ALSO BY PAUL HENDRICKSON

Seminary: A Search

Looking for the Light:

The Hidden Life and Art of Marion Post Wolcott

The Living and the Dead:

Robert McNamara and Five Lives of a Lost War

Sons of Mississippi:

A Story of Race and Its Legacy

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2011 by Paul Hendrickson

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Portions of this work have appeared in different form in Mens Journal, The Washington Post, The New York Times, and Town & Country.

Owing to limitations of space, all acknowledgments for permission to reprint previously published material may be found following the index.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hendrickson, Paul, [date]

Hemingways boat : everything he loved in life, and lost, 19341961 /

Paul Hendrickson. 1st ed.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-70053-7

1. Hemingway, Ernest, 18991961. 2. Authors, American20th centuryBiography. 3. JournalistsUnited StatesBiography.

I. Title.

PS3515.E37Z628 2011

813.52dc22

[ B ]

2011003398

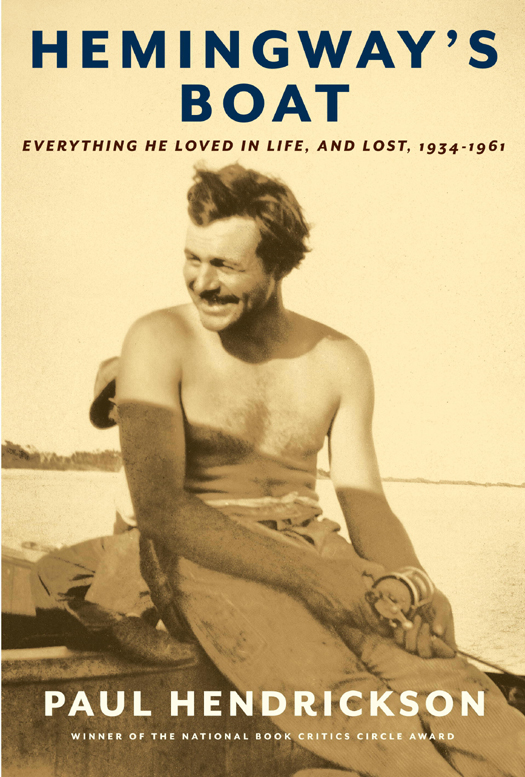

Jacket photographs courtesy of the Ernest Hemingway Collection/John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston Jacket design by Carol Devine Carson

v3.1

For Jon Segal,

editor and friend of three decades

CONTENTS

PART ONE

GETTING HER

PART TWO

WHEN SHE WAS NEW, 19341935

PART THREE

BEFORE

PART FOUR

OLD MEN AT THE EDGE OF THE SEA:

ERNEST/GIGI/WALTER HOUK, 19491952 AND AFTER

We have a wonderful current in the Gulf still in spite of the changes in weather and we have 29 good fish so far. Now they are all very big and each one is wonderful and different. I think you would like it very much; the leaving of the water and the entering into it of the huge fish moves me as much as the first time I ever saw it. I always told Mary that on the day I did not feel happy when I saw a flying fish leave the water I would quit fishing.

E RNEST H EMINGWAY , in a letter, September 13, 1952

Then, astern of the boat and off to starboard, the calm of the ocean broke open and the great fish rose out of it, rising, shining dark blue and silver, seeming to come endlessly out of the water, unbelievable as his length and bulk rose out of the sea into the air and seemed to hang there until he fell with a splash that drove the water up high and white.

Oh God, David said. Did you see him?

His swords as long as I am, Andrew said in awe.

Hes so beautiful, Tom said. Hes much better than the one I had in the dream.

Islands in the Stream

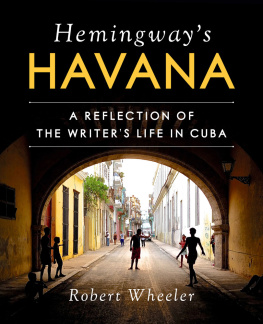

The dark is different in Havana. Its lit in a kind of amber glow, as if everythings on low generator, weak wattage. If you come into Cuba for the first time at nighttime, this feeling of strange darkness is intensified. Even the plane must sense thisor at least the pilotfor it seems to hang forever in a low, back-powered glide, as if working through a tunnel, before hitting the runway with a smack at Aeropuerto Internacional Jos Mart La Habana. You emerge from the Jetway into a terminal with the complexion of tea water. In the customs and immigration area, soldiers in the olive drab of the Revolution are walking large dogs. If your papers are in order, a latch on a door clicks open. Like that, youre on the other side of a lost world thats always been so seductively near and simultaneously so far.

PROLOGUE

AMID SO MUCH RUIN, STILL THE BEAUTY

On Pilar, off Cuba, midsummer 1934

MAY 2005. I went to Havana partly for the reason that I suspect almost any American without a loved one there would wish to go: to drink in a place thats been forbidden to American eyes (at least mostly forbidden) for half a century. So I wanted to smoke a Cohiba cigar, an authentic oneand I did. I wanted to flag down one of those chromeless Studebaker taxis (or Edsels or Chevy Bel Airs, it didnt matter) that roll down the Prado at their comic off-kilter angles, amid plumes of choking smokeand I did. I got in and told the cabbie: Nacional, por favor. I was headed to the faded and altogether wonderful Spanish Colonial monstrosity of a hotel where youre certain Nat King Cole and Durante are in the bar at the far end of the lobby (having just come in on Pan Am from Idlewild), and Meyer Lansky is plotting something malevolent in a poolside cabana while the trollop beside him rubies her nails. I also wanted to stand at dusk at the giant seawall called the Malecn that rings much of the city so I could watch the surf beat against it in phosphorescent hues while the sun went down like some enormous burning wafer. I wanted to walk those sewer-fetid and narrow cobbled streets in Habana Vieja and gaze up at those stunning colonial mansions, properties of the state, carved up now into multiple-family dwellings, with their cracked marble entryways and falling ceiling plaster and filigree balconies flying laundry on crisscrossses of clothesline.

Mostly, though, I went to Cuba to beholdin the flesh, so to speakErnest Hemingways boat.

She was sitting up on concrete blocks, like some old and gasping browned-out whale, maybe a hundred yards from Hemingways house, under a kind of gigantic carport with a corrugated-plastic roof, on what was once his tennis court, just down from the now-drained pool where Ava Gardner had reputedly swum nude. Even in her diminished, dry-docked, parts-plundered state, I knew Pilar would be beautiful, and she was. I knew shed be threatened by the elements and the bell-tolls of time, in the same way much else at the hilltop farm on the outskirts of HavanaFinca Viga was its name when Hemingway lived therewas seriously threatened, and she was. But I didnt expect to be so moved.

I walked round and round her. I took rolls and rolls of pictures of her long, low hull, of her slightly raked mahogany stern, of her nearly vertical bow. When the guards werent looking, I reached over and touched her surface. The wood, marbled with hairline fissures, was dusty, porous, dry. It seemed almost scaly. It felt febrile. It was as if Pilar were dying from thirst. It was as if all she wanted was to get into water. But even if it were possible to hoist her with a crane off these blocks and to ease her onto a flatbed truck and to take her away from this steaming hillside and to set her gently into Havana Harbor, would Hemingways boat go down like a stone, boiling and bubbling to the bottom, her insides having long ago been eaten out by termites and other barely visible critters?