Though so many countries and cities have been minutely described by geographers and historians yet this my residence of Constantinople remains undescribed. So said Sultan Murat IV to an assembly of scholars in the year 1638, as quoted by the contemporary Turkish traveller Evliya Efendi. This imperial complaint eventually led Evliya to write his own account of life in Istanbul during Murats reign and those of his immediate successors. Evliyas description of the city is contained in two volumes of his Seyahatname, or Narrative of Travels, which he completed in about 1680. Many books have been written about Istanbul since then, but nothing which is comparable to Evliyas narrative, which recreates the colourful spectacle of life in the capital of the Ottoman Empire in the closing years of its golden age.

For Evliya was superbly equipped and situated to be the chronicler of that most fascinating period in the citys history. He was in his time a soldier, sailor, diplomat, historian, mezzin, goldsmith, writer, poet, singer, musician, and, above all, a traveller; equally at home in throne-room or taverna; an intimate of sultans and mighty pashas; a friend of poets, divines and sainted idiots; a comrade of common soldiers and humble workmen; familiar with all the exotic avenues and arcane byways of Istanbul life; his keen eye always looking for the curious sight, the odd character, the pleasurable walk or the panoramic view; his musicians ear listening for the sound of a street-hawkers cry, the melodies of a dervish song, the ditty of a drunken sailor; his gourmets taste seeking out the most delicious food in town, and, although he claimed to be abstemious, the finest wines; his sharp nose sniffing out the earthy odours of Istanbul trade and commerce. Thereby he became a peripatetic encyclopaedia of the street-lore and folk history of his beloved city. Much has happened here in the past three centuries, but when we compare contemporary Istanbul with Evliyas town we see that its basic character has not really changed. Although the eunuchs and the Janissaries have gone, the sights and sounds and smells in the streets of Istanbul are much the same as those which Evliya records in the Seyahatname.

My own book is an attempt to evoke the spirit of the Istanbul that I have known, just as Evliya did for the city of his day. I have tried to do this through a series of brief sketches of Stamboul scenes. (I have here used the old-fashioned name of the city, as seeming more appropriate for the atmosphere I have tried to create.) Evliya Efendi appears and reappears throughout these sketches, for in his Seyahatname he touches on virtually every aspect of the citys life. So in my own wanderings through Stamboul I have constantly had him by my side, he comparing his town with mine, like an eccentric companion-guide. And I have often interwoven my narrative with that of Evliya Efendi, trying to bridge the gulf of years that separates his time from ours, so as to reveal something of the continuity of human experience which seems to exist in this ancient city.

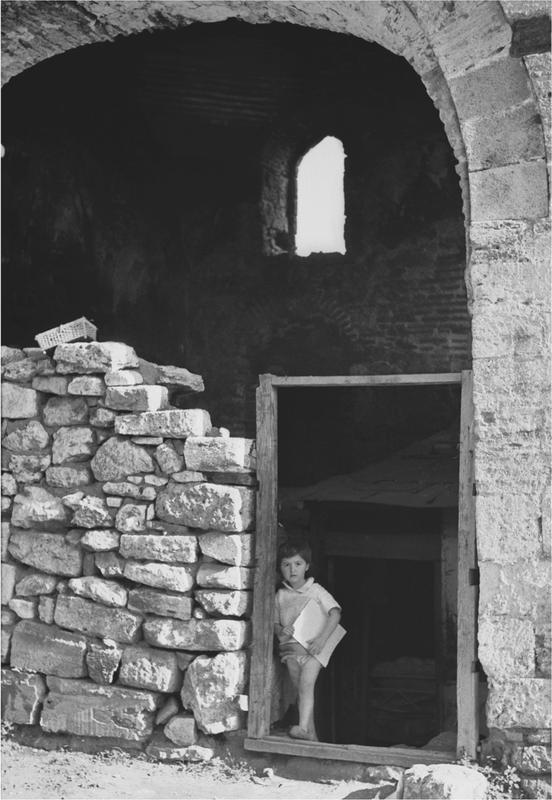

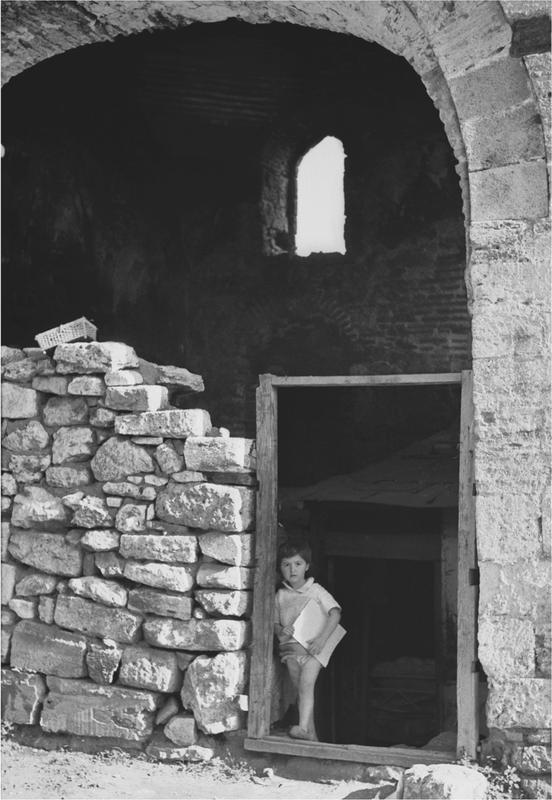

These sketches were written over the course of the dozen years during which we have lived in Stamboul, and so many of them may now seem somewhat dated. For the scene has changed, and many of the characters have departed, some never to return. You will search in vain for the Albanian Flower-Pedlar and the Grandfather of Cats; Nazmis Caf and the Taverna Boem have closed their doors for ever; and some of our street-poets and wandering minstrels now sing and play here no more. Nevertheless I have made no attempt to update the sketches, for they and the photos by Sedat Pakay are a picture of the city we knew and loved in years past, the old Stamboul of our memories.

I would like to express my appreciation to William Edmonds of Redhouse Press for his help and encouragement in putting together Stamboul Sketches. Thanks are also due to Michael Cain for editorial work, and to Alan and Sue Ovenden, and Sara Rau for many helpful suggestions.

J. F., I STANBUL , N OVEMBER 1 ST 1973

Child standing in front of the Byzantine city walls

Evliya, the son of Dervish Mehmet, was born in Stamboul on the tenth of Muharrem in the year after the Hegira 1020 ( AD 1611) in the reign of Ahmet I. As Evliya writes in the Seyahatname, in the section entitled Anecdotes of the Youth of the Author, At the time when my mother was lying in with me, the humble Evliya, no fewer than seventy holy men were assembled at our house. At my birth the sheikh of the Mevlevi dervishes took me into his arms, threw me into the air, and catching me again, said, May this boy be exalted in life! After relating other anecdotes concerning these scholars and divines and the comments they made at the time of his birth, Evliya concludes with this characteristic statement: The short subject of this long discussion is to show that I, the humble Evliya, was favoured with the particular attention of these saints and holy men.

Evliya came from an old and distinguished Turkish family which traced its lineage back to Sheikh Ahmet Yesov, who was the teacher of Hadji Bekta, the founder of the Bektai order of dervishes. Evliyas father had been Standard-Bearer in the army of Sleyman the Magnificent, and was at the Sultans side when he died at the siege of Sziget in 1566. During the reign of Ahmet I, Dervish Mehmet became Chief of the Goldsmiths, a trade to which Evliya was apprenticed when he was a young man. His uncle and patron, Melek Ahmet Paa, was a Grand Vezir in the reign of Murat IV (162340) and Evliya accompanied him on many of his missions and campaigns. His grandfather, Yavuz Ersinan, was Standard-Bearer in the army of Sultan Mehmet II and was present when Constantinople fell to the Turks in 1453. (Those two generations of Evliyas family span at least two centuries; either his forebears were incredibly long-lived or the intervening ancestors were foreshortened in the telescope of Evliyas imagination.)

After the Conquest, Yavuz Ersinan was allotted a plot of land in Unkapan (the Flour Store), the district around the Stamboul shore of the present-day Atatrk Bridge. The mosque which he founded at that time, about 1455, is still standing and in use; it is probably the oldest surviving mosque in the city. It is called Sarclar Camii, the Mosque of the Leather-Workers, after the artisans who have practised their trade in that neighbourhood for centuries. When Yavuz Ersinan died he was buried in the garden behind his mosque, and his moss-covered tombstone can still be seen there today. But the family homestead in which Evliya was born has vanished without a trace.

When he was six years old Evliya was enrolled in the school of Hamid Efendi in the section called Fil Yokuu, the Path of the Elephant. (The street from which this section takes its name is still in existence, winding up from the shore of the Golden Horn to the heights above Unkapan.) Evliya studied in Hamid Efendis school for seven years, during which his tutor was Evliya Mehmet Efendi, Chief Imam in the court of Sultan Murat IV. While there he studied calligraphy, music, grammar and the Koran, in the reading and singing of which he particularly excelled. After leaving Hamid Efendis school Evliya continued his studies with Evliya Mehmet Efendi, who appears to have given him a remarkably broad education. As Evliya once remarked to Murat IV: I am versed in seventy-two sciences; does your majesty wish to hear something of Persian, Arabic, Syriac, Greek or Turkish? Something of the different tunes of music, or poetry in various measures? To which the Sultan replied: What a boasting fellow this is! Is he a Revani (a prattler), and is this all nonsense, or is he capable of performing all that he says? We have only Evliyas own testimony to prove that he was no idle boaster, but an imaginative elaborator of the truth.

![Freely Stamboul sketches: [encounters in old Istanbu]l](/uploads/posts/book/201354/thumbs/freely-stamboul-sketches-encounters-in-old.jpg)