Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Music is an act of resistance.

A RTURO T OSCANINI

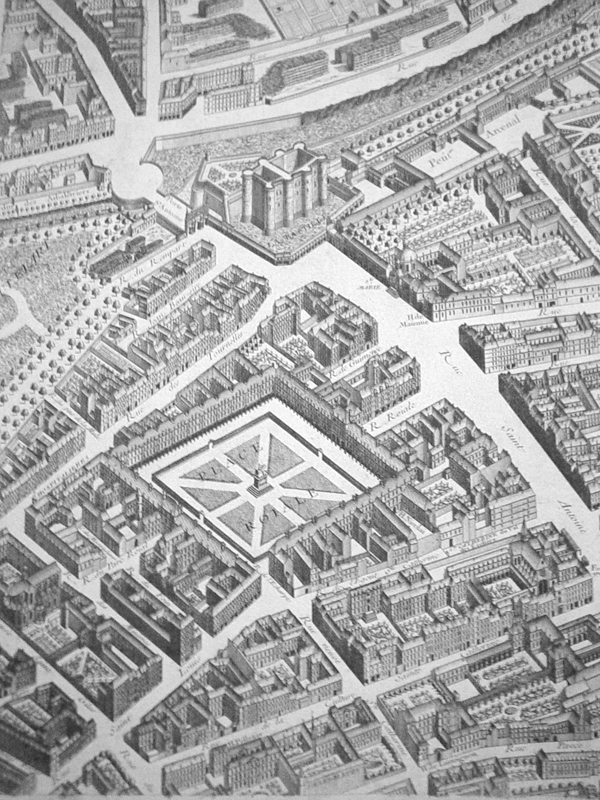

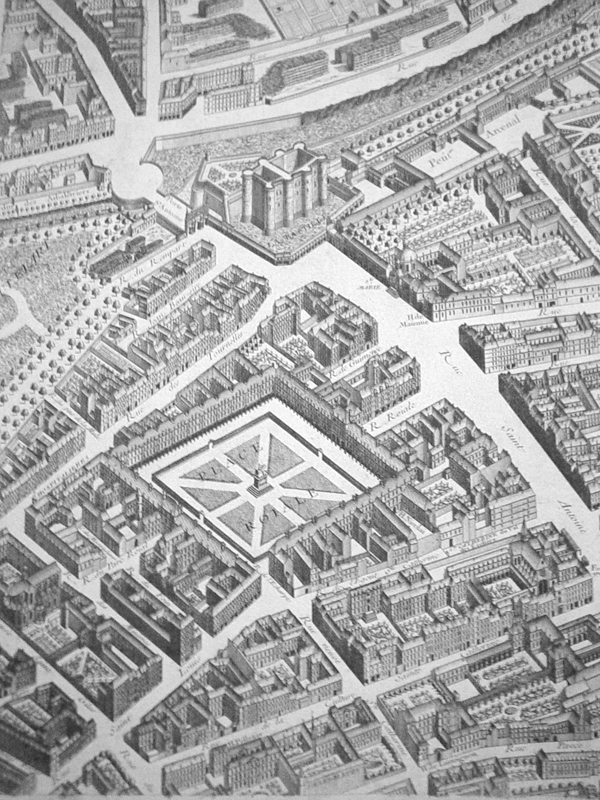

Detail showing the Place Royale and the Bastille, from the Plan de Turgot , started in 1734 and completed in 1739 under the direction of Michel-Etienne Turgot. COURTESY OF THE AVERY LIBRARY, COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY

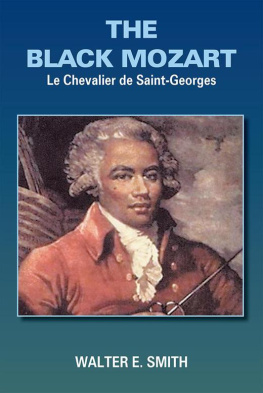

Lesser Antilles, Christmas Day, 1739 . Cool trade winds caressed the colonnaded mansion, but in an upstairs bedroom, its windows tightly shuttered, the atmosphere was stifling. A green haze enveloped the room, produced by smoke from burning cactus sticks. Barely visible in the gloom were dark European furnishings, the most striking of them an elegant dresser, over which hung a faded mirror, and a bed, on which lay a woman in labor.

Stiffen up now. Don you let up. Stiffen up now. Don you let up, a midwife urged the woman in labor, whose name was Nanon.

Squealing children chased one another around her bed, avoiding the swats of their scolding mothers, who were bustling about in the room.

Now don you let up!

The sound of chanting and singing drifted over from the sugar factory a few hundred yards down from the mansion, hidden behind a thick curtain of trees. There was also the pounding of drums and the beating of sticks against the trunk of a cedar tree. That morning these same musicians, slaves, had been herded to a mass celebrated by a Capuchin priest named Father Casimir. The sanctioning of the slave trade by the Church over a century earlier, in 1612, had not come without strings; in exchange for its blessing, the Church had been given greater opportunities to evangelize among the slaves, who were henceforth released from work on Sundays and feast days. For his part, Father Casimir had devised an efficient stratagem for ensuring control over souls as well as for preserving certain commercial interests that had recently been damaged by interfering Jesuits: Every slave visiting his confessional received a coin, which he was then free to go off and spend at the tavern.

No sooner were their churchly obligations fulfilled, however, than the slaves turned to pursuits that were decidedly un-Christian. Couples paired off to dance the calenda ; the rhythm of the drums grew ever wilder. More and more deafening, the music spread the length of the rue Case-ngreroughly, Slave Cabin Streetuntil there wasnt a room in the big house up on the bluff not bombarded by the din of drums.

Don you let up now!

In the room next door, a small group of Frenchmen were nervously chewing tobacco leaves and sipping beakers of rum. Among them was Monsieur Plato, a former customs officer from Bercy, near Paris. Platono one knew if such was his real name or a nickname given him by the slavesacted as the sugar plantations steward; he balanced the books with almost obsessive care. Also present was Georges Bologne de Saint-Georges, as he styled himself, the descendant of a line of slave-owning planters who worked one of the most prosperous estates on Guadeloupe. Between the two sat the most anxious of them all, the father of the baby due at any moment, Guillaume-Pierre Tavernier de Boullongne. In contrast to that of Georges Bologne, the de in Guillaume-Pierres name denoted the real thinglegitimate aristocratic descent

Don you let up!

Steam from the calabashes of boiling water that had been carried in by Clairon, a mixed-race woman in her twenties, swirled in the air and mingled with fumes from the burning cactus sticks, which, when lit, were thought to keep away insects. With a final, supreme effort, Nanon was delivered of a baby, a boy. The midwife exulted.

Ti moune la a, si Bon Di baille vie sant en peu di y ke grand missi!

If the good Lord gives him life and health, your baby be a fine gentleman! Then she ventured a prophecy. One day this boy meet the king of France!

Nanon, by general acknowledgment the most beautiful woman on the island of Guadeloupe, had just presented Guillaume-Pierre with a son. For Father Casimir, it was one more baptism to celebrate in a parish already growing by leaps and bounds; in a few months he would place the first stone in what would become Saint-Franois church. As this was Christmas Day, he decreed that the name Joseph was imperative. The name was all the more appropriate given that the patron saint of carpenters was also that of the so-called ngres talent, skilled Negroesthose who by dint of industry and expertise in some area had managed to free themselves from the drivers whip. Nonetheless, Josephs name would not be listed on the registry kept by the curate of nearby Le Baillif. His father might be a French nobleman, but Nanon was a slave, and the children of slaves were not recognized by the Church.

Only a year and some before, this youngest son of the Tavernier de Boullongne family line had been miles away from the Lesser Antilles, fighting grim battles against the Austrians and Prussians in the mud and drizzle of Flanders. But all that was in the past. Today, everything seemed to have turned out splendidly for twenty-nine-year-old Guillaume-Pierre, who had come to Guadeloupe vowing to earn his fortune and thereby to restore to his ennobled familys name a luster somewhat lost over the course of several generations. The Boullongnes were among the oldest families of French Flanders. They had had their ups and downs, however. At the beginning of the seventeenth century, for example, Louis de Boullongne was pursued by creditors, forced to flee the family seat, and set himself up in the town of Beauvais, north of Paris. Thinking it prudent, he had concealed his noble title, calling himself simply Tavernier. The ruse was a necessity for only a brief time; once the moneylenders threats had passed, Louis immediately began to display openly his title and coat of arms.

Doing so was more than a mere matter of pride. In France during this period, the rising bourgeoisie was engaged in a frantic quest for prestige; in their eyes, that aristocratic de in Louiss name was a real prize. He managed to marry off his son, Charles, to a nouveau riches daughter, whose dowry, in turn, enabled her husband to buy the position of personal lieutenant. Though most certainly not up to the level of what it would have been had it taken place in Versailles, the marriage ceremony had been celebrated by no less a personage than the bishop of Senlis. The same procedure was followed in due course by the grandson, GuillaumeGuillaume-Pierres fatherwho made equally clever use of his wifes dowry in 1708 by buying, admittedly at an extremely elevated price, the lucrative post of director of the salt tax in the town of Orlans.

While the upper-echelon aristocracy was parading around at court, looking down their noses at petty provincial nobles who, in their view, were debasing themselves by consenting to work, others had understood the direction in which the winds of change were blowing: money. At Versailles, dukes and barons were bankrupting themselves buying places among the front rank at the kings levee, the kings supper, or even the royal defecation. Meanwhile, in Paris, viscounts and petty marquises engaged in all kinds of speculation on the rue Saint-Honor and around the newly created place des Victoires, which was becoming a busy center of financial activity.