The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

I have come for my courage, announced the Lion, entering the room.

Very well, answered the little man; I will get it for you.

He went to a cupboard and reaching up to a high shelf took down a square green bottle, the contents of which he poured into a green-gold dish, beautifully carved. Placing this before the Cowardly Lion, who sniffed at it as if he did not like it, the Wizard said:

Drink.

What is it? asked the Lion.

Well, answered Oz, if it were inside of you, it would be courage. You know, of course, that courage is always inside one; so that this really cannot be called courage until you have swallowed it. Therefore I advise you to drink it as soon as possible.

The Lion hesitated no longer, but drank till the dish was empty.

How do you feel now? asked Oz.

Full of courage, replied the Lion, who went joyfully back to his friends to tell them of his good fortune.

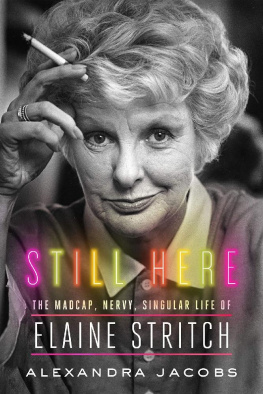

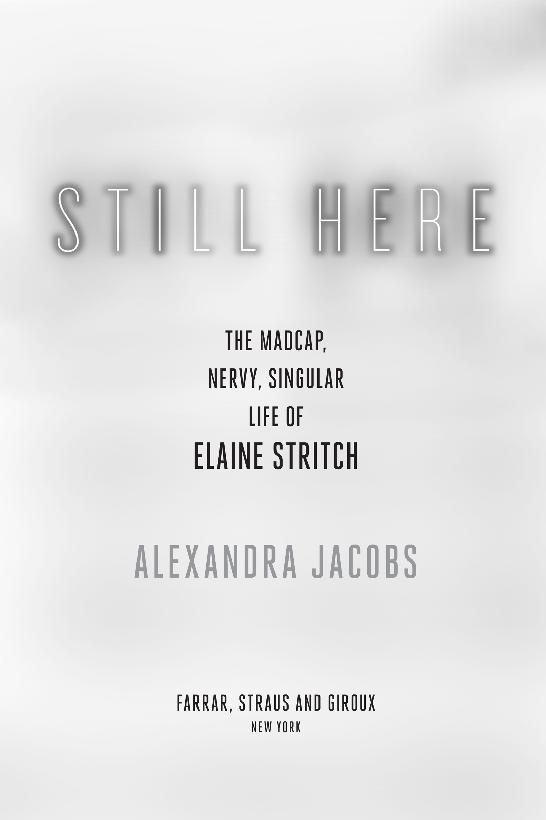

O n the afternoon of November 17, 2014, hundreds of people made their way through a dark rain toward the Al Hirschfeld Theater on West Forty-Fifth Street in New York City. Settling with a certain expectant jollity into its plush red seats were actors famous and obscure, executives, playwrights, press agents, journalists, out-of-towners, a bronzed billionaire fashion designer whod pulled up in a limousine, and ordinary civilians arriving on foot with their busted umbrellas.

They had arrived not for a matineefor this was a Monday, when Broadway stages are by long custom darkbut to pay homage to Elaine Stritch, the indefatigable-seeming entertainer who at eighty-nine had died of stomach cancer four months earlier in Birmingham, Michigan, a leafy suburb northwest of Detroit. Not for Stritch the mealymouthed passed away; her preferred euphemism was left the building. It indicated her fundamentally citified view of life.

Plenty of her contemporaries were present, including Hal Prince, the director and producer whose compactly commanding stance and twenty-one Tonys gave him a Napoleonic air, and Liz Smith, the platinum-haired gossip columnist known as the grande dame of dish. Some in the audience were puzzled, though, by the absence of Stephen Sondheim, the composer and lyricist whose virtuosic work Stritch was devoted to above all others, whose approval she craved more than anyone elses. (He had a respiratory infection that day, he said later. But he had also refused an earlier invitation to speak, writing simply that he didnt know the honoree well enough, and sending organizers into frenzied analysis of what exactly that might mean.)

There were also others much younger, many of whom had discovered Stritch only after seeing her 2001 one-woman show At Liberty: the artful summation of her marathon career conducted with the sole prop of a barstool. Written with John Lahr, then The New Yorkers chief theater critic, its success had led to the recognition she had longed for since arriving in New York almost sixty years before. She was deemed a Living Landmark and joyously heralded by strangers in her regular and often untrousered patrols from the Carlyle on Madison Avenue, the last in a series of venerable hotels she had chosen to call home. So far as that went. I dont know if I really have any home, she said once. I dont know how I feel about home. I dont know where home is.

To the end she was both restless and routinized, selfish and generous, straightforward and elliptical. How do you solve a problem like Elaine Stritch? asked one of the many celebrities in attendance, the actor Nathan Lane. He was standing at a podium under a Hirschfeld line drawing of the honoree clutching, characteristically, a brandy snifter, made to publicize the 1996 revival of Edward Albees play A Delicate Balance. How do you hold a fucking moonbeam in your hand?

The crowd laughed knowingly at the profanity, which Stritch had deployed decades before it was common in polite society. This was one of several ways she had been ahead of her time or even somewhat out of time. She had chosen to live alone when the average woman of her Midwestern, Catholic, upper-middle-class background had become a Mrs. and a mother before age thirty. She had defied stereotypes of gender and age, projecting both feminine and masculine and refusing the slow fade accorded most in her profession (along with plastic surgery). She insisted on being seen and heard, felt and dealt with. She skirted high culture, low culture, and everything in between.

Though it was variously suggested Stritchs voice was infused with gravel, whiskey, or brassa writer for People magazine once compared it to a car shifting gears without the clutchher admirers from the music world had grown to include the longtime director of the Metropolitan Opera, James Levine; the indie rocker Morrissey; and the pop idol Elton John, who had sent half a dozen huge orchid plants to her small private funeral in Chicago with a card reading: You were a shining star.

Onstage at the Hirschfeld, Stritchs colleagues sang the numbers shed made her own. Bernadette Peters shrugged and mugged through the goofy and dated Civilization (Bongo, Bongo, Bongo), about a jungle native underwhelmed by Western society and its technological advancements. Laura Benanti and Michael Feinstein did the contrapuntal duet Youre Just in Love from Irving Berlins Call Me Madam, alternately plaintive and twinkling. Betty Buckley got the wistful ballad I Never Know When (to Say When), perhaps the sole keepsake from a largely forgotten 1958 musical called Goldilocks.

But by far the most affecting performance came toward the events end, when the lights dimmed and an image of Stritch herself materialized on a big screen, like a glamorous ghost, in what might have been called her prime had she not so forcefully redefined that term. Wearing an ensemble of white blouse and black tights cribbed from Judy Garlands famous Get Happy sequence but carried off even more effectively with her long, slim legs, she began the Sondheim song The Ladies Who Lunch, from the landmark 1970 musical Company, which was for so many years her signature anthem.

The Stritch-specter inhabited the dark world of the lyrics completely: cocking her silvery blonde head at the camera, enunciating, clasping her manicured hands as if in prayer, raising and furrowing professionally arched eyebrows, grinning, winking, nodding, jabbing, giving the okay sign, beckoning, pumping a fist, clawing, and throwing both hands up in a V shape that seemed to signify equally victory and defeat.

So heres to the girls on the go

Everybody tries

Look into their eyes,

And youll see what they know

Everybody dies.

Everybody dies, Prince had quoted at the podium, and paused. Im not so sure about Elaine.

Indeed, Stritch had been charged with such restless energy, one could be forgiven for believing she might yet emerge for one last encore from behind the Hirschfelds corrugated curtain. Zelig-like, she had witnessed the Ziegfeld Follies and MTV videos; known the era of blackface and performed for the countrys first African American president; and had her saucy one-liners (another brilliant zinger, per the Sondheim song) committed both to piles of yellowing telegrams and the online echo chamber of Twitter. For decades she had kicked up her heels; for decades more she had made a Sisyphean trudge through the twelve steps of recovery.