Gillian Tindall - The Memory Stick

Here you can read online Gillian Tindall - The Memory Stick full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: Vintage Digital, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Memory Stick

- Author:

- Publisher:Vintage Digital

- Genre:

- Year:2019

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Memory Stick: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Memory Stick" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Memory Stick — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Memory Stick" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

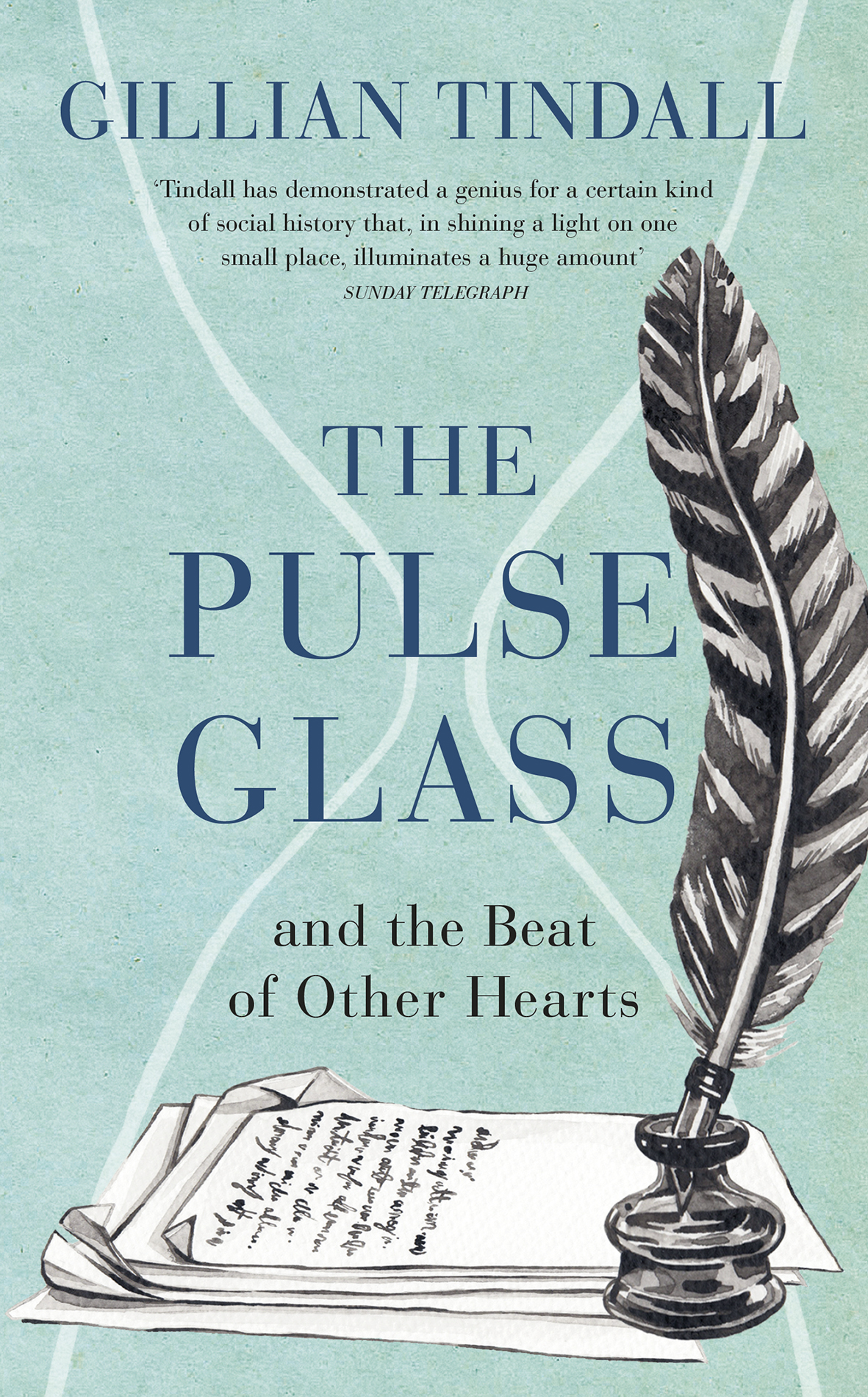

Gillian Tindall is a master of miniaturist history, well known for the quality of her writing and the scrupulousness of her research; she makes a handful of people, a few locations or a dramatic event stand for the much larger picture, as her seminal book The Fields Beneath, approached the history of Kentish Town, London. She has also written on Londons Southbank (The House by the Thames), on southern English counties (Three Houses, Many Lives), and the Left Bank (Footprints in Paris), amongst other locations, as well as biography and prize-winning novels. Her latest book, The Tunnel through Time, traced the history of the Crossrail route, the forthcoming Elizabeth line. She has lived in the same London house for over fifty years.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Fly Away Home

The Intruder

Give Them All My Love

The Fields Beneath: The History of One Village

The Born Exile: George Gissing

City of Gold: The Biography of Bombay

Countries of the Mind: The Meaning of Place to Writers

Clestine: Voices from a French Village

The Journey of Martin Nadaud

The Man Who Drew London: Wenceslaus Hollar in Reality and Imagination

The House by the Thames

Footprints in Paris

Three Houses, Many Lives

The Tunnel Through Time: A New Route for an Old London Journey

This book is dedicated to my husband and lifetime companion, Richard Lansdown

Question put to Prof. Paul M. Cobb of Pennsylvania University:

What is your favourite archive?

Answer: That box you discover in your grandparents attic.

History Today, June 2017

Those who knew

what was going on here

must make way for

those who know little.

And less than little.

And finally as little as nothing.

The End and the Beginning by Wislawa Szymborska

(translated by Joanna Trzeciak)

So the little woolwork picture had gone at last in its own good time During its existence it had given pleasure to a number of people, which is mainly what things are for

Now the possibility of its ever having an effect of any kind upon any human being again seemed gone

A Dog So Small by Philippa Pearce

But when from a long-distant past nothing subsists after the people are dead, after the things are broken and scattered the smell and taste of things remain poised a long time, like souls amid the ruins of all the rest; and bear unfaltering, in the tiny and almost impalpable drop of their essence, the vast structure of recollection.

la Recherche du Temps Perdu by Marcel Proust

On a Good Friday in April, in the second decade of the twenty-first century, I go to sprinkle ashes along the stones, primroses, bluebells and last years leaves of an abandoned railway line in Sussex that has become a path for walkers and cyclists.

Human ashes are flecked pale grey and white, like a large stock of pearl necklaces chopped up and mixed with clean dust. They pour dry and smooth, leaving only the faintest floury residue on the hands. While they are packed tightly into the bag supplied by the crematorium, this concentrated, irreducible residue of an adult human being, these chips of bone, weigh only about six or seven pounds, the weight of a newborn baby.

When this man, who is now ash, was born, some ten days earlier than the expected date, he weighed just over seven pounds. A very cold morning at the start of a winter just after the end of the Second World War, which was to turn into one of the worst winters of the century. A few years later, when we sang at school near Christmas time earth stood hard as iron, water like a stone, it made me think of that winter, which has now receded so far, out of most living memories, that the carol fits it still more closely:

Snow had fallen, snow on snow, sn-oow on sn-oow

In the bleak mid-winter, lo-oong ag-oo

Long ago. In the cold house in Sussex near Ashdown Forest all houses were cold, long ago, unless you were right by the kitchen or sitting-room fire I am fast asleep in my own room. Then, suddenly, I am awake, and someone is standing by my bed:

Youve got a little brother!

Great excitement. I am hustled into my dressing gown. As we cross the landing to my mothers bedroom I encounter a familiar doctor-figure, in black jacket and pin-striped trousers, just leaving. Hello, Mary-Jane! he says. He calls all boys John-Thomas and all girls Mary-Jane. It makes life simpler for him, he says.

My mother is in bed, tucked up, looking quite ordinary, which surprises me rather. Beside her is the long-promised baby, cocooned in a small, woven orange blanket, which I know has been sent by an aunt all the way from Orkney. Such presents were valuable and prized, in 1946.

That blanket survived time and chance, and the disintegration of our home when I was seventeen and the baby boy not yet nine. When I was a young woman I adopted it as a shawl, and later as a wrap for my own son. A generation further on, it was still with me and served to cocoon my first grandson, but somehow between his infancy and the birth of another one four years later it disappeared, perhaps to some other, unknown baby.

Most objects, like all people, disappear in the end. Even in a country as relatively peaceful as the British Isles, which has endured neither invasion nor civil war for several hundred years, there are few possessions more than one hundred and fifty years old, and most are far, far more recent.

Yet already, by the eighteenth century, three hundred years ago, we had in Britain a burgeoning middle class larger than that of any other European country, and replete with possessions. These people, both the well-to-do and the aspirant middling sort, were, by the days of the Hanoverians, doing quite nicely, thank you. Wills, and still more probate inventories, reveal a mass of sheer stuff, all valued and obsessively itemised. The consumerism that would develop in the wake of the industrial revolution and the unprecedented wealth of the Victorian Empire still lay in the future, but, looking from our side of time, signs of its approach were already apparent. Adam Smith, the author of The Wealth of Nations (1776), remarked that even quite modest British homes frequently contained objects brought or copied from the other side of the world, thanks to the energies of the East India, Levant and Hudson Bay Companies. This was at a time when the mainly-rural people of other European countries were still fabricating everything for their own use, with the sole exceptions of iron and salt. British families had Delft plates and English imitations of the same, dresses made of Indian cotton and Kashmir shawls. They had copper pots and pewter ones. People slightly higher up the social scale had silver forks and spoons. They had cloudy mirrors and decorated tea-caddies and miniature writing desks, and books for they could mostly read. The most prosperous had engravings and even portraits in oils, and cloaks lined with fur from the Baltic, lockets and brooches and a great deal of closely guarded silk and lace, and necessary thick-felted wool to protect against time and chance

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Memory Stick»

Look at similar books to The Memory Stick. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Memory Stick and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.