Contents

About the Author

Gillian Tindall is the author of two short-story collections, six novels, and five other works of non-fiction. Both her novels and her non-fiction work have drawn inspiration from a highly developed sense of place and history. At various times, Bombay, Paris and rural France have all formed part of her essential subject matter; but London remains for her a source of enduring and inexhaustible interest. She lives in London with her husband.

Everything exists,

And not one smile nor tear,

One hair, one particle of dust, not one

Can pass away.

(William Blake)

plankes and lighter things swimme, and are preserved, whereas the more weighty sinke and are lost. And as with the light after Sun-sett at which time, clear in so many degrees etc; comes by and by the crepusculum then totall Darkness. In like manner it is with matters of Antiquities. Men thinke because every body remembers a memorable Accident shortly after tis done twill never be forgotten, which for want of registering at last is drowned in Oblivion.

(John Aubrey)

the desire of transmitting virtue to posterity does not torment the minds of the living, and what we read of the dead seems a fable, so different is the present practice of the world.

(Mary Evelyn)

List of Illustrations

All, except the illustrations 26 and 29 are engravings, and all by Hollar

Section of the Long View showing old London Bridge

Herald Angel from the Long View

View of Prague

Meyssenss portrait of Hollar with his tools

Henry van de Burg, after Meyssens

Drawing said to be after Rembrandt

Samples of Hollars small pictures of women

Near Andernach

Rdesheim

View of Greenwich

The courtyard of Arundel House

Albury, with the Arundel family taking a walk

Execution of Lord Strafford (detail)

Spring, with a view over Arundel House gardens

Summer, with a view from Arundel House up the river

Winter, with Cornhill in the background

One of Hollars muffs

Spring, with what may be Tart Hall in the background

Antwerp Cathedral

From the Arundel Collection: insects and shells

This is a good cat that does not steal

The rooftops of Windsor Castle

Supposed to be Margaret Tracy

William Dugdale

Covent Garden

Old St Pauls from Bankside section of the Long View

The Hollow Tree at Hampstead Heath

Old St Pauls interior, the nave

Part of the Restoration procession

The one surviving sheet of Hollars Great Map

Whitehall from the waterside, Lambeth opposite

Thomas Hobbes (detail), after J.-B. Caspar

The Waterhouse, Islington

London burning

The post-Fire map of London

Albury, the river Tillingbourne

Part of the pirates attack

Tothill Fields

Tomb of Henry VII in Westminster Abbey

New Palace Yard, Whitehall

Lambeth Palace and St Marys, from the river

Herald Angel from the Long View

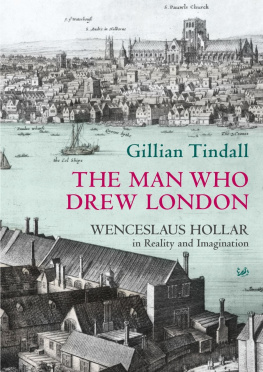

THE MAN WHO DREW

LONDON

Wenceslaus Hollar in Reality and Imagination

GILLIAN TINDALL

Authors Introduction, and Thanks

More than thirty years ago I bought for two pounds and ten shillings, I believe a seventeenth-century print of one of Hollars miniature Islington views. I bought it because I liked it and because I enjoyed thinking that this rugged, stream-crossed landscape was what lay beneath the streets about the Angel tube station. Hollars name had, till then, been unknown to me, though I began to realise that I had seen that discreet signature on other pictures of London, that indeed I had internalised his views of Stuart London so that they had become my own images of the city we have lost.

A few years later, lighting on a poster-sized reproduction of a cats head rendered in exquisite detail, I bought it as a decoration for a playroom. Only after I had got it home did I notice that this, too, was signed W. Hollar.

After that, charmed by an artist whose etching skills extended from fur and lace to the Gothic shadows of old St Pauls, and the depiction of the whole of London town in inspired birds-eye focus, I learnt more about him. I realised that I might one day want to write about him: but at the same time I came to know that, though there have been some excellent biographical studies of him by art historians in conjunction with surveys of his work, attempting a full-length biography in the usual sense was not a realistic option.

We are lucky to have a large quantity of his surviving work, often in multiple copies, most of it dated or datable, which gives us some idea of where he was in Europe at what time. From this and from other evidence we know that he was present on occasions for which there is other and plentiful historical data. There exist three of his own handwritten letters, and his name crops up fleetingly in the letters and diaries of others. The Registers in his native Prague and in London, where he spent a large part of his life, provide a little basic evidence of his origins, his marriages, his hopeful petitions to Charles II and his death. In addition, we have brief testimony from three men who knew him personally and from one other who was told about him. It is on their scant and precious sentences that the present story of his life is strung.

Strung, because the material for a conventional documentary account of his life is not there. Hollars religious affiliations are perpetually disputed; the number and destinies of his children are conjectural; his wives are mere names. My solution has been to interleave the straightforwardly factual sections of this book with passages in which I have adopted a number of lost, obscure and therefore imagined voices that are there to convey their own perceptions of Hollar and to shed further light on the world that surrounded him.

These fictionalised passages are not romanticised: I have imagined nothing for my characters that is not either likely or hinted at already in the scraps of evidence we have. Through the medium of apparent fiction is imparted authentic information about the places in which Hollar lived and worked and about the better-documented people of the day whose paths intersected with his. Neither imaginative constructions nor purely factual sections are written to stand on their own, but rather to complement each other.

My other object, apart from the elusive central figure himself, is London. Hollar drew many other places, both within England and on the Continent, but I have chosen to concentrate on the life and times of the city he made peculiarly his own and which he has bequeathed to us.

On a few occasions it has seemed that some details (of the recoverable location of a house, say, or the exact dating of a letter), though absorbing to me, are perhaps more than some readers want: I have therefore put such points in the Notes at the end of this book.

Dwelling as he did on the fringes of more illustrious lives, it has been Hollars fate to be inaccurately represented. For decades, the Dictionary ofNational Biography entry on him has been faulty (though I understand this is being remedied in a new edition) and a rogue reference to him in an otherwise respected work of recent scholarship labels him as Dutch. I am, however, much indebted to several high-quality studies of his life and work (see the Bibliography) and particularly to Richard Penningtons Descriptive Catalogue which, in spite of one or two oddities, is an indispensable work of reference for anyone interested in Hollar today.

Next page