James Bradley - Flags of Our Fathers

Here you can read online James Bradley - Flags of Our Fathers full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2006, publisher: Random House Large Print, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Flags of Our Fathers

- Author:

- Publisher:Random House Large Print

- Genre:

- Year:2006

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Flags of Our Fathers: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Flags of Our Fathers" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Flags of Our Fathers — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Flags of Our Fathers" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

CONTENTS

DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF

Belle Block, Kathryn Bradley, Irene Gagnon,

Nancy Hayes, Goldie Price, Martha Strank,

and all mothers who sent their boys to war.

Mothers should negotiate between nations.

The mothers of the fighting countries would agree:

Stop this killing now. Stop it now.

YOSHIKUNI TAKI

One

The only thing new in the world is the history you dont know.

HARRY TRUMAN

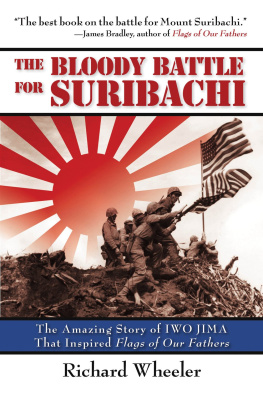

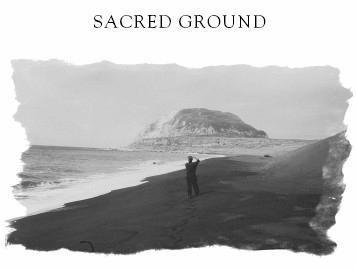

IN THE SPRING OF 1998, six boys called to me from half a century ago on a distant mountain and I went there. For a few days I set aside my comfortable lifemy business concerns, my life in Rye, New Yorkand made a pilgrimage to the other side of the world, to a primitive flyspeck island in the Pacific. There, waiting for me, was the mountain the boys had climbed in the midst of a terrible battle half a century earlier. One of them was my father. The mountain was called Suribachi; the island, Iwo Jima.

The fate of the late-twentieth and twenty-first centuries was being forged in blood on that island and others like it. The combatants, on either side, were kidskids who had mostly come of age in cultures that resembled those of the nineteenth century. My young father and his five comrades were typical of these kids. Tired, scared, thirsty, brave; tiny integers in the vast confusion of war-making, trying to do their duty, trying to survive.

But something unusual happened to these six: History turned all its focus, for 1/400th of a second, on them. It froze them in an elegant instant of battle: froze them in a camera lens as they hoisted an American flag on a makeshift pole. Their collective image, blurred and indistinct yet unforgettable, became the most recognized, the most reproduced, in the history of photography. It gave them a kind of immortalitya faceless immortality. The flagraising on Iwo Jima became a symbol of the island, the mountain, the battle; of World War II; of the highest ideals of the nation, of valor incarnate. It became everything except the salvation of the boys who formed it.

For these six, history had a different set of agendas.

Three were killed in action in the continuing battle. Of the three survivors, two were overtaken and eventually destroyeddead of drink and heartbreak. Only one of them managed to live in peace into an advanced age. He achieved this peace by willing the past into a cave of silence.

My father, John Henry Bradley, returned home to small-town Wisconsin after the war. He shoved the mementos of his immortality into a few cardboard boxes and hid these in a closet. He married his third-grade sweetheart. He opened a funeral home; fathered eight children; joined the PTA, the Lions, the Elks; and shut out any conversation on the topic of raising the flag on Iwo Jima.

When he died in January 1994, in the town of his birth, he might have believed he was taking the unwanted story of his part in the flagraising with him to the grave, where he apparently felt it belonged. He had trained us, as children, to deflect the phone-call requests for media interviews that never diminished over the years. We were to tell the caller that our father was on a fishing trip. But John Bradley never fished. No copy of the famous photograph hung in our house. When we did manage to extract from him a remark about the incident, his responses were short and simple and he quickly changed the subject.

And this is how we Bradley children grew up: happily enough, deeply connected to our peaceful, tree-shaded town, but always with a sense of an unsolved mystery somewhere at the edges of the picture. We sensed that the outside world knew something important about him that we would never know. For him, it was a dead issue; a boring topic. But not for the rest of us. Me, especially.

For me, a middle child among the eight, the mystery was tantalizing. I knew from an early age that my father had been some sort of hero. My third-grade schoolteacher said so; everybody said so. I hungered to know the heroic part of my dad. But try as I might I could never get him to tell me about it.

The real heroes of Iwo Jima, he said once, coming as close as he ever would, are the guys who didnt come back.

John Bradley might have succeeded in taking his story to his grave had we not stumbled upon the cardboard boxes a few days after his death.

My mother and brothers Mark and Patrick were searching for my fathers will in the apartment he had maintained as his private office. In a dark closet they discovered three heavy cardboard boxes, old but in good shape, stacked on top of each other.

In those boxes my father had saved the many photos and documents that came his way as a flagraiser. All of us were surprised that he had saved anything at all.

Later I rummaged through the boxes. One letter caught my eye. The cancellation indicated it was mailed from Iwo Jima on February 26, 1945. A letter written by my father to his folks just three days after the flagraising.

The carefree, reassuring style of his sentences offers no hint of the hell he had just been through. He managed to sound as though he were on a rugged but enjoyable Boy Scout hike: Id give my left arm for a good shower and a clean shave, I have a 6 day beard. Havent had any soap or water since I hit the beach. I never knew I could go without food, water or sleep for three days but I know now, it can be done.

And then, almost as an aside, he wrote: You know all about our battle out here. I was with the victorious [Easy Company] who reached the top of Mt. Suribachi first. I had a little to do with raising the American flag and it was the happiest moment of my life.

The happiest moment of his life! What a shock to read that. I wept as I realized the flagraising had been a happy moment for him as a twenty-one-year-old. What happened in the intervening years to cause his silence?

Reading my fathers letter made the flagraising photo somehow come alive in my imagination. Over the next few weeks I found myself staring at the photo on my office wall, daydreaming. Who were those boys with their hands on that pole? I wondered. Were they like my father? Had they known one another before that moment or were they strangers, united by a common duty? Did they joke with one another? Did they have nicknames? Was the flagraising the happiest moment of each of their lives?

The quest to answer those questions consumed four years. At its outset I could not have told you if there were five or six flagraisers in that photograph. Certainly I did not know the names of the three who died during the battle.

By its conclusion, I knew each of them like I know my brothers, like I know my high-school chums. And I had grown to love them.

What I discovered on that quest forms the content of this book.

The quest ended, symbolically, with my own pilgrimage to Iwo Jima. Accompanied by my seventy-four-year-old mother, three of my brothers, and many military men and women, I ascended the 550-foot volcanic crater that was Mount Suribachi. My twenty-one-year-old father had made the climb on foot carrying bandages and medical supplies; our party was whisked up in Marine Corps vans. I stood at its summit in a whipping wind that helped dry my tears. This was exactly where that American flag was raised on a February afternoon fifty-three years before. The wind had whipped on that day as well. It had straightened the rippling fabric of that flag by its force.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Flags of Our Fathers»

Look at similar books to Flags of Our Fathers. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Flags of Our Fathers and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.