Published by

Delacorte Press

an imprint of Random House Childrens Books

a division of Random House, Inc.

1540 Broadway

New York, New York 10036

Copyright 2001 by James Bradley and Ron Powers

Maps created by Mary Craddock Hoffman

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the Publisher, except where permitted by law.

The trademark Delacorte Press is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office and in other countries.

Visit us on the Web! www.randomhouse.com/teens

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at

www.randomhouse.com/teachers

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bradley, James.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-97926-1

1. Iwo Jima, Battle of, 1945Pictorial worksJuvenile literature. 2. PhotographsHistory20th centuryJuvenile literature. 3. Rosenthal, Joe, 1911 Juvenile literature. 4. World War, 19391945PhotographyJuvenile literature. 5. MarinesUnited StatesBiographyJuvenile literature. 6. United States. Marine CorpsBiographyJuvenile literature. [1. Iwo Jima, Battle of, 1945. 2. World War, 19391945Campaigns.] I. Powers, Ron. II. French, Michael, 1944 III. Title.

D767.99.I9 B73 2001

940.5426dc21

00-050914

v3.1

Dedicated to the memory of

Belle Block, Kathryn Bradley, Irene Gagnon,

Nancy Hayes, Goldie Price, Martha Strank,

and all mothers who sent their boys to war

Listen to me, and follow my orders,

and Ill try to bring all of you

back safely to your mothers.

SERGEANT MIKE STRANK

CONTENTS

ONE

Sacred Ground

The only thing new in the world is the history you dont know.

Harry Truman

In the spring of 1998 six boys called to me from half a century ago on a distant mountain, and I went there. For a few days I set aside my comfortable lifemy business concerns, my life in Rye, New Yorkand made a pilgrimage to the other side of the world, to a tiny Japanese island in the Pacific Ocean called Iwo Jima.

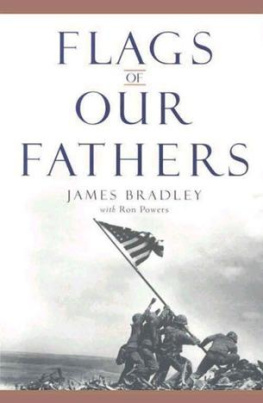

There, waiting for me, was the mountain the boys had climbed in the midst of a terrible battle half a century earlier. The Japanese called the mountain Suribachi, and on its battle-scarred summit the boys raised an American flag to symbolize our countrys conquest of that volcanic island, even though the fighting would rage for another month.

One of those flag raisers was my father.

The fate of the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries was being forged in blood on the island of Iwo Jima and others like it in the Pacific, as well as in North Africa, parts of Asia, and virtually all of Europe. The global conflict known as World War II had mostly teenagers as its soldierskids who had come of age in cultures that resembled those of the nineteenth century.

My father and his five comradesthey were either teenagers or in their early twentiestypified these kids: tired, scared, determined, brave. Like hundreds of thousands of other young men from many countries, they were trying to do their patriotic duty and trying to survive.

But something unusual happened to these six: History turned all its focus, for 1/400th of a second, on them. It froze them in an elegant instant of one of the bloodiest battles of the twentieth century, if not in the history of warfarefroze them in a camera lens as they hoisted an American flag on a makeshift iron pole.

Their collective image became one of the most recognized and most reproduced in the history of photography. It gave them a kind of immortalitya faceless immortality. The flag raising on Iwo Jima became a symbol of the island, the mountain, the battle; of World War II; of the highest ideals of the nation; of valor itself. It became everything except the salvation of the boys who performed it.

For these six, history had a different, special destiny that no one could have predicted, least of all the flag raisers themselves.

My father, John Henry Bradley, returned home to small-town Wisconsin after the war. He shoved the mementos of his immortality into a few cardboard boxes and hid these in a closet. He married his childhood sweetheart. He opened a funeral home, fathered eight children, joined the PTA, the Lions, and the Elksand shut out virtually any conversation on the topic of raising the flag on Iwo Jima.

When he died, in January 1994, in the town of his birth, he might have believed he was taking the story of his part in the flag raising with him to the grave, where he apparently felt it belonged. He had trained us, as children, to deflect the phone-call requests for media interviews that never diminished over the years. We were to tell the caller that our father was on a fishing trip, usually in Canada. But John Bradley never fished. No copy of the famous photograph hung in our house. When we did manage to extract from him a remark about the incident, his responses were short and simple, and he quickly changed the subject.

And this is how we Bradley children grew up: happily enough, deeply connected to our peaceful, tree-shaded town, but always with a sense of an unsolved mystery somewhere at the edges of the picture.

A middle child among the eight, I found the mystery tantalizing. I knew from an early age that my father had been some sort of hero. My third-grade schoolteacher said so; everybody said so. I hungered to know the heroic part of my dad. But try as I might, I could almost never get him to tell me about it.

John Bradley might have succeeded in taking his story to his grave had we not stumbled upon the cardboard boxes a few days after his death.

My mother and brothers Mark and Patrick were searching for my fathers will in the apartment he had maintained as his private office. In a dark closet they discovered three heavy cardboard boxes. In those boxes my father had saved the many photos and documents that came his way as a flag raiser. All of us were surprised that he had saved anything at all.

Later I rummaged through the boxes. One letter caught my eye. The cancellation indicated it was mailed from Iwo Jima on February 26, 1945, written by my father to his folks just three days after the flag raising: Id give my left arm for a good shower and a clean shave, I have a 6 day beard. Havent had any soap or water since I hit the beach. I never knew I could go without food, water or sleep for three days but I know now, it can be done.

And then, almost as an aside, he wrote: You know all about our battle out here. I was with the victorious [Company E,] who reached the top of Mt. Suribachi first. I had a little to do with raising the American flag and it was the happiest moment of my life.

The happiest moment of his life? What a shock! If it made him so happy, why didnt he ever talk about it? Did something happen either on Iwo Jima or in the intervening years to cause his silence?

Over the next few weeks I found myself staring at the photo on my office wall, daydreaming. Who were those boys with their hands on that pole? Were they like my father? Had they known one another before that moment or were they strangers united by a common duty? Was the flag raising the happiest moment of each of their lives?

The quest to answer those questions consumed four years of my life and ended, symbolically, with my own pilgrimage to Iwo Jima.