A Country Year

Living the Questions

Sue Hubbell

Illustrations by Liddy Hubbell

The Wild Things helped

Contents

Foreword

There are three big windows that go from floor to ceiling on the south side of my cabin. I like to sit in the brown leather chair in the twilight of winter evenings and watch birds at the feeder that stretches across them. The windows were a gift from my husband before he left the last time. He had come and gone before, and we were not sure that this would be the last time, although I suspected that it was.

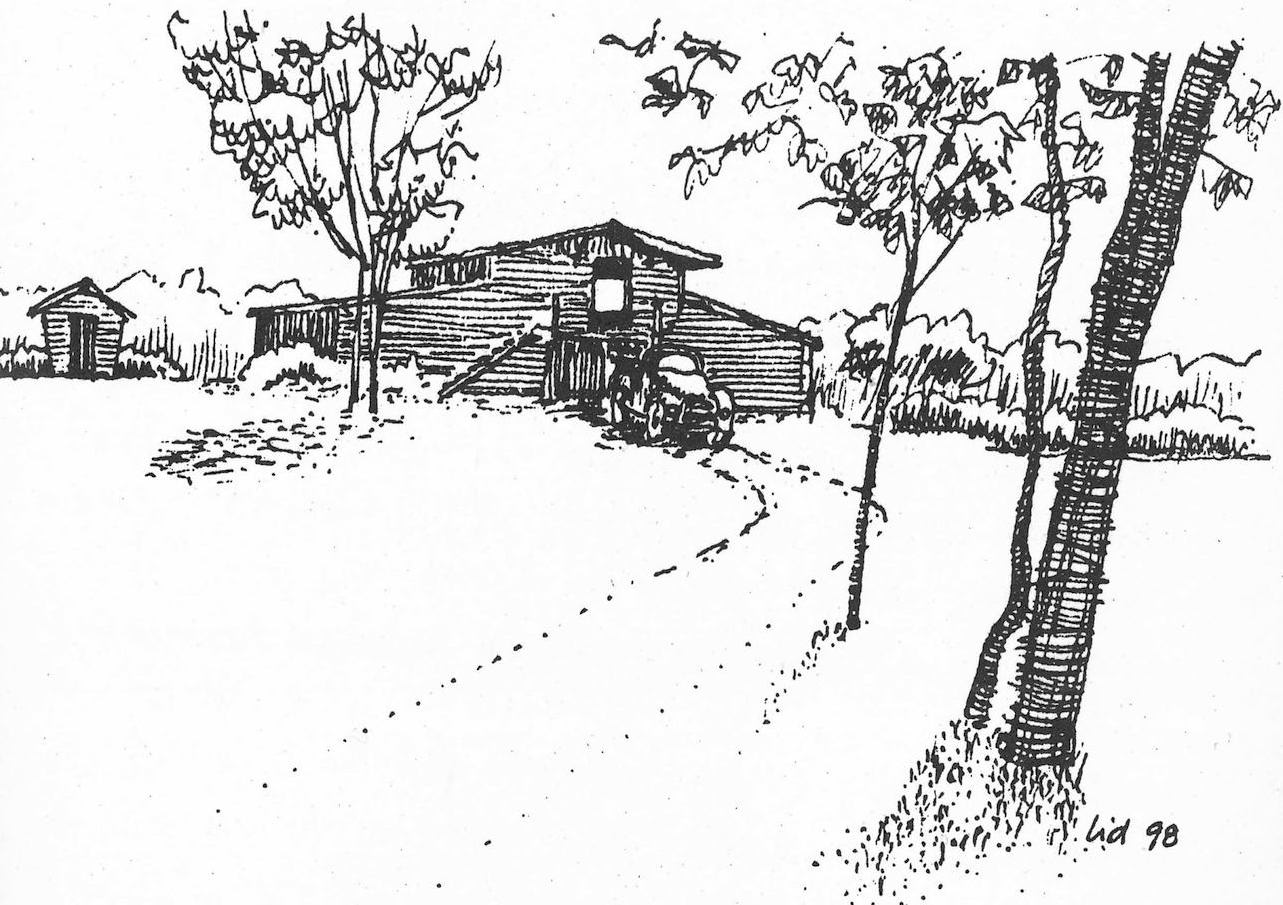

I have lived here in the Ozark Mountains of southern Missouri for twelve years now, and for most of that time I have been alone. I have learned to run a business that we started together, a commercial beekeeping and honey-producing operation, a shaky, marginal sort of affair that never quite leaves me free of money worries but which allows me to live in these hills that I love.

My share of the Ozarks is unusual and striking. My farm lies two hundred and fifty feet above a swift, showy river to the north and a small creek to the south, its run broken by waterfalls. Creek and river join just to the east, so I live on a peninsula of land. The back fifty acres are covered with second-growth timber, and I take my firewood there. Last summer when I was cutting firewood, I came across a magnificent black walnut, tall and straight, with no jutting branches to mar its value as a timber tree. I dont expect to sell it, although even a single walnut so straight and unblemished would fetch a good price, but I cut some trees near it to give it room. The botanic name for black walnut is Juglans nigraBlack Nut Tree of God, a suitable name for a tree of such dignity, and I wanted to give it space.

Over the past twelve years I have learned that a tree needs space to grow, that coyotes sing down by the creek in January, that I can drive a nail into oak only when it is green, that bees know more about making honey than I do, that love can become sadness, and that there are more questions than answers.

SPRING

SUMMER

AUTUMN

WINTER

SPRING

The river to the north of my place is claimed by the U.S. Park Service, and the creek to the south is under the protection of the Missouri State Conservation Department, so I am surrounded by government land. The deed to the property says my farm is a hundred and five acres, but it is probably something more like ninety. The land hasnt been surveyed since the mid-1800s and it is hard to know where the boundaries are; a park ranger told me he suspected that the nineteenth-century surveyor had run his lines from a tavern, because the corners seem to have been established by someone in his cups.

The place is so beautiful that it nearly brought tears to my eyes the first time I saw it twelve years ago; I feel the same way today, so I have never much cared about the number of acres, or where the boundary lines run or who, exactly, owns what. But the things that make it so beautiful and desirable to me have also convinced others that this is prime land, too, and belongs to them as well. At the moment, for instance, I am feeling a bit of an outsider, having discovered that I live in the middle of an indigo bunting ghetto. As ghettos go, it is a cheerful one in which to live, but it has forced me to think about property rights.

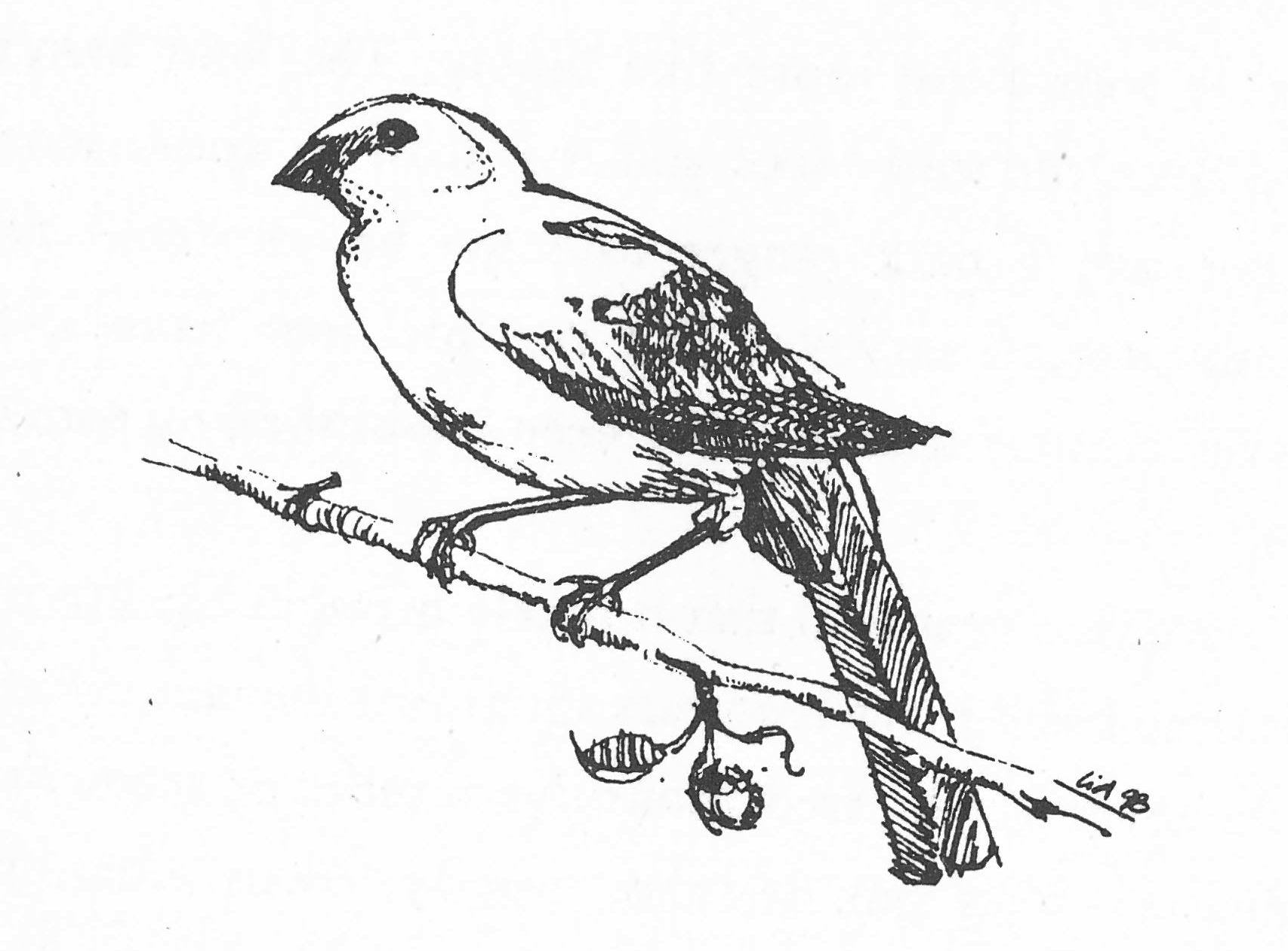

Indigo buntings are small but emphatic birds. They believe that they own the place, and it is hard to ignore their claim. The male birdsbrilliant, shimmering blueperch on the garden posts or on top of the cedar trees that have taken over the pasture. From there they survey their holdings and belt out their songs, complicated tangles of couplets that waken me first thing in the morning; they keep it up all day, even at noon, after the other birds have quieted. The indigo buntings have several important facts to tell us, especially about whos in charge around here. The dull brown, sparrowlike females and juveniles are more interested in eating; they stay nearer the ground and search the low-growing shrubs and grasses for seeds and an occasional caterpillar, but even they know whats what. One day, walking back along the edge of the field, I came upon a young indigo bunting preoccupied with song practice. He had not yet dared take as visible a perch as his father would have chosen, but there he was, clinging to a bare twig and softly running through his couplets, getting them all wrong and then going back over them so quietly that had I not been within a few feet of him I would not have heard.

Another time I discovered that the back door of the honey house had blown open and the room was filled with a variety of winged creatures. Most were insects, but among them I found a half-grown indigo bunting who had blundered in and was trying to find his way out, beating his small wings against the screened window. Holding him carefully, I stroked the back of his neck to try to soothe him, but discovered that his heart was not beating in terror. Perhaps he was so young that he had not learned fear, but I prefer to think that like the rest of his breed he was simply too pert and too sure of his rights to be afraid. He eyed me crossly and tweaked my giant thumb with his beak to tell me that I was to let him go right this minute. I did so, of course, and watched him fly off to the tall grasses behind the honey house, where I knew that one family of indigo buntings had been nesting.

Well, they think they own the place, and their assurance is only countered by a scrap of paper in my files. But there are other contenders, and perhaps I ought to try to take a census and judge claims before I grant them title. There are other birds who call this place theirsbuzzards, who work the updrafts over the river and creek, goldfinches, wild turkey, phoebes and whippoorwills. But it is a pair of cardinals who have ended up with the prize piece of real estatethe spot with the bird feeder. I have tapes of birdsongs, and when I play them I try to skip the one of the cardinal, because the current resident goes into a frenzy of territorial song when he hears his rival. His otherwise lovely day is ruined.

And what about the coyote? For a while she was confident that this was her farm, especially the chicken part of it. She was so sure of herself that once she sauntered by in daylight and picked up the tough old rooster to take back to her pups. However, the dogs grew wise to her, and the next few times she returned to exercise her rights they chased her off, explaining that this farm belonged to them and that the chicken flock was their responsibility.