CONTENTS

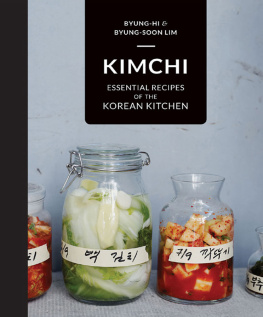

THE LIM FAMILY AND ARIRANG

KOREAN KIMCHI IS neither a dish, nor a meal, nor a recipe it is a task to be done over time. Neither is kimchi just one flavour it is layer upon layer of flavours: hot and acidic, salty and pungent. These flavours also change, not just by virtue of the produce that was used for the particular batch, but also every time you open the lid of the kimchi jar.

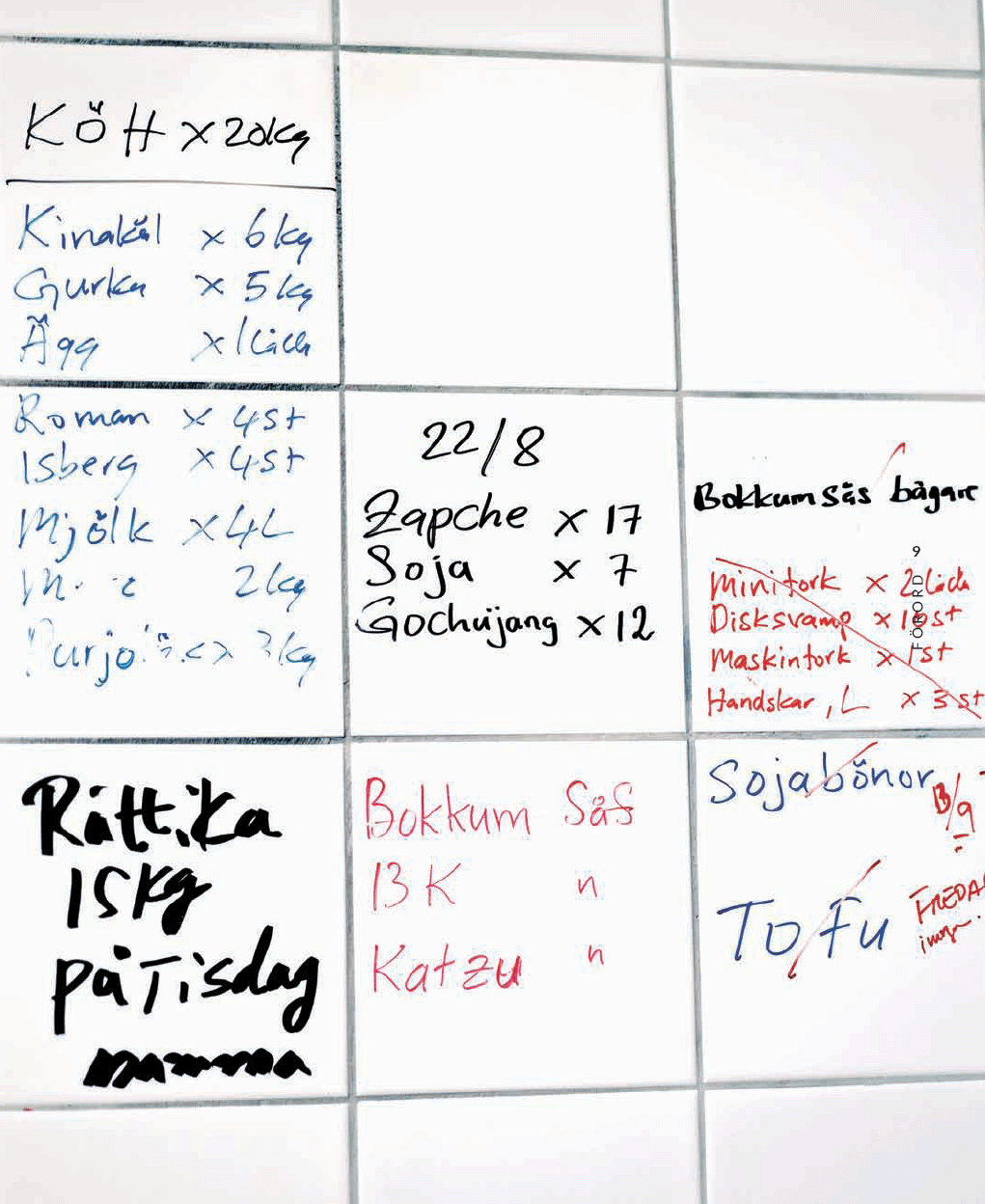

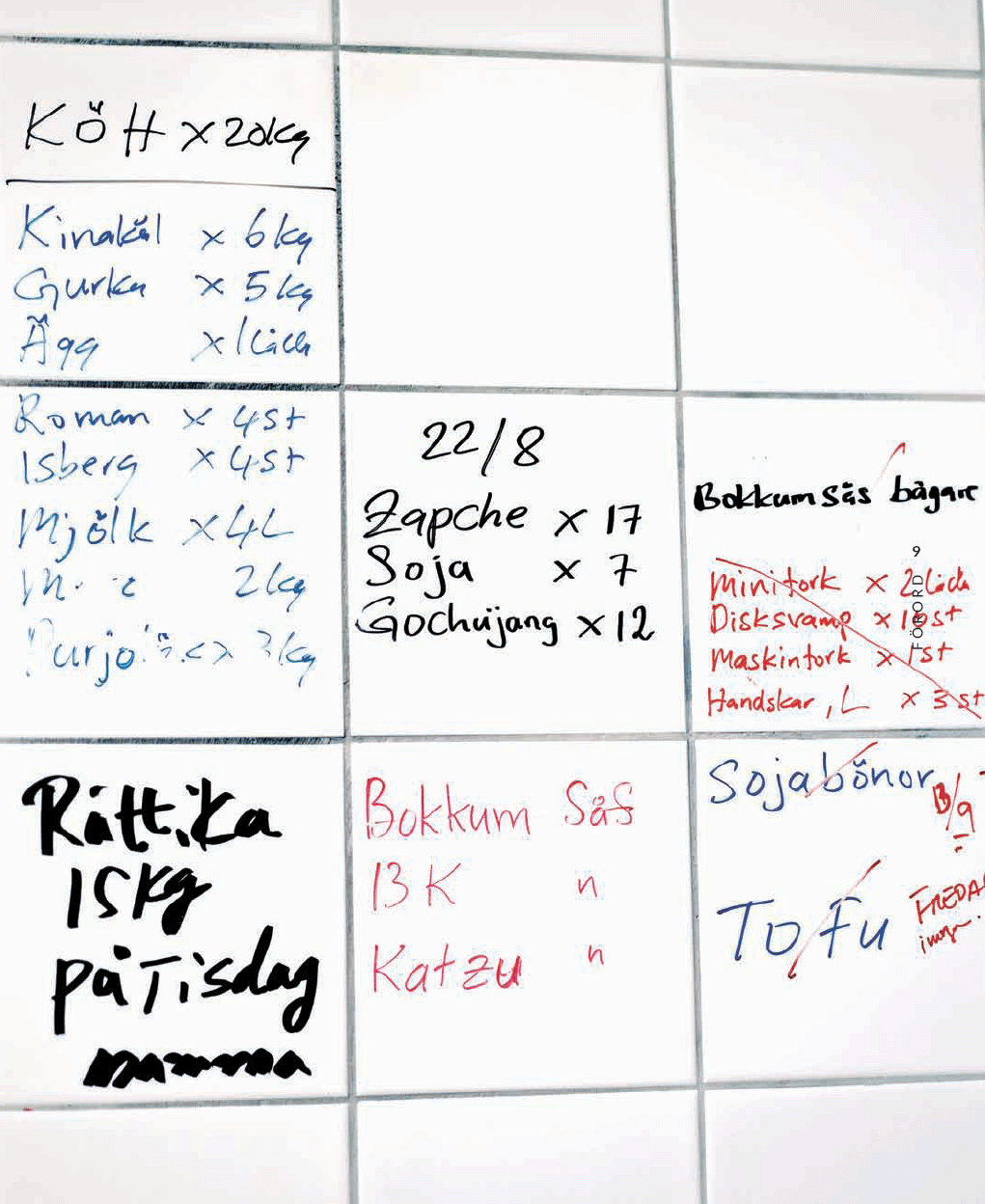

The kitchen at Arirang restaurant is quiet. No hustle, no bustle, despite the crowded dining room outside. Thats how the four women behind Arirang want it. Instead of the noise, its the smells that get the attention: the simmering oxtail stock, the grated ginger, the hot steam from the rice, the pork belly being grilled.

The four family members two sisters, one mother and an auntie make up the heart of Arirang. The Korean restaurant on Luntmakargatan in Stockholm has been a hub for Korean food culture in Sweden for nearly 40 years. The history of Arirang began when the violin player Yoo-Jik Lim moved to Sweden from Korea in 1960 to work as a musician. At a party in Stockholm he met Im Boo Mee Ja, a Korean nurse who had just travelled to Sweden on an exchange programme. They married and had two daughters, Byung-Hi and Byung-Soon. Later their auntie Im Kee Sun came over from Korea to help look after the girls.

Its always mum who tastes the kimchi when its ready, Byung-Soon says. The whole kitchen stops for a second and everyone stands up straight and looks at mum in great anticipation. Hopefully shell say it tastes good. Then we breathe out and get back to our work.

Byung-Soon is stuffing halved Chinese leaf into a large plastic container in preparation for the fermentation. Not too tight but not too loose either. The more times you make kimchi, the better feel youll get for the craft. All the steps are important, but its not especially difficult. The challenge is to have patience because the reward is still a couple of weeks away.

KOREA AND KIMCHI

THERE IS A Korean proverb that goes: If you have kimchi and rice you have a meal.

The Korean table offers a lot more than just rice and kimchi, but a Korea without kimchi is simply unimaginable. Korean cuisine is a grandiose firework display for all the senses, with kimchi as the common denominator.

The secret behind Korean food lies in the contrasts of flavour and colour, of texture and temperature. From the toasted aromas of sesame oil to the sting of the chilli paste. From the freshness of the ginger to the basic notes of the garlic. The warmth from the dolsot, the traditional hot stone bowl, stands in even greater contrast to the Water Kimchis cool brine. Kimchi becomes the thread that weaves all the small parts of Korean cooking together, spun from the fermented vegetables.

Many Koreans seem obsessed with kimchi; on average they eat approximately 100g of kimchi per person every day. That adds up to a lot of lacto-fermented vegetables a year, Ideally, these should be stored (free from smell) in a special kimchi fridge adapted for the home. The fact that in Korea there is a public institute set up to spread the gospel of kimchi around the world (it has even been commissioned to develop a special space kimchi for astronauts) seems to confirm this obsession. So, where does it come from?

Korea has four seasons, with a long, cold and stubborn winter. In the past, people had to stock up on large quantities of food in the autumn to see them through to springtime. Unlike most western cultures, despite the modernisation of homes with refrigerators, freezers and the development of chemical preservatives, Koreans have stuck with their traditional preserving methods. Still today lacto-fermentation is celebrated as the backbone of the household even though far from everyone in Korea still does their own fermenting.

Another explanation to the obsession with kimchi is of course its flavour. For the western palate a certain acquirement might be necessary, because the flavours of fermentation are rarely subtle. Kimchi has a bold flavour chilli-hot with plenty of saltiness and a distinct acidity, a thoroughly umami flavour from the fish sauce and that special somewhat bittersweet experience of fermentation. Just as with truffles, kimchi is divisive, youre either not that keen or you simply cant stop eating it.

To ferment, to let bacteria work on food, can seem a little trivial in the great world of cooking. But fermentation is actually so common that we almost stop thinking about it: bread, wine, yoghurt, chocolate, cheese, tea in all of these very ordinary products a bacterial process is often a pre-requisite. Fermentation is nothing strange, and the result does not have to taste like the notoriously pungent fermented herring. Kimchi is unique to Korea, but the process of lacto-fermenting vegetables pops up in many cultures around the world.

The preservation of food has historically been the crucial factor of mans survival. Fermentation is about catching the vegetable at its best and making the degradation process that follows controlled and slow, in order to create a prolonged period of use and enjoyment for us humans.

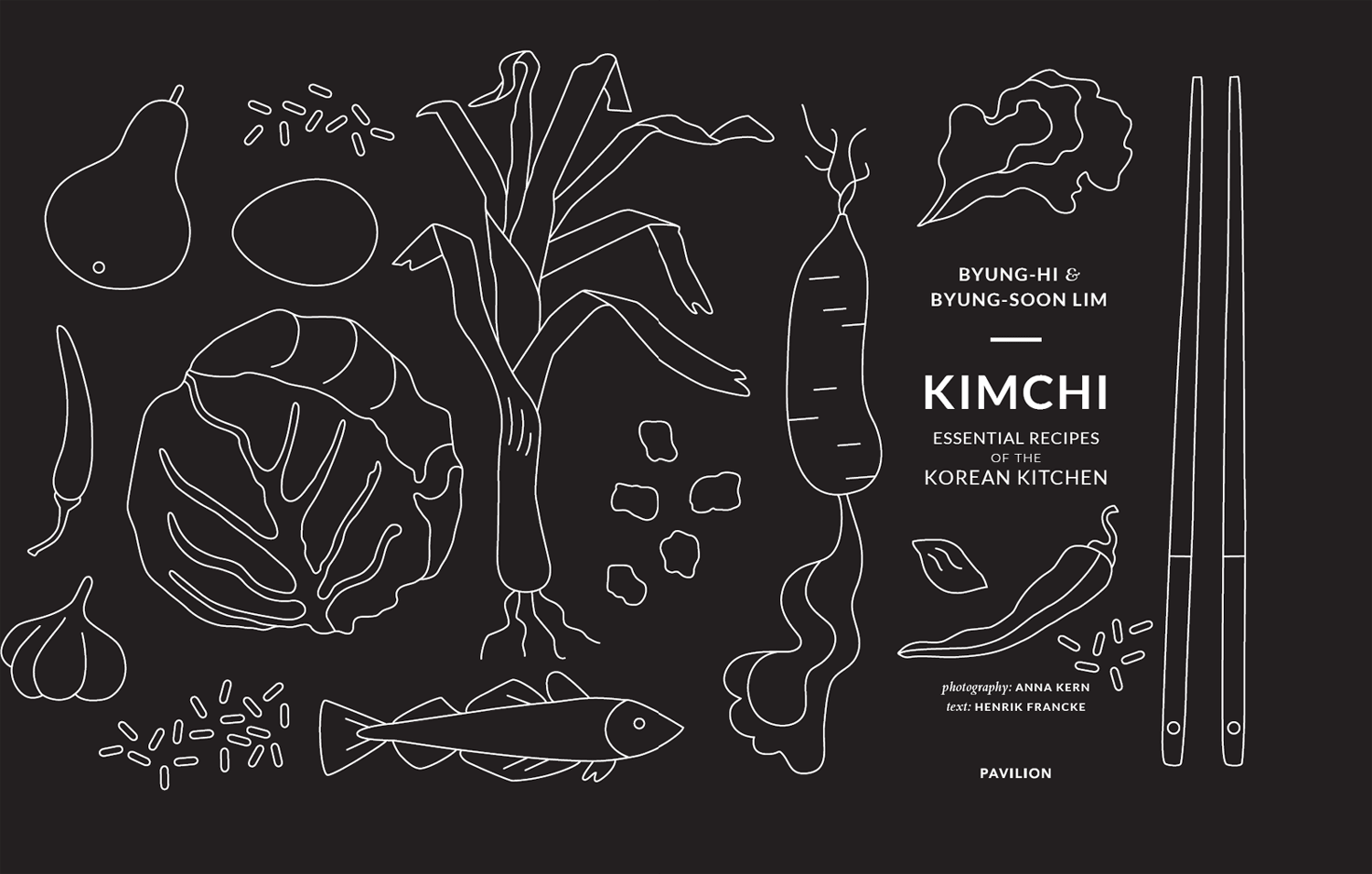

Are you ready to throw yourself into the wonderful world of fermentation? In this book youll learn the techniques and methods to make you own kimchi, using Chinese leaf, daikon, cucumber, squash, white cabbage, carrot, oysters and ginseng, to name but a few. To embrace Korean fermentation is like opening the door to a new, healthy world full of flavour.

WHAT IS KIMCHI?

THE MOST COMMON kimchi recipe, paechu, is made using Chinese leaf, but a similar method is used for a lot of different vegetables: daikon, squash, cucumber, to name a few. Its said that there are over 200 different variations. The craft of kimchi-making in Korea is many thousand years old, but the kimchi then looked different and didnt taste the same as today chillies, for example, werent introduced in Korea until the 17th century. In the same time-period, kimchi also developed to contain shellfish and fish. Traditionally, kimchi was made in late autumn, but today there are lots of varieties to eat all year round; you just use whatever produce the season offers.

Kimchi is sometimes called Asian sauerkraut, and on a bacterial level the comparison isnt completely wrong. Both kimchi and sauerkraut are fermented with help from lacto-bacteria. Unlike sauerkraut, however, the kimchi cabbage is left in a salt brine for a day before the fermentation starts. In terms of flavour, the similarities are few and far between, as the kimchi loads up on ginger, garlic, leek and Korean chilli powder. Furthermore, for the kimchi you dont only add salt, but also sugar as extra nutrition for the bacteria.

MORE THAN JUST TASTY

In Korea people pay close attention to the health benefits of food, and you often medicate with help from various foods and dishes. Ginseng, algae, soya beans everything has its own particular use. Fermented foods especially have an extra-healthy reputation due to the living bacteria culture.

Next page