PROLOGUE

H E HAD BEEN VERY TALKATIVE UP TO THAT POINT, BUT WHEN WE got to the subject of the telegram, he went quiet for a moment. Then, snapping to attention, he began to intone in a voice so firm that it belied his eighty-five years: The battle is entering its final chapter. Since the enemys landing, the gallant fighting of the men under my command has been such that even the gods would weep.

The peaceful sun was pouring into the living room of the cramped house where the old couplehe was eighty-five, she seventy-five lived in Nangoku in Kchi Prefecture. On the comfortable, old-fashioned sofa sat an unopened box containing a robot dog that their grandchild had sent them from Tokyo as a substitute pet. How can I possibly be expected to make head or tail of the instruction manual at my age? the old man grumbled just a minute ago. Now, his voice quite transformed, he continued:

In particular, I humbly rejoice in the fact that they have continued to fight bravely though utterly empty-handed and ill-equipped against a land, sea, and air attack of a material superiority that surpasses the imagination.

One after another they are falling to the ceaseless and ferocious attacks of the enemy. For this reason, the situation has arisen whereby I must disappoint your expectations and yield this important place to the hands of the enemy. With humility and sincerity, I offer my repeated apologies.

Our ammunition is gone and our water dried up. Now is the time for us all to make the final counterattack and fight gallantly

His voice was growing a little hoarse, and the unexpected recitation came to an abrupt end.

The expression on his face now back to normal, he looked at me and smiled as if slightly embarrassed. Then, his expression serious once more, he said: For me that message is like a sutra. It was the last message his lordship left us. It still just comes out word perfect like that. I cant forget a single word of it.

The man Sadaoka Nobuyoshi was referring to as his lordship was none other than Lieutenant General Kuribayashi Tadamichi, commander in chief of Iwo Jima, the scene of some of the most savage fighting of the Pacific War. With a force of a little over twenty thousand men, Kuribayashi waged a campaign of unprecedented bloodshed and endurance.

Meticulous and rational in the way he fought, Kuribayashi inflicted enormous damage on the Americans after they landed before eventually switching to guerrilla tactics. Ultimately, Iwo Jima, which was thought likely to fall in five days, ended up holding out for thirty-six.

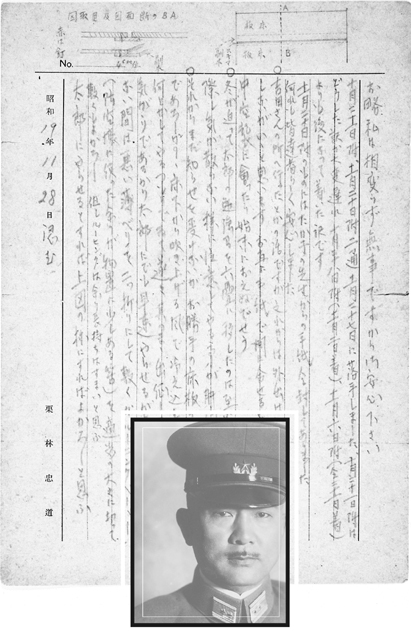

What Sadaoka Nobuyoshi had recited were the opening lines of the farewell telegram Lieutenant General Kuribayashi dispatched to the Imperial General Headquarters on March 16, 1945, when defeat and death were staring him in the face.

Within the American military, the marines had a reputation as a wild bunch of toughs, but even for them Iwo Jima was a gruesome and terrifying battle variously described as the worst battle in history and a hell within hell. Confronted with his own imminent death, the commander in chief had composed his final dispatch in an attempt to let the world know how bravely his men had fought and died on that isolated island 1,250 kilometers south of Tokyo, so far away from home.

The battle of Iwo Jima was hopeless from the start.

A cursory look at the discrepancy in fighting power between the two sides makes clear that the Japanese did not stand a one-in-ten-thousand chance of winning. The Japanese force on the island had neither airplanes nor warships to support them.

The same was true for land-based fighting power. Against a Japanese force of around twenty thousand men, some sixty thousand American troops came ashore, and backing up those sixty thousand were a further one hundred thousand support troops. The defeat and destruction of the Japanese forces was self-evident; their only real aim was to hold out for as long as they could in an effort to delay the American invasion of the Japanese homeland.

Against such a background, Kuribayashi wanted to take the last chance he had to tell the world how his menmost of them conscripts in their thirties or older, many of whom had left wives and children at home to come to the fronthad fought so brave and yet so tragic a fight that even the gods would weepa Japanese expression meaning that neither the souls of the dead nor the gods of heaven or of earth would be able to remain unmoved.

Sadaoka was not one of those men.

I wanted to die together with his lordship. Who knows how desperately he wanted that fate as a young man of twenty-six? But it was not to be.

Sadaoka was not a soldier but a civilian working for the military. In other words, he worked for the army, but fighting was not one of his duties.

In 1941, three and a half years before the fall of Iwo Jima, Kuriba-yashi was chief of staff of the South China Expeditionary Force (23rd Army) in Canton (present-day Guangzhou in China), while Sadaoka was working in the tailoring section responsible for mending the clothing of the officers.

One day, another civilian employee who worked in administration under Kuribayashi came over. The chief of staff wants me to ask if any of you can make him a white shirt, he said. The tailoring section dealt with army uniforms, and most of what they did was mending. There was nobody able to tailor a dress shirt.