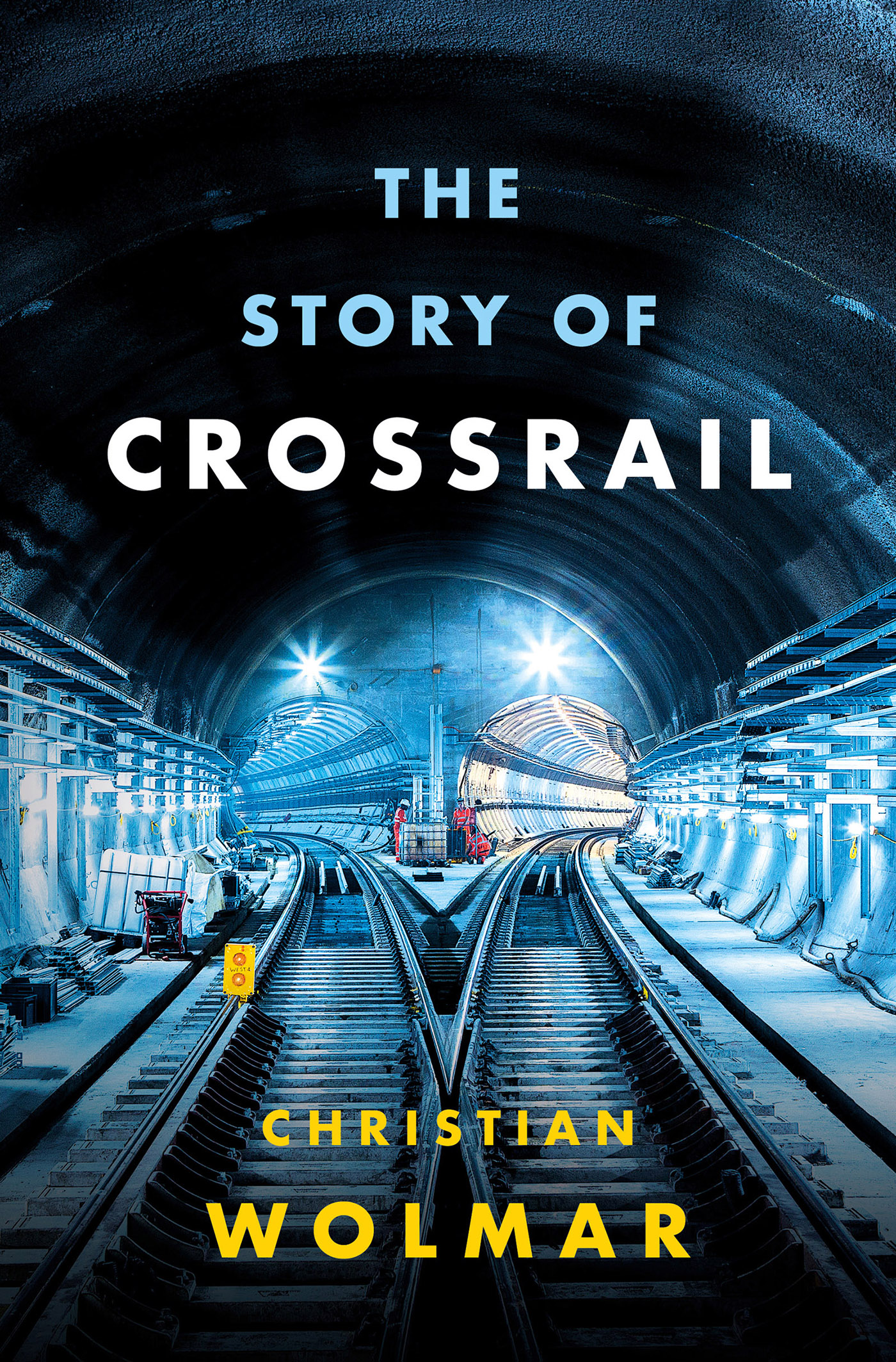

THE STORY OF CROSSRAIL

Christian Wolmar

AN APOLLO BOOK

www.headofzeus.com

The story of an engineering marvel of the twenty-first century, from Britains bestselling railway writer.

In autumn 2019, Europes biggest infrastructure project a state-of-the-art cross-London railway will finally come to fruition. From Reading and Heathrow in the west, the Elizabeth line will extend to Shenfield and Abbey Wood in the east, including 42 kilometres of new tunnels dug under central London.

Crossrail, first conceived just after the Second World War in the era of Attlee and Churchill, has cost more than 15bn and is expected to serve 200 million passengers annually. The author sets out the complex and highly political reasons for Crossrails lengthy gestation, tracing the troubled progress of the concept from the rejection of the first Crossrail bill in the 1990s through the tortuous parliamentary processes that led to the passing of the Crossrail Act of 2008. He also recounts in detail the construction of this astonishing new railway, describing how immense tunnel boring machines cut through a subterranean world of rock and mud with unparalleled accuracy that ensured none of the buildings overhead were affected.

A shrewdly incisive observer of postwar transport policy, Wolmar pays due credit to the remarkable achievement of Crossrail, while analysing in cleareyed fashion the many setbacks it encountered en route to completion.

Contents

Dedicated to my grandchildren and step-grandchildren, all boys, who seem, so far, to love trains Alfie, Luka, Quinn and Louie. May they be travelling on Crossrail in the twenty-second century!

Writing this book has been a labour of love. I might have been sceptical of the Crossrail concept when I first wrote about it almost thirty years ago and the story was exclusively about money and politics. It seemed a rather banal concept, another tunnel under London like the Tube lines which have been part of my life, as I am a Londoner, since my childhood.

However, all the difficulties and faults with the project cannot take away from the fact that Crossrail will be a railway that Londoners will undoubtedly learn to admire and even to love. It is everything that a modern railway should be and its grandeur will put it in the same category as the Moscow Metro or the great stations built during the height of the railway age in cities across the world. I hope my book conveys this sense of excitement and achievement.

The first Crossrail

Travelling between east and west London has always been difficult. While northsouth journeys became much easier in the nineteenth century as more bridges were built and a couple of Underground lines crossed the river, the possibilities for eastwest travel have always been limited because the sinuous path of the River Thames limits the potential for direct routes that avoid river crossings. Going along the embankment necessitates travelling a much greater distance because of the shape of the river and therefore north of the Thames there is only one direct alignment, the old A40, Shepherds Bush to Lancaster Gate. Here, there is a spur along Sussex Gardens towards Marylebone Road, which offers a more circuitous route to the City, while the main route continues along Oxford Street and High Holborn to Bank. From the east, the two main routes, Commercial and Whitechapel Roads (the A11 and the A13), meet at Aldgate, where chaos ensues for those wishing to push further west.

As a result of this geography, the road into London from the west, the Roman Via Tribantia, was the most lucrative of the old turnpikes. In the mid-eighteenth century the tollgate at Tyburn now Marble Arch charged 10d for a carriage with two horses, 4d for a horseman and 2d for twenty pigs. A toll at Notting Hill charged 4d for anyone who used it. For eastbound travellers entering London there was effectively no alternative to using these gates and this remained largely the case throughout the first half of the nineteenth century.

The expansion of all modes of transport across London in the nineteenth century, including the revolutionary concept of building underground railways, was made necessary by the scale of Londons growth during this period. From a relatively well-contained space encompassing much of what is Zone 1 of its transport system today (basically the area inside the Circle Line), London became the worlds first megalopolis thanks to its place at the centre of a burgeoning colonial empire from which it gained extensive benefits. On its eastwest axis, unconstrained by the barrier of a river, London in 1801 stretched for five miles and had a population of just under a million. By the end of the century it was seventeen miles wide with a population of more than 6.5 million. It was by far the biggest city in the world and its position at the heart of the empire ensured it became a magnet for the affluent, the ambitious and the footloose.

This extraordinarily rapid expansion stimulated the establishment of successive new transport systems to accommodate the growing number of people prepared to settle further and further outside the centre in order to find decent housing at affordable prices: new roads, omnibuses, trams (initially horse-drawn and later electric), the Metropolitan Railway and then, by the end of the century, deep Tube lines. Thanks to the constraints of the road system, it was on the eastwest axis that many of these nineteenth-century transport initiatives were first introduced. It is not surprising, therefore, that the very paths they followed correspond to parts of the Crossrail route and the places they served are now the site of several of the lines stations.

The omnibus, Londons first genuine public transport system, made its debut, as would the Metropolitan Railway a generation later, between Paddington and the City of London. The inaugural omnibus service, operated by George Shillibeer, an enterprising Bloomsbury mourning-coach builder with business connections in Paris (where such services were already well established), ran on that route in July 1829. His omnibuses, drawn by two horses, carried twenty-two people, thirteen of whom could be accommodated inside the stagecoach, protected from the elements, with the rest seated on top, where fares were lower. At around 6d even for the top deck, these fares were prohibitive for most Londoners.

The omnibus service was initially aimed at the capitals middle classes, but the need for faster transport developed so rapidly that within a few years omnibuses were serving all the major thoroughfares in London and carrying an impressive 200,000 passengers daily. These buses were the genesis of Londons mass-transport system, but the inefficiency and high cost of horse-drawn transport, as well as the increasing congestion on the capitals main arteries, ensured that omnibuses could never, alone, meet the transport needs of the capitals growing population. In the mid-nineteenth century, as London filled up and expanded dramatically north of the river, none of the forms of transport in the capital was particularly enticing. Although the railways soon expanded outwards from the large termini built on all four compass points, there was little effort to provide for the onward journeys of the increasing number of passengers arriving in London or for access to these new stations from other parts of the capital. Apart from walking, still the only option for most people including many in work, and the omnibuses, there were Hackney cabs, the horse-drawn forerunners of taxis, which, at 8d per mile were expensive and consequently out of reach of most of the population. London was therefore in need of a transport revolution.