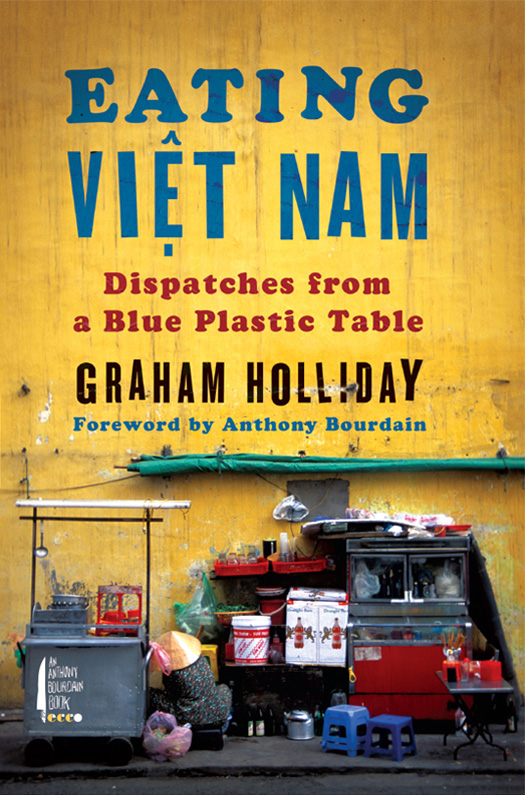

for noodle girl

and the toad

CONTENTS

Guide

FOREWORD

BY ANTHONY BOURDAIN

Vit Nam owns me. From my first visit, I was helpless to resist.

Just a few months previous, Id been resigned to the certainty that I would never see Vit Nam; that my dreams of Graham Greene Land, that faraway place I only knew from childhood news reports, books, and films would have to wait for another life. This life, I was sure, would finish in close proximity to a Manhattan deep fryer.

So, simply finding myself there, finally, outside the legendary Continental Hotel in Si Gn, smelling Vit Nam, hearing it, the high roar of thousands of motorbikes, I was overcome with gratitude and disbelief. Jet-lagged (back when I still got jet lag) and deranged by anti-malarial meds, I staggered happily through the heat to the places Id read about in the great nonfiction accounts of the French and American wartime years: the Majestic, the rooftop at the Rex, and of course, the very hotel where I was staying. I ate steaming, spicy bowls of ph on the street, and crispy fried quails, and was delightfully overwhelmed by the smells and flavors of Bn Thnh market. I ventured out into the Mekong Delta, where I got savagely drunk with an extended family of former Vit Cng. I explored the islands and floating markets off Nha Trang, had many adventures, and made lasting friends.

And I changed.

My attitude changed, of course. Your eyes cant help but open when you traveland just to see the places Id read so much about was surely life-changing. But something else changedon an almost cellular level, as if my very tissues had been penetrated by the smells and atmosphere of Vit Nam, that heavy air, thick with odors of jackfruit, durian, fresh flowers, raw chicken, diesel fuel, incense. Vit Nam is a country of proud cooks and passionate eaters. And, after experiencing the spicy morning soups of Si Gn, the notion of ever settling for a bland Western-style breakfast again was unthinkable.

I was hooked. I wanted more. I needed more. I left Vit Nam that first time determined to do whatever was necessary to keep coming backeven if that involved something as undistinguished as making television.

I have since visited the country many times, always with a television crew. Unsurprisingly, the people I work with have always come to feel the same way about the place as I do.

In the preproduction phase of one of those shows, I came across a wonderfully unusual, deeply authoritative food blog called noodlepie, by a British expat named Graham Holliday.

For reasons I would only later come to understand, this man had chosen to exhaustively photograph, write about, explain, and appreciate the kind of street food vendors I loved but still knew relatively little about.

No one I was aware of, anywhere, owned his territory like Holliday. He explained everyday, working-class Vietnamese food from the point of view of an enthusiast: insider enough to have access to, and understanding of, the facts, but outsider enough to thrill at the newness and strangeness of it all.

Hollidays knowledge of the street food landscape in H Ni and Si Gn was breathtaking. He went deep in his search for every bn ch and ph vendor in H Ni, each purveyor of bnh m in Si Gn, soliciting suggestions from xe m drivers, students in the English classes he taught, neighbors and strangers. Hed follow each lead, or stop in at whatever stall or shop caught his eye in his exhaustive urban travels, and report back thoughtfully, without bias, condescension, or clich.

In preparing to visit, my colleagues and I began to piggyback shamelessly on Hollidays extraordinary body of work. In Si Gn, his careful-yet-joyous research sent us down an alley to Mrs. Thanh His snail stall. We heeded his advice and found the masterful crepe cook at 46A Dinh Cong Trang, whose beloved ancient pan yields the citys best banh xeo.

I was a huge fan of his blog for as long as Graham lived in Vit Nam, and felt, always, that there was an important book there. A few years later, when Dan Halpern at Ecco Press, in his wisdom, gave me my own publishing imprint, I saw an opportunity to help make that book happen. When asked who in the whole wide world had a story and a voice Id like to publish, Graham Holliday was one of the first people I thought of.

What would it be like to move to Vit Nam? To actually live there? To both live the dreamand deal with a very steep learning curvea stranger in a strange, yet wonderful, wonderful land? What would that be like? Surely many of us have wondered about that. I know I have.

Eating Vit Nam provides an excellent account of what that might be like. It takes a special kind of person to move to a country as complicatedwith as complicated a historyas Vit Nam, and to let things happen, to let things in, to let it all wash over you and through you. It takes an even more special person to describe the experience so richly and affectionately, clear-eyedand yet always with heart.

This isand will remainan essential account for anyone considering travel to Vit Nam. But it should be a deeply rewarding read as well for those who wont be getting that opportunity anytime soon. A solid jumping-off point for the imagination. The beginning of a dream.

Because, as I found out, the dream comes first.

A S THE PIGS UTERUS LANDED ON THE BLUE PLASTIC table in front of me, I knew Id made a mistake.

Not that I understood that the slab of shiny pinkness plonked atop a tangle of green herbs was a farm animals womb at first. I was certain of only two things:

1. It didnt look good.

2. I was expected to eat it.

It was a late summers evening in 1997. The air hung like a damp, hot curtain. Mine was the sole white face jammed in among hundreds of cackling, beer-soaked Vietnamese men seated at a grubby intersection on Tng Bt H Street in the south of H Ni, the capital of Vit Nam.

I like to come here after work to relax, said Ngha, an IT consultant and my student. I taught English at the first foreign-run English-language school in the capital. He wore a white shirt, white socks, black trousers, and black shoes. The memory of teenage acne streaked across the forty-year-olds face.

Ngha bent over the table to inspect the recent arrival and seemed pleased by what he saw. I was not pleased. Dinners arrival had sent my appetite hightailing it down the street. I was panicked, distressed, and chained by good manners to the dinner table.

Using a pair of wooden chopsticks, Ngha picked up a slice of uterus and placed the morsel between his teeth. He left his mouth open as he masticated. Like a washing machine warming up, he churned the offal this way and that, tossing it from incisor to molar and back again. He looked up at me. The crescent moon of his chomping mouth radiated approval.

Its good. Good snack food. Good for drinking beer. Try some.