Food has always been a big part of my life. Being born into a rather food-obsessed family, with a mother who took the time to cook everything from scratch, I was constantly surrounded by authentic home-cooked Korean food as a child.

Our back porch showcased half a dozen clay pots (onggi) with fermenting delights inside, everything from kimchi to gochujang to doenjang. The laundry room teemed with jars and containers stacked precariously, filled with fermenting drinks, bowls full of soaking tripe, mung beans, beansprouts or rice. The adjoining garage had rows of drying seaweed on hangers, chillies and a foil-wrapped charcoal grill for barbecues perched in the corner. Even family hiking trips often turned into impromptu foraging ventures, with my mum always on the look out for wild garlic, bracken root and chives.

My sister and I were often enlisted to help in this effort to get a taste of home so far from home. Mountains of beansprouts had to be picked, hundreds of dumplings stuffed, perilla leaves (ggaennip) gathered from our garden and towers of seaweed brushed with oil and toasted. It was all part of my daily life, and my memories surrounding food run deep.

I was born in Summit, New Jersey, and grew up in the modest suburb of Berkeley Heights. My father, a North Korean war refugee, immigrated to the United States in 1967, along with most of his graduating class from Seoul National University College of Medicine. My mum, from Icheon, a city just outside of Seoul, immigrated to the United States on her own in 1968 after being awarded a scholarship to obtain a masters degree in chemistry from Ohio State University. My parents met and married in the States and eventually moved to the East Coast where I was born. I had a typical tiger mother upbringing, with all the torturous piano lessons that came with it. I was on a typical Asian fast track to achieve and eventually found my way to Columbia University and then to Wall Street, where I sold fixed income derivatives for a number of years. I must admit, it was a fun time in my life. My friends and I ripped round New York City, with a bit of cash in hand, single, working hard and playing even harder. But something was missing I realized I didnt love my job. It was merely a means to an end. And so the soul-searching began.

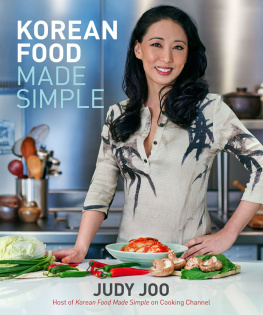

I always felt the lure of cooking, but didnt necessarily think that I could become a chef, per se. Nonetheless, after having an epiphany, I took the plunge and quit my fancy Wall Street job to embark on a culinary journey. I duly enrolled in cooking school at the French Culinary Institute (now the International Culinary Center) in New York and then went on to work in the industry in various capacities. Fast-forward a bit, and I became an Iron Chef for the U.K. I host my own cooking show, Korean Food Made Simple, and I have become a regular face on Food Network. More recently, Ive opened my own restaurant in London and Hong Kong, Jinjuu, where Im the Chef Patron.

I never really thought any of the prior was possible. Certainly not when you start late in the industry. But it just goes to show that a bit of hard work and dedication can take you anywhere.

In this book, youll find many modern Korean-influenced recipes. I am a French-trained Korean American Londoner, and the different influences in my life show up in my cooking. I grew to love Mexican food while living in California, and the flavours blend well with those found in Korean cuisine. Using matzo meal in my fried chicken seems very natural to me, being a New Yorker. Plus, dishes such as disco fries are a nod to my time growing up in Jersey and eating in the diners off the motorway. I also was specifically trained in pastry arts, so youll see a lot of my classic French training reflected in the sweets chapter. Although I do like traditional Korean desserts, I find that they do not translate well to the Western palate. Traditional Korean ingredients, however, do prove to meld beautifully in classic Western desserts.

Some recipes harbour a bit of a cheffy element and others are quite simple, rustic and easy for anyone to do. Regardless, I hope you try and learn to love the flavours of Korea, and incorporate a few Korean ingredients into your everyday cooking.

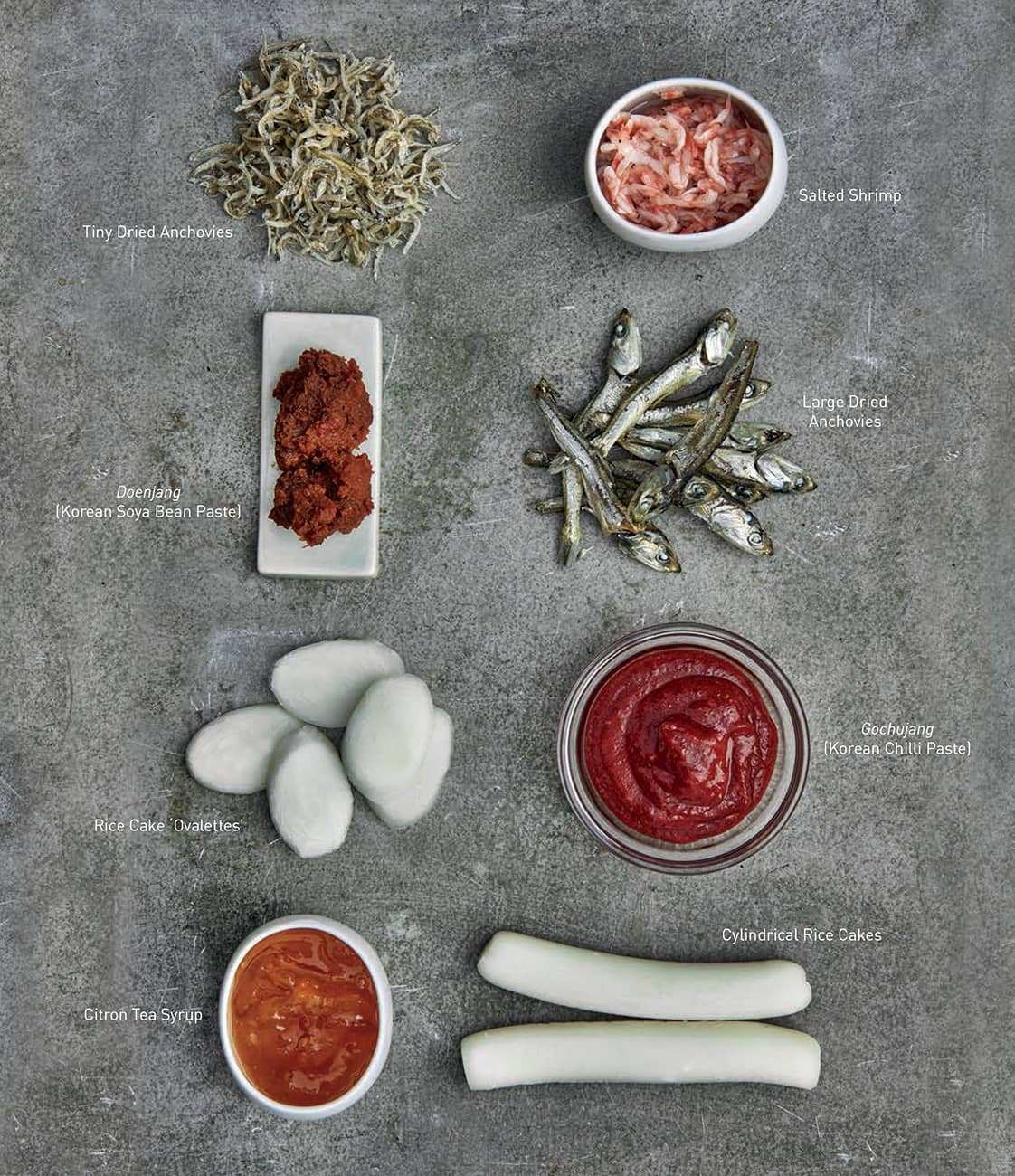

THE KOREAN STORECUPBOARD

There are a number of staple items necessary to successfully embark on a journey of Korean cooking.

Asian Pears (Bae)

Asian pears, also called Nashi or apple pears, are one of the sweetest and most popular fruits in Korea. Round like an apple, but texturally like a crisp pear, these large fruits are ambrosial and delectably juicy. The most famous ones are from the southern town of Naju, and these varieties can grow as big as melons. Eaten fresh or used to marinate meats, or even in kimchi, these pears are wonderfully versatile.

Brown Seaweed (Miyuk)

Miyuk is a dried seaweed that is considerably thicker than .

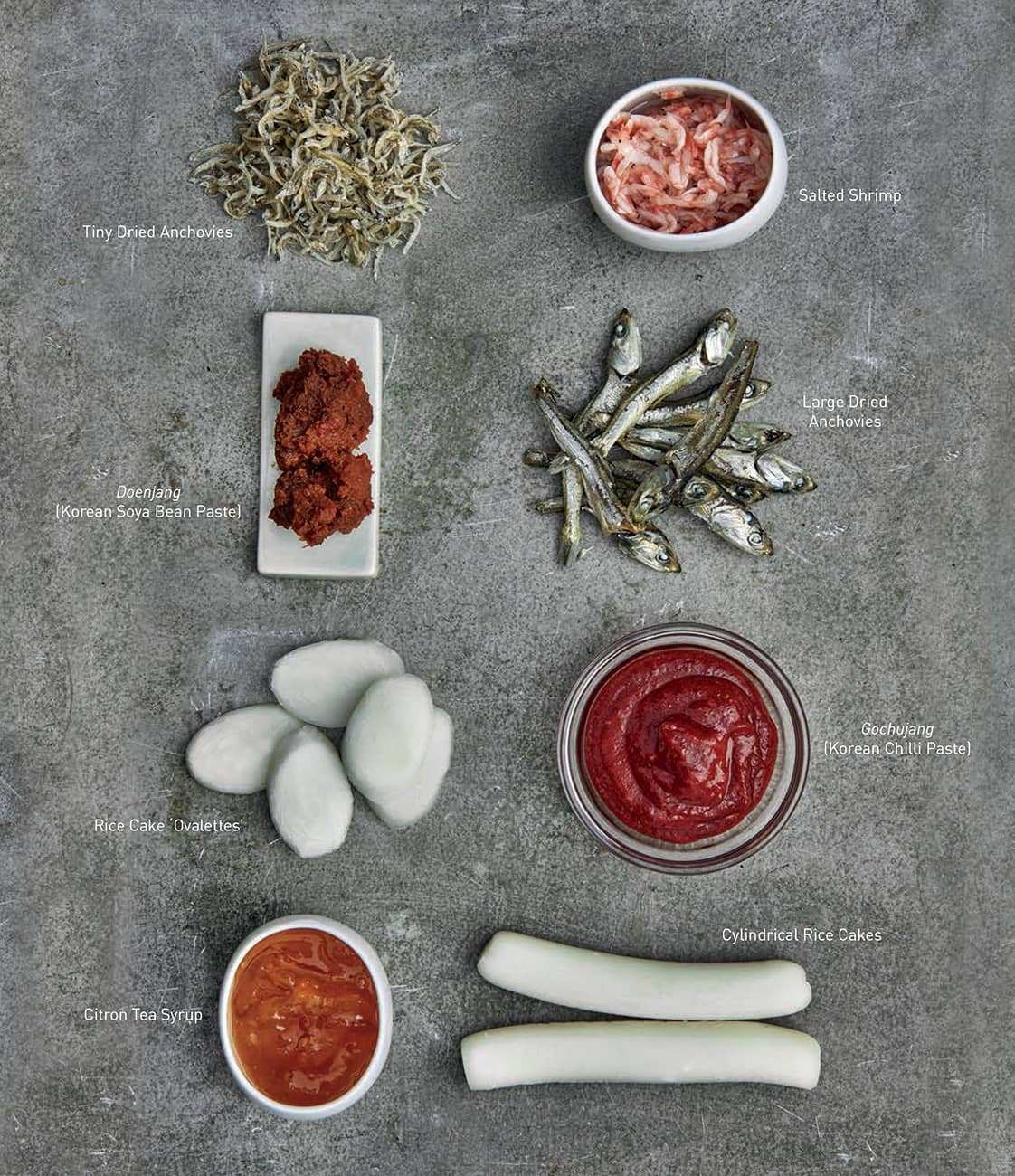

Citron Tea Syrup (Yujacha)

This marmalade-like citron syrup or honey is often used for making tea. Technically, it is not citron but yuja, known as yuzu in Japan, a fragrant and floral citrus fruit that tastes something like a lemon crossed with a tangerine. I use this for tea as well as in desserts and savoury dishes.

Doenjang (Korean Soya Bean Paste)

This dark brown and richly flavoured paste is made from fermented soya beans, and has a 2,000 year history. It is coarser (often contains whole beans) and stronger in flavour than its Japanese counterpart, miso. The soya beans are boiled, pressed into blocks called meju, and then hung to dry using dried rice stalks, which are rich in bacteria (bacillus subtilis) that starts the fermentation process. Once the meju is fermented and dried enough (depending on the size, up to 50 days), the blocks are placed in salted water and allowed to ferment further, for up to 6 months. Once the process is complete, the liquid is drained off this is used to make soy sauce. The remaining bean pulp is then made into