herself with modern sexual science in its efforts to define what later came to be called the lesbian subject. Well versed in popular accounts of Freud,

Third, as Ruth Vanita and others have observed, there is a long tradition in which Marian and Christic references signal both female-female and crossgendered female-female desire. In recent years, Frederick S. Roden, Ellis Hanson, and other writers have made important contributions to the analysis of this discourse. All three modes of addressSapphic, sexological, and Catholiccontributed to articulating a complex understanding of sexual and emotional ties between women. And all three characterize Hall's approach at specific moments.

As author and individual, Hall's life was an exercise in new ways of being in the world. Unfortunately, the genre of biography is not well suited to experiment. Biographies, at least marketable ones, depend upon novelistic narratives, well-defined characters, and familiar emotions and moral views. The ideological effect of biographies is to reinforce these views by repeating them. Facts and situations may be novel but not the ideas, affects, and emotions with which they are presented. As a result, it has been necessary to write this book against the genre of Hall biography. On occasion, I take explicit exception to how the rules of the genre operate in a particular biography. Nonetheless, because Hall's experiment is one in life and writing, I am in debt to the writers of her biographies, especially to Michael Baker, whose work is often paraphrased in later biographies, and Sally Cline, whose 1997 biography for the first time locates Hall's start as a writer within the context of an accomplished and adventurous group of female artists, Sapphists, and feminists.

Cline makes clear the collaborative character of Hall's art from the outset. Collaboration too is not well suited to conventional biography. Biographies of writers usually focus on one or at most two individuals. Moreover, Hall and her second long-term partner, Una Troubridge, invested in the ideology of singular artistic genius. Despite the apparent contradiction, however, without Troubridge, Hall is unlikely to have produced the chain of literary successes that she enjoyed in the 1920s. Moreover, Troubridge shares responsibility for the outspoken activism of