Table of Contents

To all the quiet heroes following in Bradleys footsteps

INTRODUCTION

First Impressions

Northern Africa, February 23, 1943

The C-54 Skymaster ducked down from the clouds, its Pratt & Whitney radials pulling it toward the long, tan dagger jutting into the azure ocean ahead.

Africa.

As the plane dropped lower, green blotches appeared: trees spared the fury of the working bulldozers that razed the nearby land, turning it burnt yellow even as the aircraft dropped. A short, precariously narrow gray line appeared in the sand ahead. Ants were running near it.

Not ants, but men. Not a line, but a runwayunfinished. The men were laying steel planks to widen and extend it.

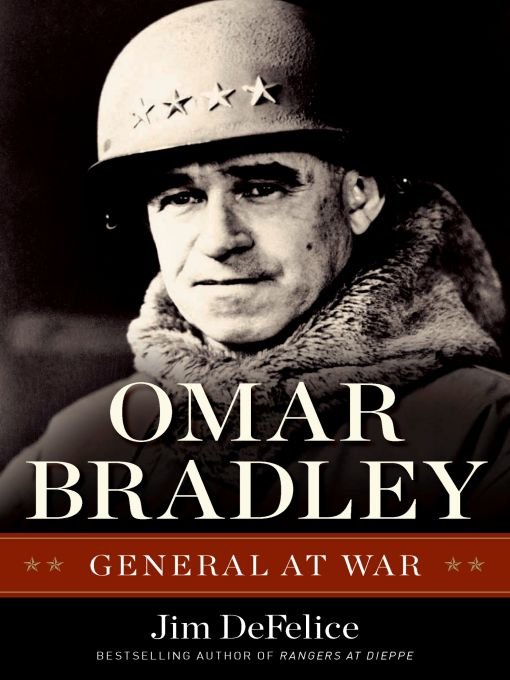

General Omar Bradley, stiff and tired from a flight that had begun the night before in Brazil, roused himself and gazed out the window.

Were landing, sir, said Chet Hansen, one of the generals two aides.

Bradley nodded. Taciturn, he continued to gaze out the window as the military transport bumped onto the steel grid, its wheels whining. A gust pushed the aircraft hard to the side as it landed; the Air Corps pilot mastered it, keeping the drab green airliner on the runway as he feathered the engines and went hard on the brakes. The short strip gave him little room for error.

The same might be said for the tens of thousands of Americans stretched out between the airport and the far-flung foothills of Tunisia well to the east. Three months before, the troops had landed in North Africa, full of hope and vigor, sure that they would bring the war against the Axis to a quick and victorious conclusion. Now they werent so sure. Their offensive had stalled badly. The reality of war had proven considerably more frightening than most had thought possible. Facing experienced German veterans, they had stumbled badly. Indeed, things were worse than most realized, as they had benefited from a good portion of luck at the start of the campaign, unnoticed as it may have been.

Luck had run out in a pass far to the east in Tunisia. There the young American force had been severely whipped in a mountainous area known as Kasserine Pass. At roughly the same time the C-54 was setting down, the architect of their defeat was repositioning his Panzers, threatening a strike that would break the young force entirely.

Bradley rose from his seat and made his way to the door with a mixture of anticipation, energy, and undoubtedly some apprehension. Though he was a general, hed never been this close to war before. Though he was regarded as a master tacticianand had instructed thousands in the arthis plans had never been put to the test of real combat. And though he was held in the highest esteem by men who had already proven themselves under fire, he himself had never heard an angry bullet crease the air nearby. At fifty, he was a virgin to combat.

This would not have mattered much if he was coming to take a staff job, or even if he intended only to fulfill the role of an observer, in theory the job he had been assigned. But Omar Nelson Bradley, while modest in speech and demeanor, had ambitions that extended beyond the job of advisor or assistant. He wanted desperately to lead men into battle. He wanted to win, and he wanted to kill.

Nor had the man who sent him across the Atlantic intended that he merely observe. U.S. Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall, whod known Bradley for years, believed he could help turn the faltering U.S. Army around. Originally opposed to the African campaign, Marshall had come to see it as a crucial test for the still inexperienced Army. It was a test that it had to pass, or it would suffer the most dire consequences.

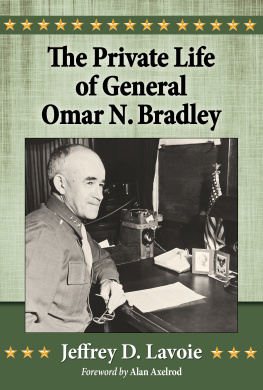

Most Americans, if theyve heard of Omar Bradley at all, know him from the 1970 movie Patton. Played by Karl Malden, Bradley there is a middle-aged, bespectacled milquetoast who couldnt organize a pickup softball game on his own. Disappearing into the woodwork whenever any real fighting needs to be done, Malden is the anti-Patton, a slouch-shouldered mouse incapable of roaring.

Ironically, Bradleywell into his seventies at that pointis credited as a consultant on the movie. Parts of his memoir, A Soldiers Story, formed the basis for the screenplay, which does track the historical events relatively accurately. Indeed, the screenplay itself casts Bradley in a fairly favorable, if clearly supporting, role. But anyone watching the movie cant be blamed if they end up wondering how exactly Omar Bradley came to lead the largest American military force ever assembled.

No one expects a movie to accurately portray history, but Bradley has fared just as poorly in many allegedly accurate histories as well. Called everything from a conservative infantryman to an unimaginative plodder, his designs for the war have been lost in a raft of misconceptions. His personality has been distorted until he appears the exact reverse of who he really was. His achievements have been handed to others, his failures magnified out of all proportion.

But perhaps the worst thing is that he has been forgotten or miscast even by serious historians. Bradley, even more than Eisenhower, the architect of the American victory in Europe, rarely appears in more than a cameo in many accounts focused on the campaign.

There are a number of reasons for this, but the most important is Bradley himself. He was, in a word, undramatic. And that has always been out of fashion in America.

By all accounts, Bradley was a man of moderate behavior, a mature leader who thought before he spoke, who risked his life but didnt call attention to it. He allowed his subordinates to take credit and glory. When he disagreed with his superiors, he did so discreetly. He dressed for the field, and looked it. He lived, for much of the war, in a truck.

Based on the testimony of his peers, Bradley was one of the great tacticians of the war, praised by everyone from paratroop commander James Gavin to Supreme Commander Dwight Eisenhower. But his real asset was his ability to get results from his commandershe was as much an enabler as a creator of success. The keys to this were his intelligence, his humanity, and most of all his ability to keep his ego largely in checka rare quality in a general of any rank, let alone one who ended his career with five stars.

That quality sprang directly from Bradleys character, forged in turn-of-the-century Midwestern America. Bradley was, first and last, a believer in values that, even during the War, would have been cynically termed small-townself-reliance, respect for others, humility. He was the product of an America that had only recently conquered the frontier, an America where brain and brawn fit together naturally. It was a time when being an athlete brought more responsibilities, not less, a place where a man hunted for food and worked out math problems for fun, an America where calling attention to ones achievements cheapened them irrevocably.

When so much of our perception of history depends on drama and flash, is there room for a man who personified quiet competence?

Yes. For beyond the flash and drama of the moment, the real achievements of the war depended on men like Bradley. And still do.