Contents

About the Book

Crossrail, the Elizabeth line, with its spacious, light-filled stations, is simply the latest way of traversing a very old east-west route through what was once countryside to the old City core and out again. Visiting Stepney, Liverpool Street, Farringdon, Tottenham Court Road (alias St Giles-in-the-Fields) and the route along Oxford Street (alias the Way to Oxford and also Tyburn) this richly descriptive book traces the course of many of these historical journeys across time as well as space.

Archaeology disinters layers of actual matter; one may also disinter the lives that walked where many of our streets, however altered in appearance, still run today. These people spoke the names of ancient farms, manors and slums that now belong to our squares and tube stations. They endured the cycle of the seasons as we do; they ate, drank, laughed, worked, prayed, despaired and hoped in what are essentially the same spaces we occupy today. As The Tunnel Through Time expertly shows, destruction and renewal are a constant rhythm in the citys story.

About the Author

Gillian Tindall is a master of miniaturist history, well known for the quality of her writing and the scrupulousness of her research; she makes a handful of people, a few locations or a dramatic event stand for the much larger picture, as her seminal book The Fields Beneath, approached the history of Kentish Town, London. She has also written on London's Southbank (The House by the Thames), on southern English counties (Three Houses, Many Lives), and the Left Bank (Footprints in Paris), amongst other locations, as well as biography and prize-winning novels. She has lived in the same London house for over fifty years.

By the same author

Fly Away Home

The Intruder

Give Them All My Love

The Fields Beneath: The History of One Village

The Born Exile: George Gissing

City of Gold: The Biography of Bombay

Countries of the Mind: The Meaning of Place to Writers

Clestine: Voices from a French Village

The Journey of Martin Nadaud

The Man Who Drew London: Wenceslaus Hollar in Reality and Imagination

The House by the Thames

Footprints in Paris

Three Houses, Many Lives

List of Maps

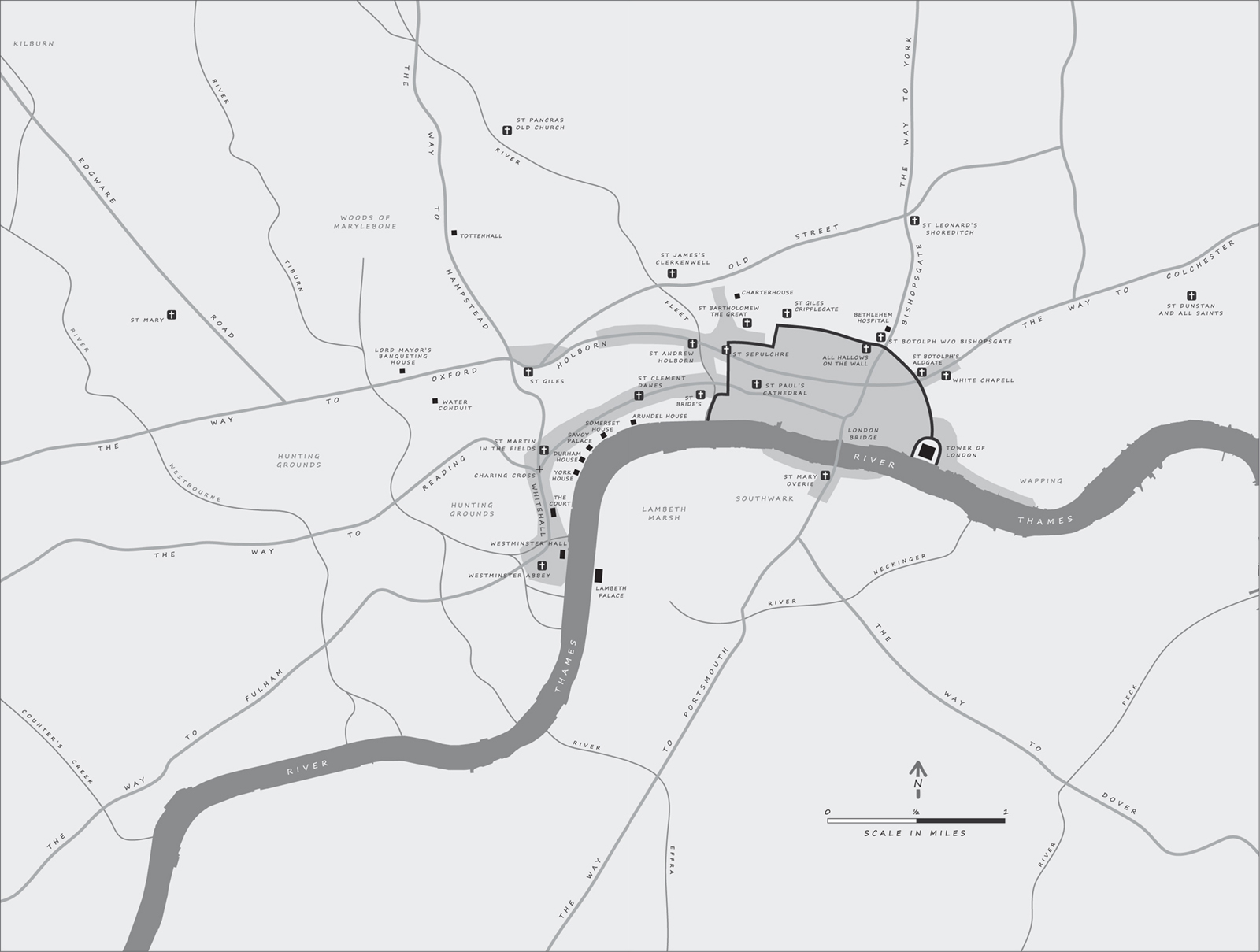

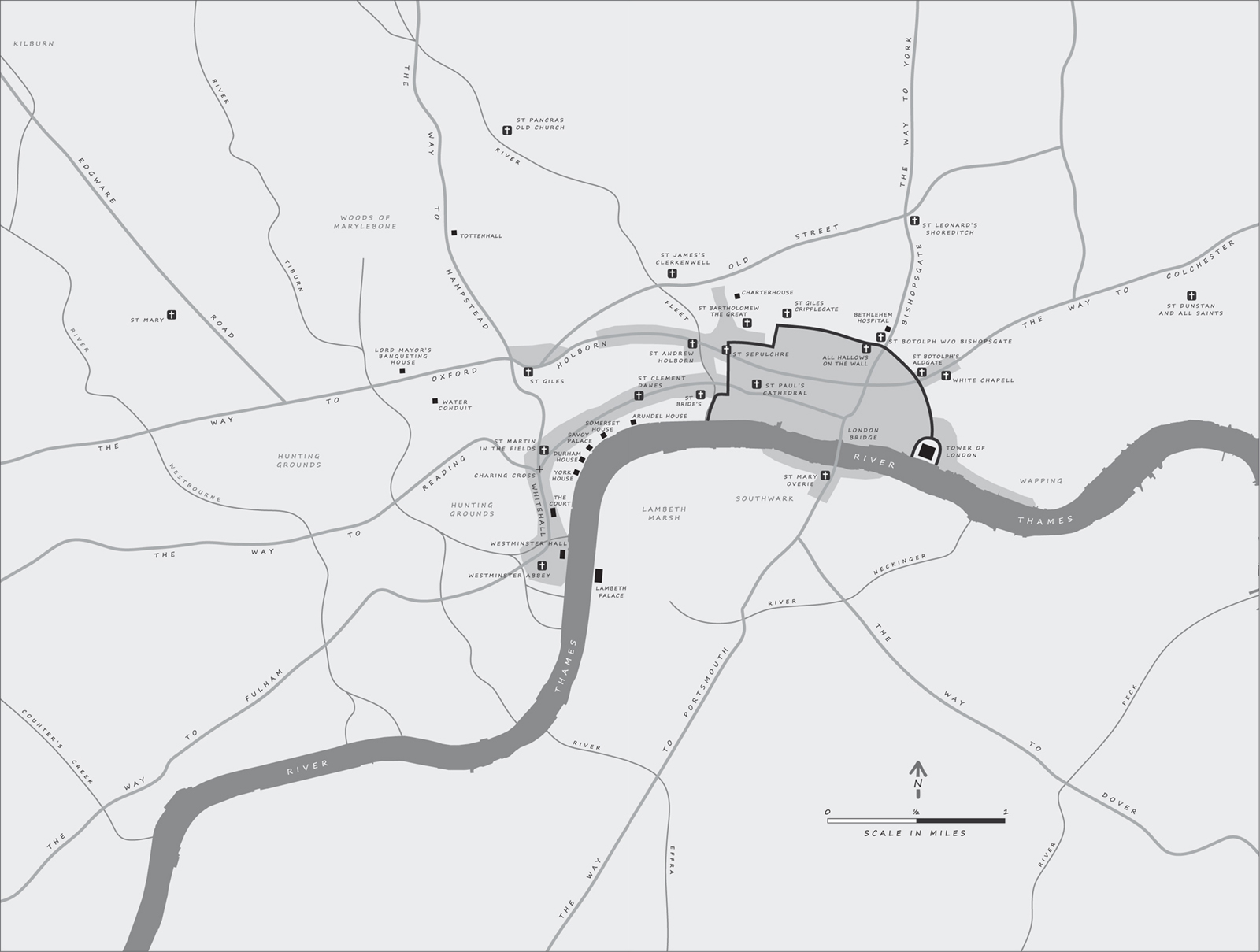

| London, c. 1550 |

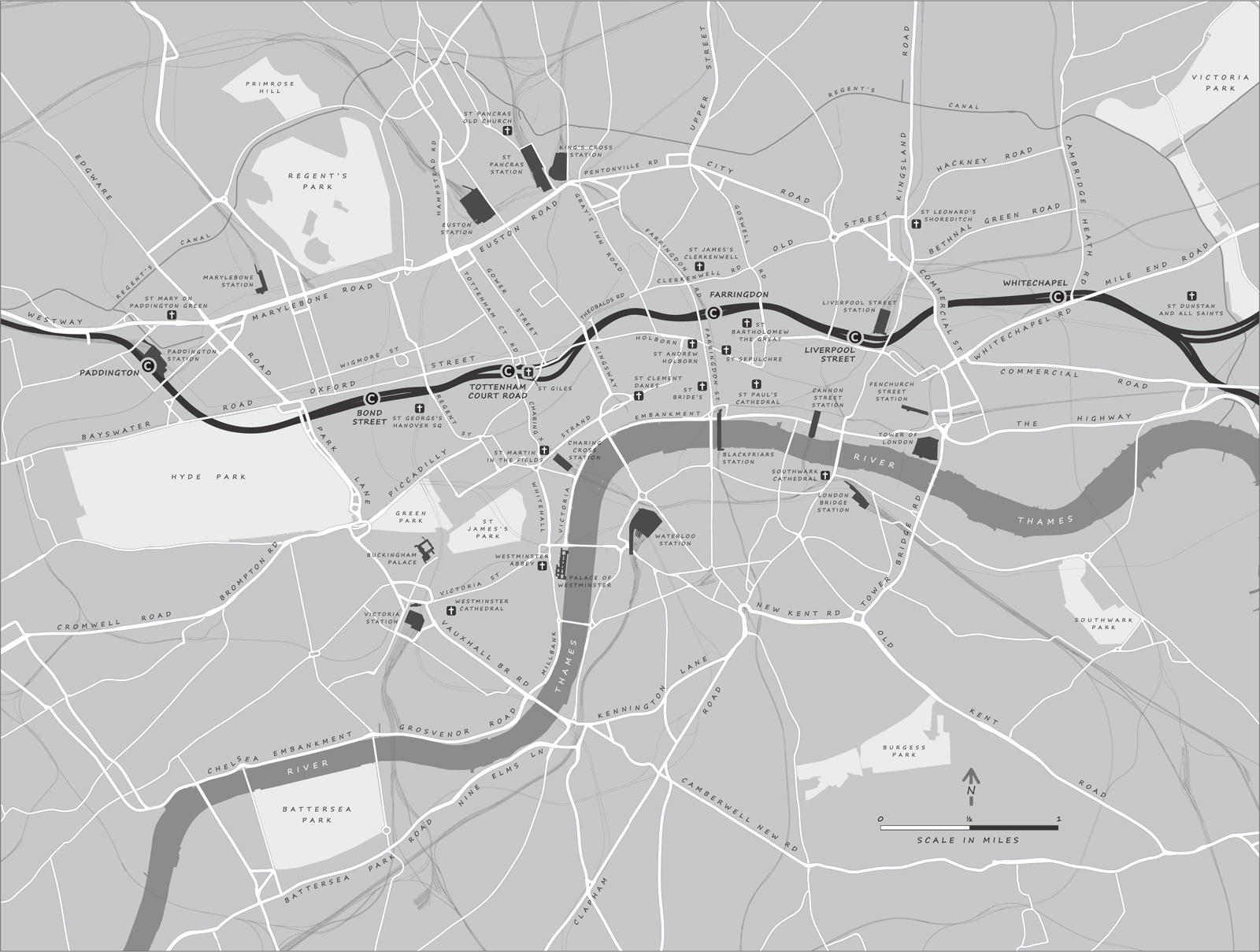

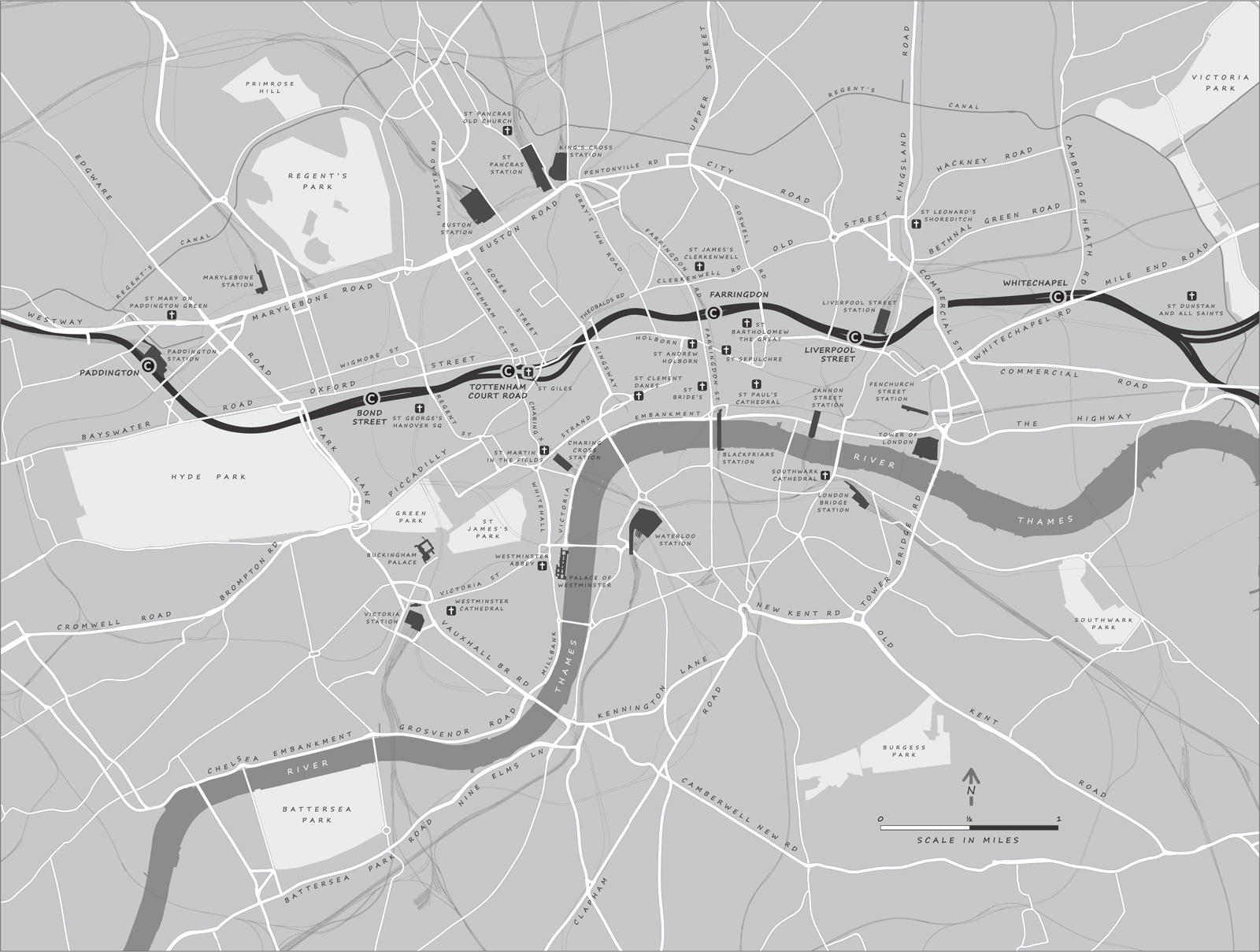

| London today |

| St Giles-in-the-Fields, c. 1550 |

| St Giles/Tottenham Court Road district today |

| The way north from the Bishops Gate, c. 1550 |

| Bishopsgate/Liverpool Street/Shoreditch district today |

| Stepney, c. 1710 |

| Farringdon and Holborn, c. 1550 |

| Farringdon and Holborn today |

| Stepney today |

| St Giles and Seven Dials district, c. 1840 |

| The way to Oxford through the Tyburn crossroads, c. 1750 |

| Oxford Street, Marble Arch and Marylebone districts today |

London, c. 1550. The significantly built-up area is shown in darker grey

London today, with the Crossrail route

We have not an abiding city, but we seek after the city that is to come.

From Pauls Epistle to the Hebrews, chapter 13, verse 14

Remembering how generations of men and women come and go, and how swiftly the lingering memories of their lives follow them, one cannot help looking with some degree of interest upon the old houses in which they were born, lived, and died. We fancy that the walls which echoed their first wailing cry, and caught, in the hushed, awful silence, the sound of their last breath, deaf, dumb and blind though they are, must cherish remembrance of such daily doings; of loving, hating, rejoicing and grieving, hoping and fearing; of hard struggles and terrible failures, or glorious victories.

From an editorial in The Builder, 11 September 1875

Yerkes, the projector of the new Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead electric underground, said to me that in spite of the opposition which he meets at every turn he proposes to go through with it... He predicted to me that a generation hence London will be completely transformed; that people will think nothing of living twenty or more miles from town, owing to electrified trains. He also thinks that the horse omnibus is doomed. Twenty years hence, he says, there will be no horse omnibuses in London. Although he is a very shrewd man, I think he is a good deal of a dreamer.

From R. D. Blumenfelds R.D.B.s Diary, 6 October 1900

These works, like all alterations and repairs, will give employment to many, and be a nuisance to others, as long as they are being constructed; but when the mess is cleared up, and the new channels are thrown open, a sense of comfort and relief will be felt throughout the vast general traffic of London.

The concluding words of John Hollingsheads

Underground London, 1862

INTRODUCTION

The new Crossrail underground line, which has been built across central London even as I have been writing this account, is, for the greater part, invisible. It is the biggest building project in Europe today, yet surface evidence for it is limited to a small number of deeply excavated sites that have opened up in the heart of London like bubbling geyser holes in a volcanic region. When completed, the new long-distance line, re-baptised the Elizabeth line, is designed to carry passengers from areas outside London to key points in the City and the West End, bypassing intermediate inner-London stops. The great scheme has been on planners desks for several decades, through propitious and unpropitious seasons, but by 2012 construction was well under way and on time, with tunnelling and earth-shifting machines moving very slowly but inexorably, like mythic underground monsters, from separate directions to their final meeting point beneath Farringdon on the western edge of the City.

Yet as a route tunnelled out by machines boring deep under central London, Crossrail is not essentially different in kind from the other tube lines, which began to be constructed in the final years of the nineteenth century. In the Edwardian era, when money for public works was easily found, the popular journalist George R. Simms wrote:

To the engineer of the tube railway, as to the passengers who travel through it, the buildings overhead are a matter of supreme indifference. Eighty or a hundred feet beneath the surface, under the foundations of the houses, the bed of the river, the gas and water pipes, and the older underground railways, he worms his way through the earth, leaving a section of iron tube behind him at every yard of his advance.

That remains as true today, and the photograph that accompanied this article, of a great, round tunnelling shield attended by workmen with moustaches and pickaxes, depicts essentially the same technology that is being used for Crossrail.