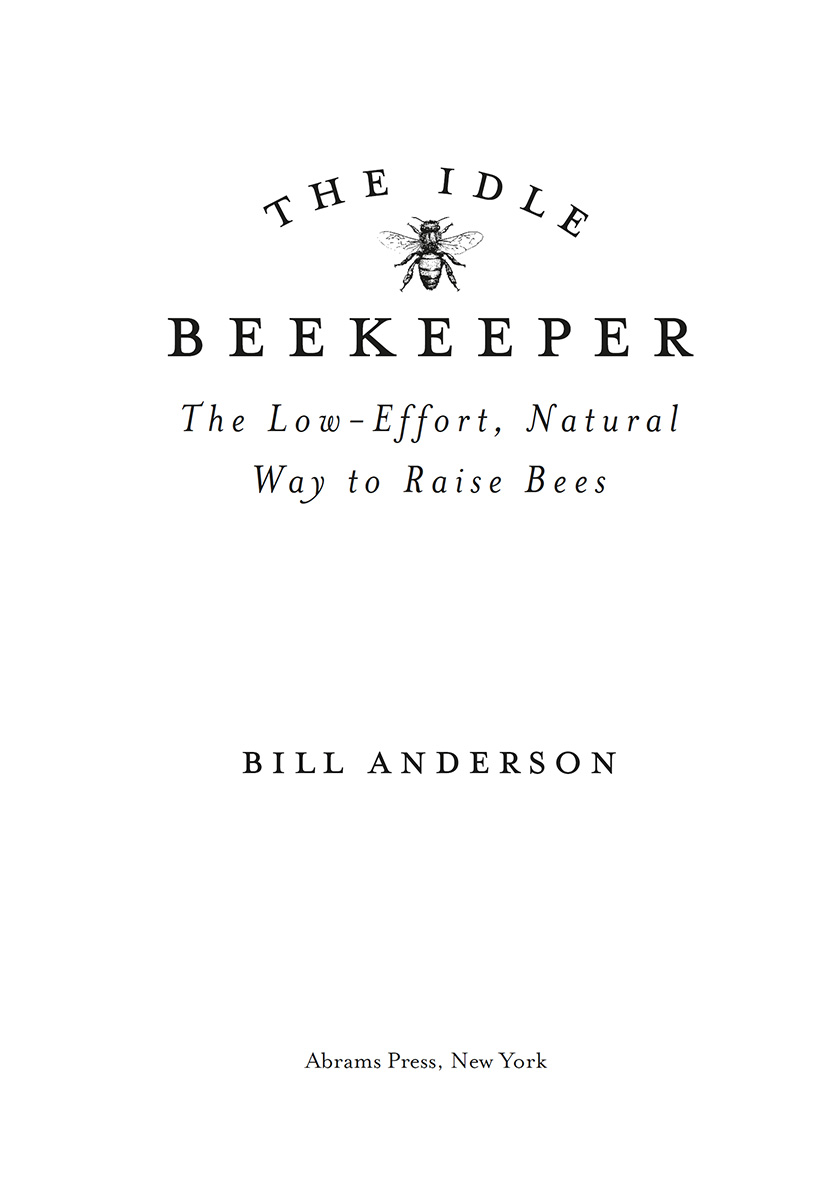

Copyright 2019 Bill Anderson

Cover 2019 Abrams

Published in 2019 by Abrams Press, an imprint of ABRAMS. All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

PHOTO CREDITS: from The Animals and Man; An Elementary Textbook of Zoology and Human Physiology (Henry Holt and Company: New York, NY: 1911), courtesy of Internet Book Archive.

All other images courtesy of Bill Anderson.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019932568

ISBN: 978-1-4683-1706-0

eISBN: 978-1-4683-1707-7

Abrams books are available at special discounts when purchased in quantity for premiums and promotions as well as fundraising or educational use. Special editions can also be created to specification. For details, contact specialsales@abramsbooks.com or the address below.

Abrams Press is a registered trademark of Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

ABRAMS The Art of Books

195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007

abramsbooks.com

To Lesley, queen to my drone and our brood

The keeping of bees is like the direction of sunbeams.

HENRY DAVID THOREAU

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Why Now?

Almost everyone now knows how much we all depend on bees. In 1958 the Chinese found out the hard way in a cautionary tale of biblical proportions. Agricultural targets were not being met, and Chairman Mao decided that sparrows were responsible for eating intolerable amounts of the peoples rice crops. He orchestrated a hugely successful campaign to eradicate them. The sparrows. The whole population was encouraged to get involved. Good citizens used guns and catapults to shoot the birds. They banged pots and pans, beat drums: anything to scare the sparrows from landing, forcing them to keep flying until they fell from the sky, dead from exhaustion. Nests were destroyed, eggs smashed, nestlings killed, and the sparrows were driven to near-extinction.

But with the sparrows gone, the insects they ate flourished. Plagues of locusts wreaked even greater devastation on the crops. Chinese scientists then actually looked inside dead sparrows stomachs and discovered 25 percent human crops and 75 percent insects. Oops. So now the insects got it. Patchy and panicky misuse of pesticides like DDT not only wiped out the locusts, it killed all the pollinators as well. The bees werent the only innocent victims of these acts of devastating human ignorance: the ensuing ecological disaster exacerbated the Great Chinese Famine in which at least twenty million people died of starvation.

In 2012 a study commissioned by Friends of the Earth estimated that if the United Kingdom couldnt rely on insect pollinators and had to do the job ourselves by hand, it would cost the economy $2.3 billion a yearfor a green and pleasant land of sixty million people that doesnt grow enough food to feed itself.

That same year I got my first bees. But it wasnt as a result of terrifying, apocalyptic statistics. Id been in a beautiful English garden directing Lewis, a television drama whose pilot Id helmed, in the oddly nautical language of our industry. We were filming a scene that involved a fictional family enjoying a relaxing lunch alfresco. The laws of filmmaking usually insist upon hurricanes or snow on these occasions, but it appeared we had been given special dispensation: it was merely unseasonably cold. Actors were huddled like convicts in huge quilted thermal coats sprayed with stenciled coat hanger symbolswardrobe department graffiti to discourage any thoughts of theft or style. Inelegant feather puffas were abruptly plucked away at the last moment before shooting the illusion of a midsummer, hypothermia-free take.

I was talking to the cameraman about how we might make the next freezing shot look warm and golden, and though he seemed to be listening intently, he began to slowly lower himself down to the lawn where we were standing and surreptitiously picked something up off the ground. Dropped litter I assumed, and carried on. But then, without taking his eyes off me, he tried to pretend that he wasnt gently blowing into the fist hed made around the litter. Mysterious. He appeared to be still diligently listening to what I was saying, but I wasnt: I noticed hed put his other hand into the pocket of his down jacket, a much more efficient way to keep it warm, so what was with the blowing?

Like a schoolboy caught stealing in a sweet shop, Paul slowly unfurled his fingers to reveal an insect lying on its back in the palm of his hand. Six legs skywards.

Looks like a dead bee, I offered, none the wiser.

Well, it might be... Paul looked intently at the bee.

I didnt have to: Its definitely a bee.

Yes. But it might not be dead. If they stop moving for too long on a cold day, they can cool down so much their flight muscles stop working. Then theyre stuck outside and theyll cool down even more and die. But sometimes, if you warm them up a little...

... Two of the six legs twitched...

... just get them going again...

... The dead bee flipped over off its back and started crawling on Pauls warming palm...

... they can fly back to the hive where theres warmth and food...

... Lift off! I watched Pauls gaze following the bee as it flew off purposefully into the heavens. Id just witnessed a resurrection.

Not at all! I just gave her a helping hand, he said, but his eyes were twinkling with joy.

French philosopher Albert Camus said, Life is a sum of all your choices. As a storyteller I spend most of my time interrogating characters choices with the question Why now? Its the crux of dramatic narrative. All of us are all too aware that we often avoid making those significant life choices that will change everything: we know they will define us, determine our future, but how to get them right? The circumstances that demand such a choice may have been pressing for years, so when we finally commit and decide to act, what happened? What was the trigger? Why now?

I later found out that Paul, the cameraman shooting my drama, had another life: as Bond... Paul Bond, he was secretly a World Champion beekeeper. Even later I realized my choice to keep bees had secretly been made the moment that bee flew from his hand.

Right now you might like to consider why youve chosen to be reading this book at this particular moment.

The writing of it goes back to another, altogether grander English garden where the annual Port Eliot Festival beautifully meanders by a tidal estuary on the south coast. In the summer sunshine on the riverbank lawn I came across not a catatonic bee but a large tent: The Idler Academy of Philosophy, Husbandry, and Merriment. The use of that last word outside the context of Christmas or alcohol brought a smile to my face and drew me inside. It was love at first sight. The Idlers motto is Libertas per cultum and as well as teaching you Latin so you can knowingly pursue freedom through culture, philosophy, astronomy, calligraphy, music, business skills, English grammar, ukulele, public speaking, singing, drawing, self-defense, taxidermy, harmonica, and many other subjects were also on the Idle menu along with much hilarity and merriment. But not Idle beekeeping.

Next page