C ONTENTS

Appendix I: |

Appendix II: |

Appendix III: |

Appendix IV: |

Appendix V: |

Appendix VI: |

by The Rt. Hon. The Lord Mayor of London, Alderman Michael Bear

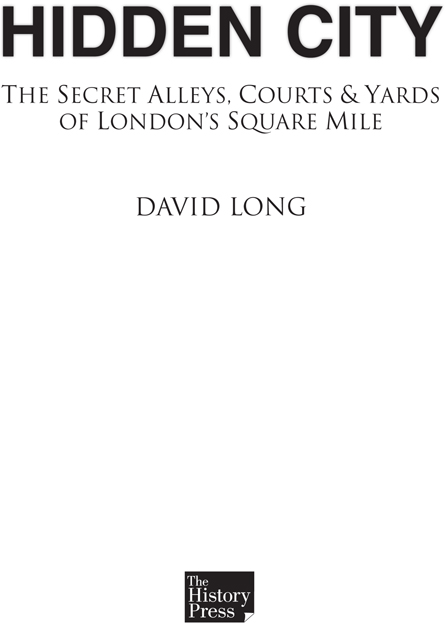

A ll great cities evolve over time, and must continue to do so in order to thrive. The City of London is certainly no exception to this, although those of us who live and work within the historic Square Mile or who simply love its astonishingly rich mix of old and new are especially lucky in that the uniquely varied layout of its streets, alleys and narrow passageways has remained essentially unchanged for many hundreds of years.

It seems incredible now, but this precious survival was by no means always guaranteed. After the Great Fire of 1666 there were plans to create a new, more regular and ordered layout of the sort commonly found in many continental capitals. Later on, the terrible destruction of the 1940s provided yet another opportunity for those who wished to tear down what remained and start again but happily this too was resisted.

Today, as a result, those who walk the streets of the City can follow the same basic street pattern as their medieval forebears. Before the Great Fire, before the Blitz, and long before Big Bang and all that followed that more technological but equally seismic change, London comprised a veritable maze of narrow passages, secret squares and tiny courtyards and it is these that form the subject of David Longs delightful and fascinating book.

As someone who has spent much of his professional life as a civil engineer I know that preserving these important little spaces can present extraordinary challenges to business and to those of us charged with meeting the changing demands of the global economy. But as someone who has worked in and around the Square Mile for much of that time and who now has the very real honour of serving as its 683rd Lord Mayor I know, too, how crucial it is that we respect the ancient fabric of the City while working to fulfill our other obligations to keep London and the City of London at the forefront of a fast-moving and rapidly changing world.

I came suddenly upon such knotty problems of alleys, such enigmatical entries, and such sphinxs riddles of streets without thoroughfares, as must, I conceive, baffle the audacity of porters, and confound the intellects of hackney-coachmen. I could almost have believed, at times, that I must be the first discoverer of some of these terrae incognitae, and doubted whether they had yet been laid down in the modern charts of London.

Thomas de Quincey, The Pleasures of Opium (1821)

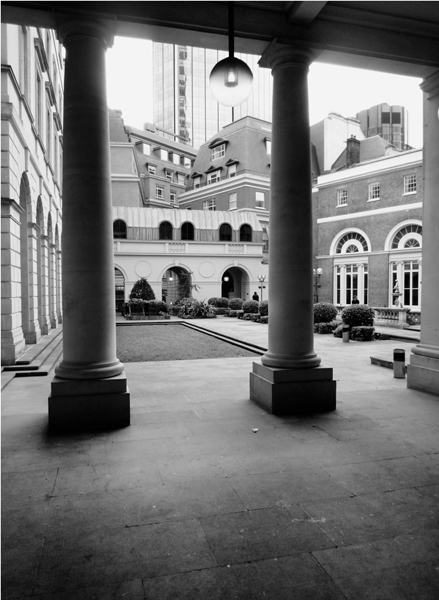

I nsulated from the noise, from the seemingly endless development and redevelopment of the historic Square Mile and above all from the aggressively commercial bustle of the larger streets and traffic-clogged thoroughfares is a second, almost secret City of London.

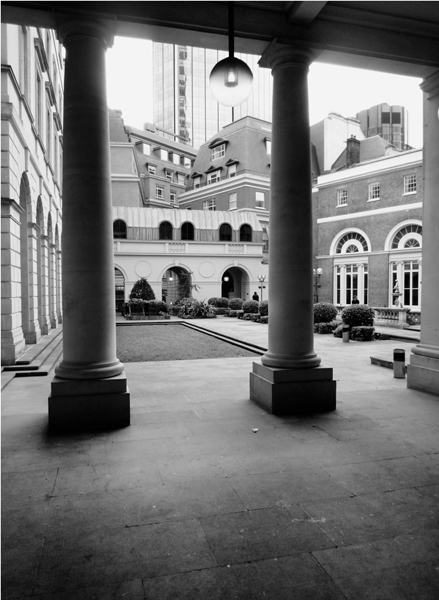

Comprising a sometimes bewildering tangle of narrow alleyways, courtyards and unexpected dead-ends, many of them medieval in origin even if they sadly no longer give this impression, this second, hidden city is a compact but intriguing place. Dotted with blue plaques and strange statues and memorials to the forgotten, often leading the explorer to little gardens built around Roman remains and derelict or discarded churches, this maze of little cut-throughs, shortcuts and byways conceals many old and even timber-framed buildings which have somehow survived against the odds, and offers walkers the chance to stumble upon some of the most unexpected and charming places to eat and drink in central London.

Above all, though, to appropriate the words of one of Londons more recent biographers, it is somewhere you discover that commonplace traffic, the swinish rush of metal, is happening somewhere else. Also, to quote another, somewhere one begins to understand how the area stretching from Tower to Temple really is made for walking a city of small streets and sudden vistas, of unexpected alleys and hidden courtyards which cannot be seen from a bus or car.

Though famously rebuilt after the Great Fire of 1666, and again and again in the centuries which followed, the basic streetscape of Londons financial heart still reflects its medieval layout and it is this that best conveys the oft-cited impression of it being truly a city within a city. The old gateways into the bustling medieval settlement may be long gone, the Roman wall has almost entirely (but not quite) disappeared beneath warehouses, offices and apartments, and towering new developments continue to be thrown up and torn down with bewildering rapidity. But stepping behind the modern faades, or squeezing through narrow passages between the vast glass ziggurats of twenty-first-century commerce in search of a favourite Wren church or simply somewhere quieter to sit and think, it is still possible to come upon something ancient or timeless, and to enjoy the precious thrill of discovering somewhere centuries old yet to the beholder all but unknown.

I have seen the West End, the parks, the fine squares; but I love the City far better. The City seems so much more in earnest; its business, its rush, its roar, are such serious things, sights, sounds. The City is getting its living the West End but enjoying its pleasure. At the West End you may be amused; but in the City you are deeply excited.

Charlotte Bront, Villette (1853)

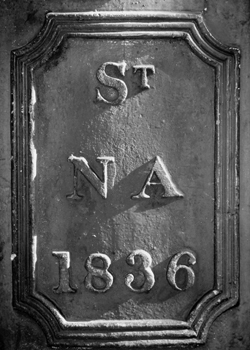

A BCHURCH Y ARD , EC4

Documented as long ago as the twelfth century, at which time it was known variously as Abchurch, Abbechurch, Habechirch and Apechurch. Each is almost certainly a corruption of upchurch, a reference to the rising ground on which the neighbouring church of St Mary Abchurch was built or to the fact that the church was upriver from the much larger St Mary Overie. Now Southwark Cathedral, this last named had been its mother foundation until the patronage was transferred to Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, during the reign of Elizabeth I.

What we see now, a small geometrically cobbled yard with circular stonework, was originally the graveyard to one side of which wartime bombing revealed a fourteenth-century crypt but in the way of such places it now provides a relatively peaceful spot on Abchurch Lane where office workers can kick off their shoes at lunchtime.

The church itself, with its elegant, shallow, painted dome, is regarded as one of Wrens prettiest; also among the most original even though the fabric sustained severe damage during the aforementioned bombing. The Grinling Gibbons reredos, for example, is particularly magnificent and is the only one in the City with documented proof of its complete authenticity. That said, it took five years to restore after being blown into more than 2,000 pieces during one particular raid. If the church is open take a look at the churchwardens pews too, which were designed to incorporate sword rests and dog kennels beneath the seats both once common enough features but which nowadays are only very rarely seen.

Next page