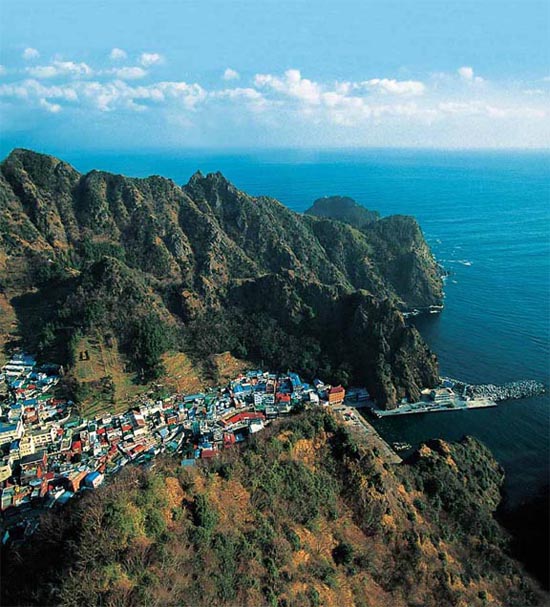

LEFT : A fishing village on Ulleungdo Island, prized for its seasonal fish and cuttlefish. The quality of their seafood is so fresh and well known that it is exported to countries such as Japan and the US.

Food in Korea

Geography, climate and history have all shaped Korea's distinctive cuisine

The Korean peninsula juts out like a spur from the Asian mainland, just below Manchuria in northeastern China and eastern Siberia. Approximately the size of the United Kingdom, it stretches 620 miles (1,000 kilometers) north to south, but is only 135 miles (216 kilometers) east to west at its narrowest point. To the west lies the Yellow Sea and China; to the east the East Sea and Japan. Scattered off the jagged coastline are some 3,000 islands.

Apart from the encircling sea, Korea is a land of mountains. An enduring image of this Land of Morning Calm, as it has become known, is of wave upon wave of blue mountains, their peaks rising through the morning mist. Only 20 percent of the country consists of arable land, and of this, a large proportion is represented by the rice-growing Honam plain in southwest Korea. The east coast, ribbed by the magnificent Diamond Mountains, falls abruptly to the East Sea. The west coast is riddled with shallow, narrow inlets that experience large tidal changes. Between these coasts the peninsula is ribboned with swift-flowing rivers originating in the mountains.

In addition to water, the country is rich in forests. An extensive reforestation program began after the Korean War and now the mountain parks are full of juniper, bamboo, willow, red maples, and flowering fruit and nut trees such as apricot, pear, peach, plum, cherry, persimmon, chestnut, walnut, gingko and pine nut. Autumn in the Sorak mountains off the east coast, or spring at Kyongju, ancient capital of unified Korea, brings a marvel of foliage in varying hues.

Korea has four distinct seasons: spring and autumn are temperate, winter and summer verge on the extremes. Winter is particularly cold, with temperatures dropping to 24F (-5C) or less, and often lasts from November until late March. This climate, in combination with the mountainous interior, has given Koreans an appetite for hearty, stimulating foodmeats and soups are cooked with chilies, garlic, ginseng, and many medicinal vegetables, berries and nutswhich helps to keep out the cold and produce energy. At the same time, the four seasons have guaranteed the Koreans a steady flow of seasonal produce. The lowland fields provide excellent grains and vegetables, while the uplands grow wild and cultivated mushrooms, roots and greens. The surrounding seas produce a host of fish, seafood, seaweed and crustaceans. However, it is the sense of food as medicine and long-term protection that has governed the evolution of the Korean diet. Even raw fish sashimi is given extra vitality by being seasoned with red chili. Most meals are served with a gruel or a soup, as well as the ubiquitous, fortifying kimchi and a range of vegetarian side dishes collectively known as namul, which are delicately seasoned with soy, sesame and garlic.

Koreans often look to herbal remedies for illnesses, the result of their grounding in Chinese medical belief about the yin-yang balance of the body and the cooling-warming properties of certain foods. The most common medicinal foods used in cooking are dried persimmon, dried red dates, pine seeds, chestnut, gingko, tangerine and ginseng. The saponin in garlic, which Koreans often eat raw, wrapped in a lettuce leaf around barbecued meat, is said to cleanse the blood and aid digestion. Chicken and pork are considered the first steps to obesity, so are largely avoided. Nuts are supposed to be good for pregnancy as well as the skin; dried red dates and bellflower root for coughs and colds and raw potato juice for an upset stomach, while dried pollack with bean sprouts and tofu is said to be good for hangovers.

Much of Korean history was characterized by the struggle between the supporters of Buddhism and Confucianism for control of the system of patronage; this consequently also greatly influenced the food. The Silla Kingdom, based on Kyongju, united the Korean nation for the first time in the 7th century, giving birth to a long period of Buddhist culture. This culture continued to flourish into the Koryo Dynasty (ad 935-1368). However, although Koryo patronized Buddhism and the monks played an important role in national affairs, the Koryo kings also adopted Confucian-style government bureaucracy and civil service examinations from China. By the time Genghis Khan's Mongol alliance invaded Korea in 1231, the Koryo court had become torn between Confucian reform and the age-old Buddhist cultural heritage. A treaty made with China in 1279 gave Koryo semi-autonomy but required Korean princes to reside in the new Mongol capital at Beijing; they also had to marry Mongol princesses.

When the Ming Dynasty was established in China in 1368, and the Mongols were driven out, Koryo looked like the next prize on the list. However, the invading armies of the Ming Chinese were driven back by Yi Sog-gye, a fiery Korean commander who deposed the king of Koryo and invoked the Mandate of Heaven to establish his own Yi Dynasty.

The Yi Dynasty lasted over 500 years and ended only with the annexation of Korea by Japan in 1910. Yi's first king was wily enough to reestablish tributary relations with China and to also adopt Confucianism as the state creed, renaming his kingdom Chosun, after China's ancient name for Korea. From then onwards, Confucianism steadily replaced Buddhism in national life; and in effect, Buddhism was banished to Korea's mountain temples. There, close to the forests and mountain streams, Buddhist monks continued to study the scriptures. They also developed a "mountain cuisine" that has become the foundation of Korean cooking today. For example, meat, which is forbidden to the Buddhist monk, and anything that is strong smelling, such as garlic and spring onion, did not feature in temple cuisine. While modern Korean Buddhism is not so rigid about garlic, this cuisine has retained its traditional dependence on roots, grasses and herbs. Today, the visitor to any temples from Seoraksan in the northeast to Chirisan in the south is greeted by piles of mushrooms, roots and medicinal herbs on sale at the entrance. A typical temple meal consists of soup, rice and namul, vegetable dishes, in which the vegetables are gathered from the woods and the hills.

The collected roots and grasses are then prepared simply with soy sauce, crushed garlic, sesame seeds, sesame oil and seasonings. The preparation of namul varies from region to region, but the dishes are exactly the same as the side dishes of namul that accompany family and restaurant meals in Korean cities and towns, consisting of appetizers of shepherd's purse, mugwort, parsley and sow thistle; namul of wild aster, bracken, royal fern, marsh plant, day lily, aralia roots and bellflower, to name just a few.

Other stalwarts of the Korean table originate from the mountains, too, such as vegetable pancakes or jeon, which are usually filled with lentils or leeks and are sometimes fashioned in the shape of a flower.

The Culinary Tour of the Peninsula

Kyonggido Province surrounding Seoul offers rice and grain farmlands, vegetables from the eastern mountains and seafood from the Yellow Sea. Simple fare, served in generous, rather unspicy portions, include beef rib soup (galbitang), made of well-marbled short ribs boiled for as long as it takes to draw out the marrow; beef stock soup (gomtang), boiled with beef entrails and radishes; and the springtime shepherd's purse soup