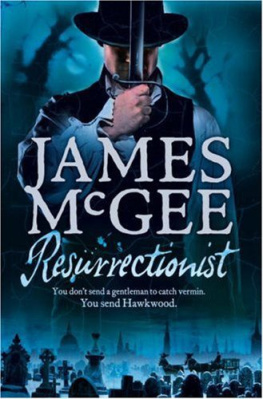

James Bradley - Resurrectionist, The

Here you can read online James Bradley - Resurrectionist, The full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2008, publisher: Faber and Faber Ltd, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Resurrectionist, The

- Author:

- Publisher:Faber and Faber Ltd

- Genre:

- Year:2008

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Resurrectionist, The: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Resurrectionist, The" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Resurrectionist, The — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Resurrectionist, The" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

We are born with the dead:

See, they return, and bring us with them.

T. S. Eliot, Four Quartets

London, 18267

I N THEIR SACKS they ride as in their mothers womb: knee to chest, head pressed down, as if to die is merely to return to the flesh from which we were born, and this a second conception. A rope behind the knees to hold them thus, another to bind their arms, then the mouth of the sack closed about them and bound again, the whole presenting a compact bundle, easily disguised, for to be seen abroad with such a cargo is to tempt the mob.

A knife then, to cut the rope which binds the sack, and, one lifting, the other pulling, we deliver it of its contents, slipping them forth onto the tables surface, naked and cold, as a calf or child stillborn slides from its mother. The knife again, to cut the rope which binds the body to itself, the sack and rope retained, for we shall use them again, much later, to dispose of the scraps and shreds.

Together then we take hold of them, forcing their bodies straight once more. Although their limbs do not loll, neither are they stiff, despite the chill that lingers in them, their rigor already broken by the graveside as they were bent and bound for sacking. Instead they shift beneath our grasp, moving with the peculiar malleability of a corpse caught midway between death and putrefaction. It is an ugly task, yet what ugliness it has lies not in the proximity of the dead but in the intimacy it demands of us, this closeness with the flesh and substance of their bodies.

When they are done, laid pale and naked on the table, we begin. First we turn them on their faces, exposing the flesh of the back and buttocks, mottled purple and green as if with bruises where the blood has pooled in the hours after death. If the flesh has begun to spoil there will be blisters forming soft, pale pouches of fluid which break when they are disturbed, but even if their flesh is sweet the skin will be moist with the liquid that seeps from them like sweat. Sometimes those who dressed them for the grave will have plugged their anuses, and if they have the obstruction must be removed and disposed of. Then, taking rags, and water, and vinegar, we begin the work of cleaning them, our hands moving carefully across their skin, the smell of the vinegar mingling with the darker scents that cling to them, the movements of our hands economical yet not without tenderness as we wipe and wring.

Once the back and legs are done we turn them over again, working from feet to groin, groin to chest, arms and hands, coming at last to the face. Here our work is most careful, cleaning around the bones and ridges with our folded rags, wiping the cheeks, the sunken pits of the eyes. Sometimes the lids will be open, caught in the stillness of death, the eyes beneath cloudy and colourless like the eyes of the very old, pale with cataracts.

The washing done we draw fresh water in the yard, fetch soap and razor. Cold water still, cold for the cold. Then, pulling the loose skin taut, we begin to shave; first the scalp and face, the hair coming away in wet clumps to expose the knobbled dome of the skull; then the chest and armpits; then finally the cold instruments of their sex, the blade of the razor rasping across their skin. Sometimes we will nick them as we work, but no blood comes, the wound pale and empty.

How we know this is work to be done in silence I cannot say. Only that this is how it is, how it must always be. At other times we move amongst them as if they were not there, talking and laughing as we lug and cut and tidy the pieces, pushing them aside as casually as we might a book or a jacket which lies where one means to sit. But here we work quietly, speaking no more than we must. It is as if this is a ritual, this washing of the dead: as one washes a baby clean of its mothers flesh, so we wipe the grave from these stolen dead, bring them new into the world.

When our work is finished the sacks are tidied away, the buckets emptied, the rags rinsed and left to dry, the books begun. Our master is most particular about the keeping of accounts, and the money paid to Caley and Walker must be noted: eight guineas for a man or woman fully grown, or what we call a large; four guineas for a child, or a small; a shilling by the inch for what we call a foetus, or a baby less than a foot in length. And so, while I mop the cellar floor Robert works quietly on the ledger, making notes of payments made, checking the balances against the contents of the cashbox, his face masked behind the look of quiet sadness he wears when he thinks he is unobserved.

Tonight there were three, two larges and a small, and by the time we are done, and we climb the stairs to the yard to wash our pails and hands at the butt, the sky has begun to lighten the high roofs which surround us. From far off there can be heard the ringing step of a horse upon the cobbles, but otherwise it is still, the air cold, the water from the pipe colder as we scrub our arms, over and over.

Mr Poll slips two fingers into the dead mans mouth, pulling the jaw open once more. Glancing up he surveys the watching students.

Death is a mirror, he says, in which life is reflected for our edification.

Beneath his fingers the dead mans tongue can be seen, purplish-grey like an oxens on a butchers slab, the darker mass of the tumour swollen beneath. Pressing down on it he tilts the head, staring in as if he has seen something that interests him. Then, his curiosity seemingly satisfied, he withdraws his fingers and pulls the lips back to expose the teeth, yellow and brown, higgledy-piggledy in the ulcerated flesh of the gums.

If death is a mirror, I find myself wondering, what lies behind it?

Finished with the mouth, he turns to Robert.

We will begin with the chest. The state of the vital organs must be ascertained.

A tremor runs through the body as the scalpel pierces the skin. Almost like a sigh, the gas that has swollen in the cavity is released, escaping in a soft breath. The smell is not quite foul, more the clinging scent of the butchers yard, that peculiarly clammy scent of cut meat intermingling with the first sweetness of putrefaction. I no longer choke on the smell, indeed there is scarcely a smell a body can produce which still turns my stomach, but although I do not gag I am aware of it, even after all these months.

The skin divides in a wake behind Mr Polls scalpel as he slices in one smooth motion from neck to groin. Carefully he makes more cuts at the top of the incision and at the bottom, then, with a practised motion, he pushes his fingers into the incision and peels back the skin, revealing the red flesh beneath, the white ribs and yellow fat.

Laying the two flaps of skin over the arms, he takes the saw Robert holds ready. Steadying himself with a hand upon the shoulder, he places the saw against the ribs and begins to cut. The teeth bite into the bone with a wet, splintering rasp, small flecks of meat and bone scattering before it, spattering the aprons we each of us wear. When he is done he lifts the sternum and ribs away, exposing the organs nestled in their broken cage of bone; grey, blue, black. Extending a hand he touches the heart, his thin fingers lingering upon the bluish muscle.

It does not beat, he says. The statement seems incontrovertible. But after a moment Mr Poll looks up, his watery blue eyes fixing me with their cold stare.

Why not?

I do not answer.

Do you think it a foolish question, Mr Swift?

I shake my head. No, sir, I say.

Perhaps you think its author a fool instead?

No, I say again.

Then why does it not beat? he asks once more, and as so often, I feel there is some simple thing expected, something which eluded me. Across the table I see Robert watching, his eyes steady.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Resurrectionist, The»

Look at similar books to Resurrectionist, The. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Resurrectionist, The and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.