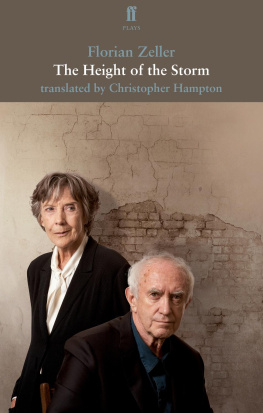

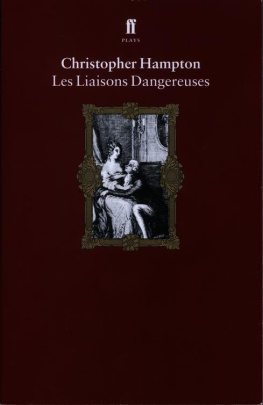

Hampton - Christopher Hampton Plays 1

Here you can read online Hampton - Christopher Hampton Plays 1 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2014, publisher: Faber & Faber, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Christopher Hampton Plays 1

- Author:

- Publisher:Faber & Faber

- Genre:

- Year:2014

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Christopher Hampton Plays 1: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Christopher Hampton Plays 1" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Christopher Hampton Plays 1 — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Christopher Hampton Plays 1" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The first of the plays here collected, chronologically speaking, is TotalEclipse, which was written in 1967 and which I now tend to think of, quite inaccurately, as the start of my career. This may be because my earlier writings, as schoolboy or student, were tentative experiments produced with the fluency and unselfconsciousness of an amateur, whereas this was a commissioned play more than likely to be professionally produced in front of paying customers; or because I had always considered my first play, WhenDidYouLastSeeMyMother?, given a Sunday-night production by the Royal Court Theatre and kindly (no doubt too kindly) received by the critics, to be a kind of dry-run for this much more ambitious piece; or even because the beginnings of a literary career and the potentialities of a writers life were in a sense the very subject I was examining in the play.

Language students at Oxford are given the option of extending their course for a year in order to work abroad and thus improve one or other of their languages. The amount of time I had spent in my second year mounting my plays, first in Oxford and then in London, combined with a no more than vestigial ability to speak German, made this in my case a necessity. My sympathetic and resourceful tutors found me a post in one of those vast municipal theatres which, then as now, possessed the resources to spend more money making armour for a single production than a comparable English theatre might receive in a year. So it was in Hamburg that I began writing the play, on 1 April to be precise, which seemed an appropriate date for so foolishly ambitious an undertaking.

My days in Hamburg were numbered. I had not enjoyed my time in the city: but, more to the point, there had been a misunderstanding about the nature of my Studienstelle, which turned out to be an honorary rather than a salaried position. I used this difficulty as an excuse to make an early getaway to Paris: where, under far more congenial circumstances, supporting myself with a translation job I was lucky to find, I pressed on into the summer with the play, which I eventually completed back in England in September.

Second plays were somewhat easier to place in those days than in the present, colder climate; still, production was by no means a foregone conclusion. The play had been commissioned by Michael Codron for the West End, but he soon decided, Im sure correctly, that its dubious commercial prospects could never justify its expensive requirements, in terms of size of cast and number of locations. The Royal Courts initial response, meanwhile, was cautious. I began to be tormented by the idea that the piece, which had been at the forefront of my mind now for a number of years, would never be performed. Then, one day, unexpectedly, Robert Kidd (who had directed my first play) and William Gaskill (Artistic Director at the Royal Court) arrived in Oxford and asked me to read the play to them. They settled into the only two chairs in the room: I sat up on the bed and read. At the end there was a long silence, before Bill said, All right, well do it.

This was not his only act of generosity towards me, as Im happy to be able to acknowledge here. He also invented a job for me, which was given the resonant title of Resident Dramatist in the (successful) hope of attracting support from the Arts Council. And so, two weeks after graduating, I arrived for the start of rehearsals on TotalEclipse and a formative two years work at the Royal Court.

The play was tepidly received at the time, but has since had more productions, I would guess, than any of my others; it seems to speak to a limited audience, but to speak to them loud and clear. Enthusiastic strangers have told me how much the play means to them in Utah and in Tokyo. For me, it was a means of posing a number of questions around a central puzzle, namely, what does it mean to be a writer? What could one reasonably hope to achieve? What were the pleasures and torments and what, if any, the responsibilities? Might one change the world, or would it prove beyond ones abilities even to change oneself? I still, of course, have no settled answers to these questions; but at that time it seemed that by examining two writers, Rimbaud and Verlaine, who had reached diametrically opposite conclusions on all these issues, despite their strong influence on one another, despite even the fact that they were lovers, some kind of fruitful internal debate might be triggered. For reasons I couldnt have explained then and still cant now, it seemed important to include the barest minimum of literary discussion in the play; to contemplate, in other words, only their lives and to leave with a scene which emphasized, despite the violence of their opposition, their fundamental solidarity as writers. Except in that final scene, I stuck firmly to the known facts (Did you plunder my book? Enid Starkie asked me when we met to discuss the play and seemed delighted when I admitted that I had), in the belief that reality will always yield more in the way of unexpected twists and poetic illumination than the most extravagant fictions.

Because the play is so central to me, I have had the greatest difficulty leaving it alone: consequently, there are four different published versions, two British and two American, of which I have chosen, for publication here, the third version, published after the revival at the Lyric, Hammersmith, in 1981, directed by David Hare. The fairly extensive changes for this production were made with Davids help and encouragement and I havent yet repented of them: but I still cant guarantee that this will remain my final version of TotalEclipse.

Molire was one of my special subjects at Oxford; and as I worked on LeMisanthrope, it occurred to me that in the climate of abrasive candour which characterized the late 1960s, Alceste would have been quite at home: whereas his opposite, a man concerned above all to cause no offence and be an unfailing source of sweetness and light, would very likely succeed only in raising hackles wherever he went. This notion was the germ from which ThePhilanthropist grew. As a setting which might be a modern equivalent of Molires world, in which clever and envious people with a startling amount of leisure time sit around demolishing their colleagues, thoroughly insulated against any external pressures or upheavals, the university naturally suggested itself. Nowadays, no doubt, the bubble has burst and universities are as subject as the rest of us to the harsh rigours of market forces; but in 1968, as campuses erupted all over Europe, Oxford seemed as sleepy as ever, cocooned and self-regarding.

These are the factors which anchor ThePhilanthropist to its time; but I was also interested in applying Molires method (comedy in which a character is examined in the light of a defining trait, such as hypocrisy or lust or avarice) to the study of what might technically be described as a virtue rather than a vice: compulsive amiability.

I began writing the play in February 1969, but pressure of work at the Royal Court, where I was now running the literary department, slowed me down and it was not until August, by which time I had agreed to stay on another year and acquired an assistant (and successor) in the shape of David Hare, that I was able to deliver. As with TotalEclipse, it was almost a year before the play reached the stage. During this time, I was happily employed providing new versions of UncleVanya (for Anthony Page at the Court) and

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Christopher Hampton Plays 1»

Look at similar books to Christopher Hampton Plays 1. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Christopher Hampton Plays 1 and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.