A new life awaits you in the off-world colonies. The chance to begin again in a golden land of opportunity and adventure.

Blade Runner

MARCH 26, 2015

I was sitting in a basement bar below a nondescript alley, off a nondescript side street, connected to a nondescript eight-lane highway in the downtown Jongno district of Seoul. There were six tables placed at angles, full of customers and illuminated by candlelight. I was with a friend. Some food arrived and he leaned forward. Wax dripped upon the table, his face glowed ghoulish in the gloom. He had a look almost of pride.

This, he said, admiring the food that separated us, is the future.

I looked at the grilled, disc-shaped object on the plate between us.

Its a pizza, I said.

No, he said, its the future of Korean food.

Twenty years had passed since Id last seen Andy Salmon in this city; age now creased us and gray tickled our forelocks. Like me, he was British. We had both lived in Seoul back then, but Id left and hed stayed. He used to be a restaurant critic; these days he was a writer, journalist, and TV presenter.

Try it, he said. It sounded like a dare.

Id never seen anything good come out of South Korea in the shape of a pizza. And what gazed up at me from the plate at Bar Sanchez that night didnt look like it was going to change that. I took a bite. The crust was thin, and there was something odd there, something foreign to any pizza Id ever known. Andy caught my flinch.

What does it remind you of? he asked.

It wasnt unpleasant, but it was savory and also somewhat sweet. It was like no pizza I had ever had a relationship with. It wasnt pizza, it was some kind of hermaphroditic food form.

Its sweet, I said, putting the half-eaten slice back down on the plate. Thats no pizza. I shook my head. I couldnt place what it reminded me of. No idea, I said. Its an odd one.

Fruit cake, said Andy. A dessert pizza with a whiff of fruit cake.

He leaned back in his chair and waved a hand toward the bar.

This Sanchez, he said, Hes an absolute genius.

Bar Sanchez was a modish crevice in downtown Seoul. Sanchez worked behind the small bar, and despite his name, Sanchez was Korean. He had one portable burner upon which he cooked and one person to help him prepare and serve. What this young Korean man was creating, Andy told me, was nouveau Korean food.

Im telling you, Andy said, plucking a slice from the plate, repeating himself, this is it. This is the future of Korean food.

My first night back in Korea with my oldest friend in Koreaa former restaurant reviewer, food guidebook writer, a man married to a recognized Korean food expert and chefand hed presented me with something he called the future, but which to me looked like a mistake, and certainly not identifiable as Korean.

I t was in 1994, midway along the noodle aisle of Pats Chung Ying Chinese Supermarket on Edinburghs Leith Walk, that I first became acquainted with Korean food.

At best, the one-dollar plastic vessel staring back at me from the dustier end of the sell-by date expired shelf was on life support. At worst, it was en route to being read its last rites at the local landfill.

Fate, if you believe in such things, comes in many forms. In my case, it arrived in the guise of a four-foot-tall Chinese grandmother with a tight, dyed-black perm and an insistent right elbow.

In hot pursuit of a half-price maxi soy sauce vat, this diminutive old lady knocked me sideways, sending herself clattering into the cheap shelf and much of Edinburghs cast-off Asian edibles crashing to the floor.

Oyster sauce, pickles, fish sauce, and rice vinegar all made a leap for freedom, only to meet their sticky, broken end on the supermarket floor. I watched the glass, pickles, and sauces smash around me as a single bottle floated from its perch and dropped into my shopping basket. It lay there, cap covered in dust, nestled like an orphaned child in a blanket of instant noodles and shrimp crackers.

Clearly, it was meant to be. I bought it.

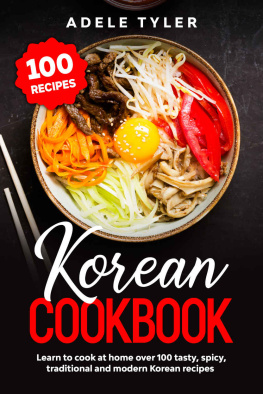

Back home, I sat in the kitchen and eyed this mysterious new arrival. Three words on the label gawped back at me: Korean Bulgogi Marinade. Bulgogi sounded like a device youd put in a babys mouth to shut it upit didnt sound like food. I knew nothing of Korean food, and I was ignorant of how it should sound. However, I had come across marinades. Simple enough in theory: slop contents over dead animal, leave to fester, apply fire, serve when ready. Easy.

So thats what I did. With slices of cow.

I ate it quickly. The flavors of the beefsweet, sesame oil, soy sauce, and garlicunnerved my taste buds. Upon finishing, I swayed, slightly stunned, and surveyed the aftermath.

The empty plate glistened. Dark pathways of soy wiped their way across the secondhand porcelain. My head wrangled with the mass of mental rubble this meal had just bulldozed to one side of my brain. Within the space of a few short minutes, an unexpectedly desirable part of the culinary world had opened up a promising development in the part of my mind that prospected for tasty new real estate.

Two years later, having trained as a teacher, I relocated to the country from whence the dark, saucy genie had come. Ostensibly, I moved for work. In reality, I went to see what other Korean things I could eat. I ended up living and eating my way around the Hermit Kingdom for the better part of two years.

It was in the midnineties, while teaching at a state school in the southwest of the country, that I fell in love with South Korea and with Korean food. With the bubbling cauldrons and the pepper-and-garlic-steam-filled orange tents, called pojangmacha, that appeared on the streets and in parking lots from early evening to early morning. The Korean food I devoured daily detonated in my mouth like a pop art exhibition. It had never heard of cheese and would have grown nauseous at the thought of fruit cake.

When I first arrived in Korea in 1996, I had eaten only that self-made bulgogi and a chicken and potatoes dish called dak dori tang ( ) cooked by a Korean student of mine. There were no Korean restaurants where I lived in England. I arrived ignorant, and during a two-week induction in the central city of Cheongju, I went in search of the two dishes I knew. I popped my head inside several small eateries and in pathetic Korean said, timidly, Dak dori tang?

That was how I ended up inside an old ladys living room, surrounded by dark brown wooden furniture, family portraits, a large, loudly ticking clock, and a TV. The woman slid a thin silk cushion my way and gestured for me to sit down. Looking back, I dont think she was running a restaurant businessshe had just taken pity on me. She headed into the pantry and left me alone, facing the TV, tuned to the news in Korean. What she came out with ten minutes later was