It is almost thirty-five years now since the first edition of The Fields Beneath appeared. Other editions followed, but I was not able to update the work with anything more than a brief note. Not that update is quite the word, for to keep a book of this kind accurate in each current detail noting changes in shops, the enhancement or loss of buildings would require constant, impractical revising and, at another level, would not be desirable anyway. Books of history do not go obviously out of date in the way that some other forms of writing tend to, but nevertheless a book is always a product of its own time, embodying the assumptions, hopes, fears and preoccupations of that time. This Postscript does not attempt to revise my earlier views, but it seems a good moment to take a general look at the way my chosen example of a village engulfed by a great city has continued to evolve over the past generation.

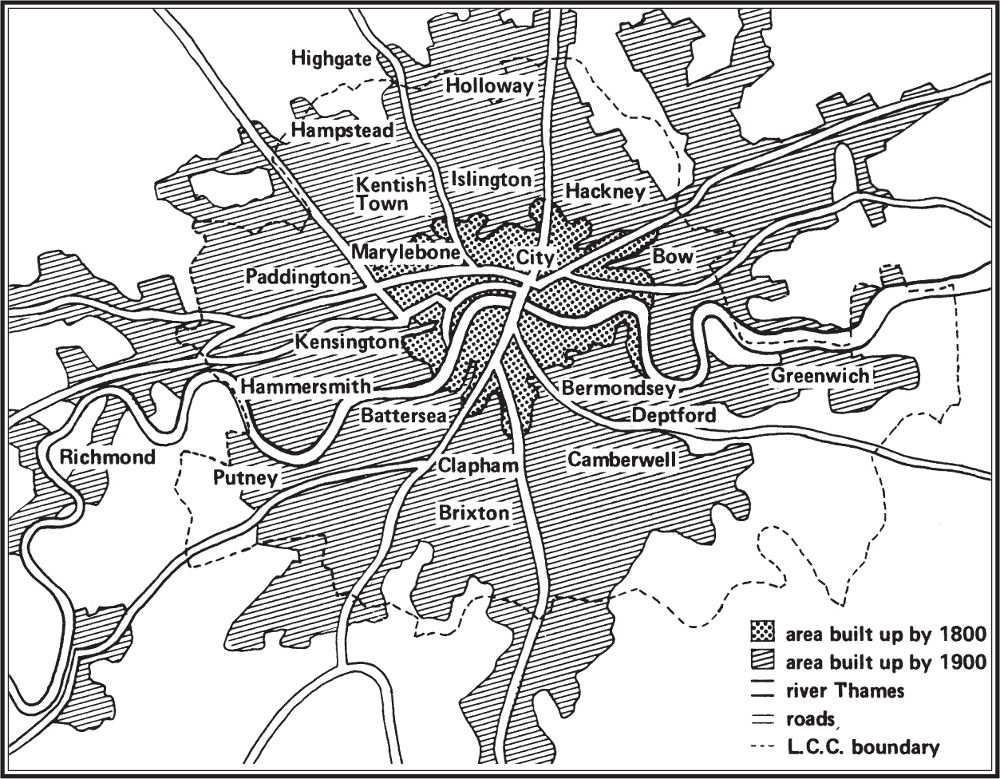

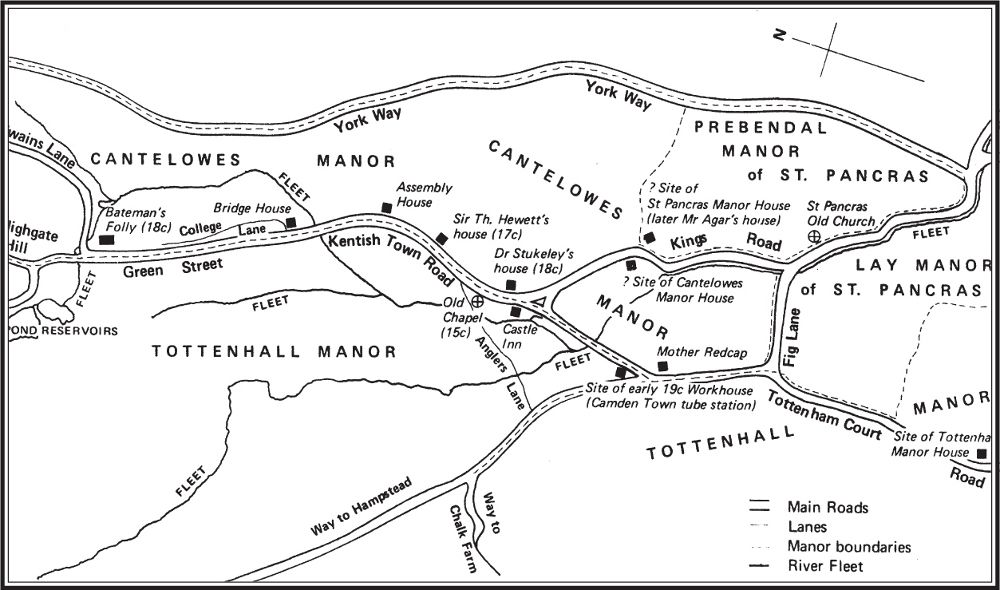

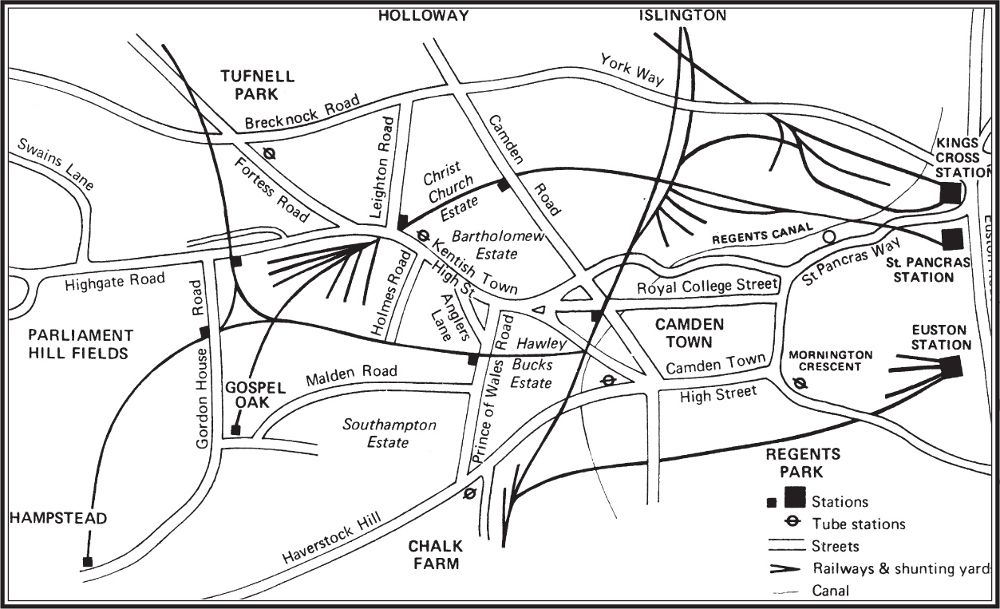

The overall theme of the book is, in any case, change. In the course of sixteen hundred years or so, Kentish Town was transformed from a small settlement beside a track some miles out of London into the busy inner-city district it is today. But this change, however momentous, was sporadic. For centuries nothing much happened, and at one point in the later middle ages the settlement even seems to have declined in size. A minor building boom in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries produced the rural retreat within easy reach of town that was Kentish Towns character throughout the eighteenth and early nineteenth century, though the wind of change began to blow more strongly after the end of the Napoleonic wars. The truly cataclysmic change came in the 1840s, 50s and 60s, when the pastures and market gardens that had been the backland to the High Road were covered inexorably, field after field, with terraces of houses. This was followed by the coming of a mainline railway, which bisected the district and destroyed, for the next hundred years, most of the pretensions it had had to prettiness and gentility. In the space of less than thirty years a sooty townscape was created, as if by a black-hearted fairy. These were essentially the streets that still make up NW5 today.

Because to us past eras are over, fixed and known, we tend to underestimate how traumatic such developments were to people living through them. In the mid-1970s I wrote: To believe that change, and in particular the speed of change, is something peculiar to the twentieth century, is an error, at least where the physical environment is concerned. Except in a few specific places the changes seen by many people living today are as nothing compared with the paroxysms of alteration and despoilation weathered by their great-grandparents. This, in 2011, should read great-great-grandparents, but it remains just as true.

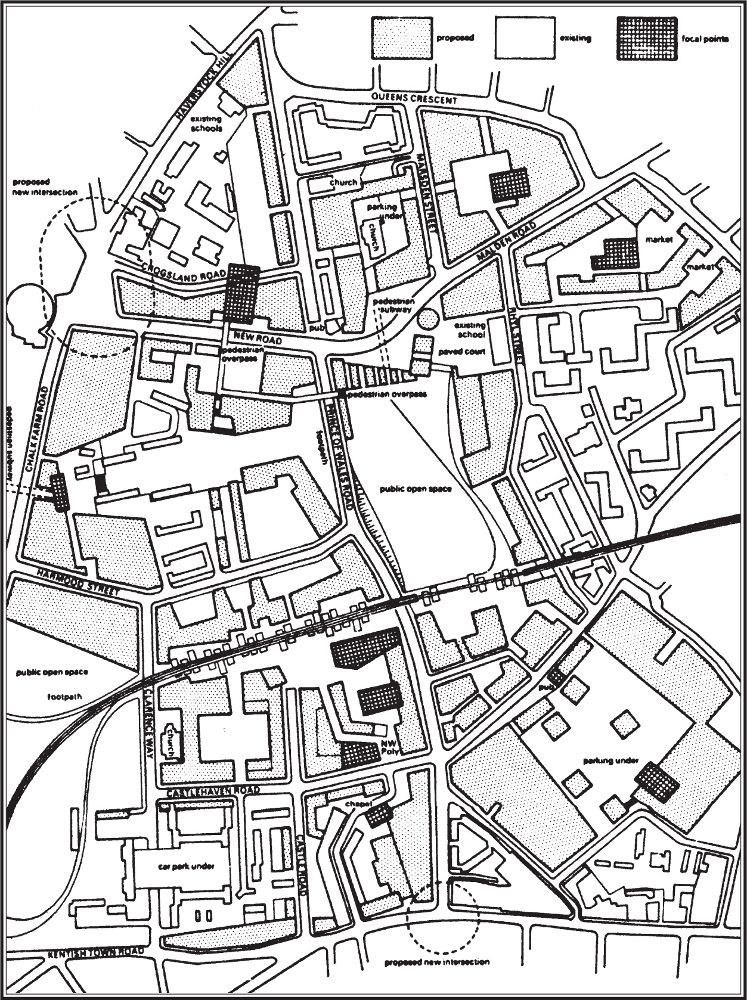

It so happened that, when I was researching and writing The Fields Beneath, the lesser paroxysm of post-war redevelopment had only recently abated. I was thus able to describe this saga of misplaced idealism and Stalinist authoritarianism disguised as democracy while it was still very recent see the books last chapter. But what is significant is that I have no comparable upheaval to report for the period between the late 1970s and today. Just as, by the 1870s, Kentish Town had acquired much the form and social composition that it was to have for the next eighty-odd years, so, after the intervening storm of the late- 1950s and 60s, the place settled down again into very much the one that we still inhabit, more than thirty years on, and shows every sign of continuing for the time being in the same way.

In the 1970s some people feared that by the year 2000 (a then distant, mythic date) areas such as Kentish Town would have deteriorated into urban jungles on the American model, dangerous to cross after dark and full of racial tensions, while others were optimistically convinced that the ever-rising price of property would ensure that Kentish Town in 2000 would be as affluent and exclusive as Chelsea. For more than one reason, I am pleased to report that neither of these predictions has turned out valid. The changes I have to signal are all relatively minor ones, in the scheme of things and in Kentish Towns long and chequered history.

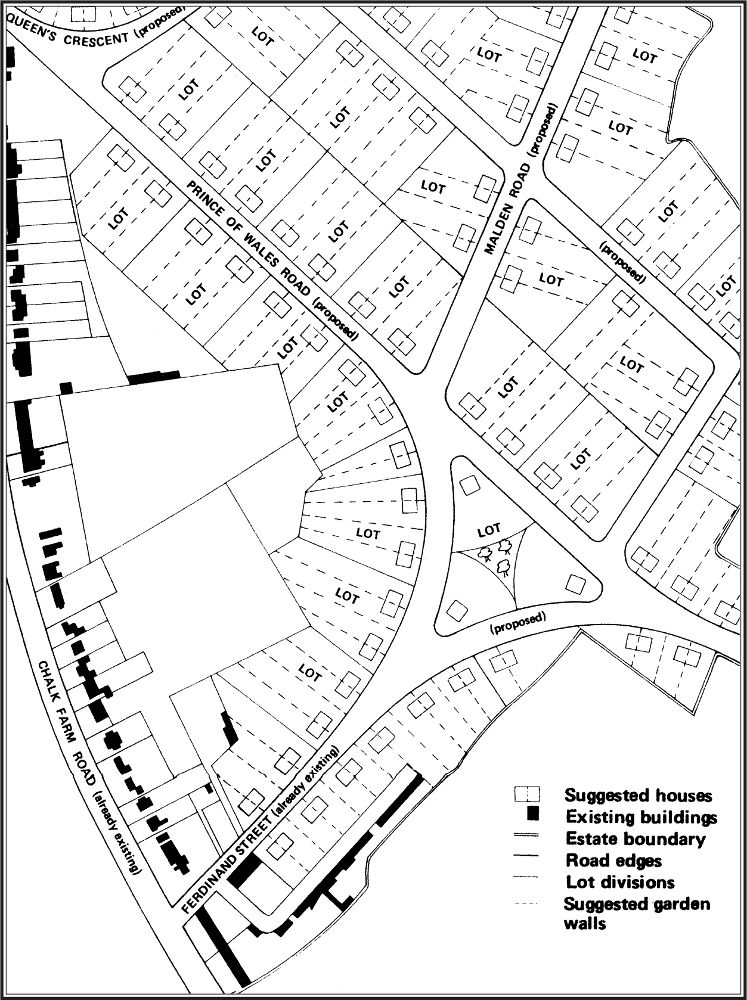

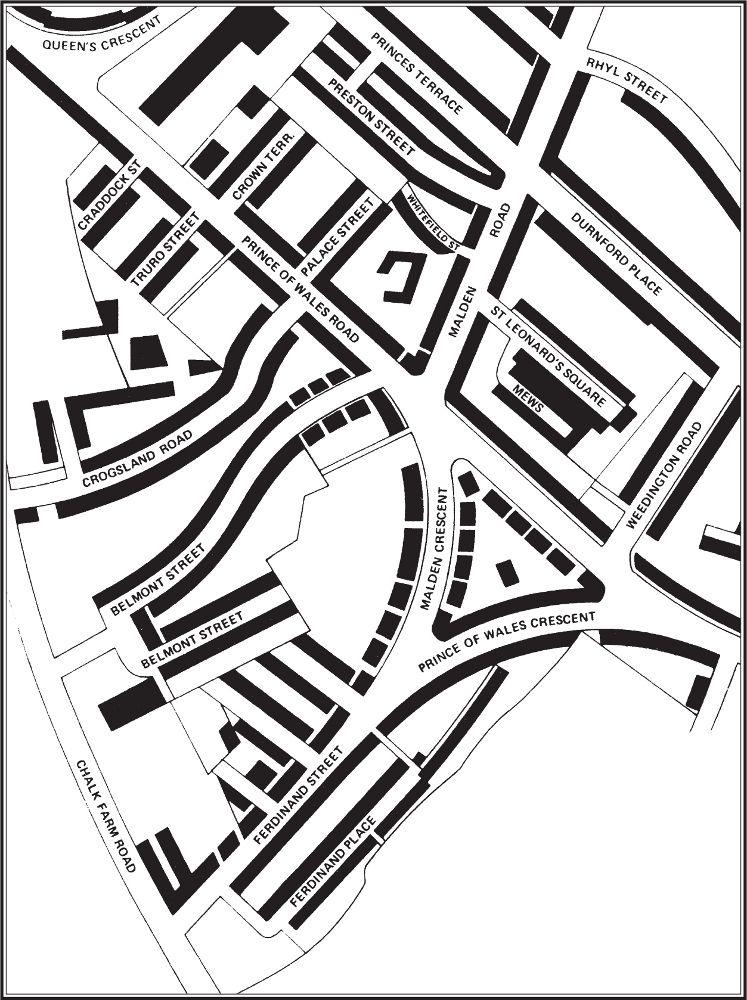

The trends visible in 1977 have simply become more evident. The district has remained remarkably mixed, socially, with inhabitants ranging from the obviously poor to the discreetly wealthy, and only the lower-middle class under-represented. You have to be relatively well-off, today, to buy a Victorian house in one of the areas many pleasant, leafy side streets, and very few of these houses are still in multi-occupation: the old ladies who let lodgings have gone. However, the large amount of housing that remains in local authority hands continues to ensure that the district is hardly in danger of becoming exclusive. But one has to say, too, that the difference between one part of Kentish Town and another, often not far off geographically, has become more marked; and the foreboding that Kentish Town might become parcelled out, into expensively gentrified streets on the one hand and single-class ghetto estates of Council flats on the other, has to some extent come true. The planning-blight that descended upon west Kentish Town in the 1950s and 60s had a permanent effect, and though the partial destruction and rebuilding in the name of improvement in the years that followed was much less extreme than originally intended, it has confirmed west Kentish Towns character as the less desirable side of town. Excepting, of course, places such Kelly Street and the Crimea enclave: these, once narrowly saved from demolition, are now carefully conserved, worlds away in character though not in distance from the ill-designed housing blocks and litter of Malden Road.