Table of Contents

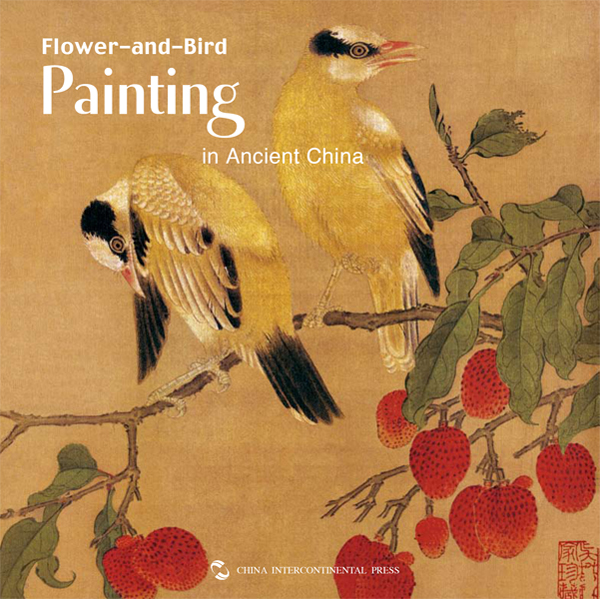

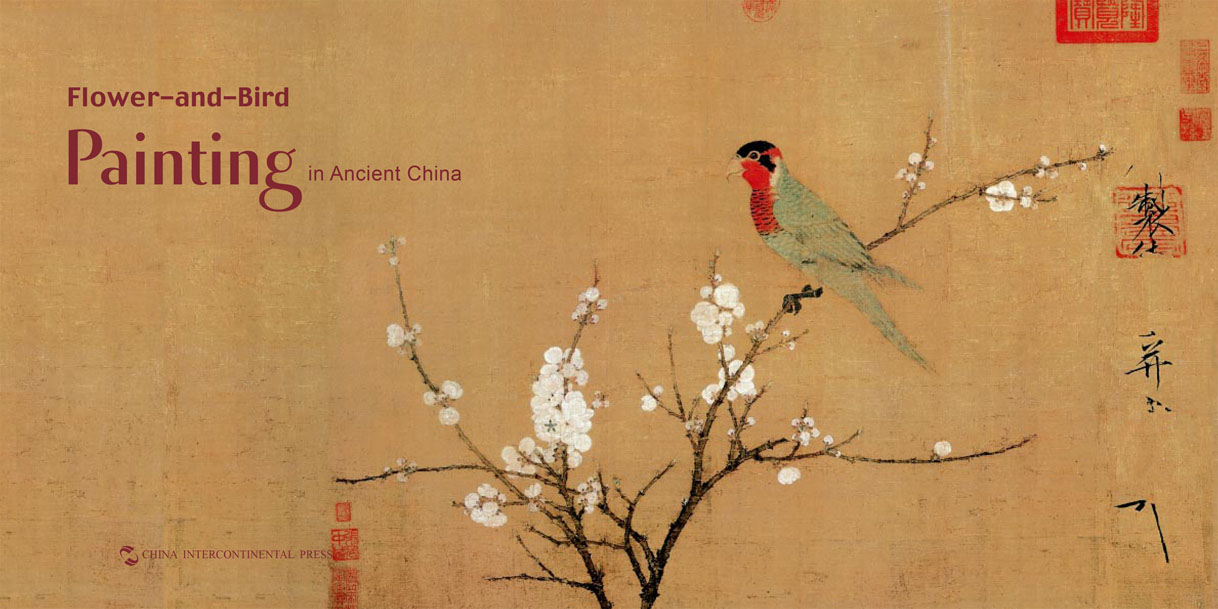

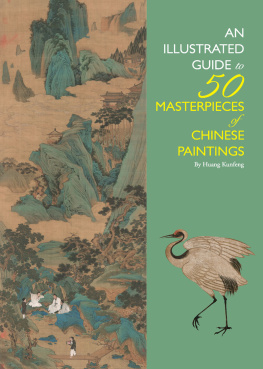

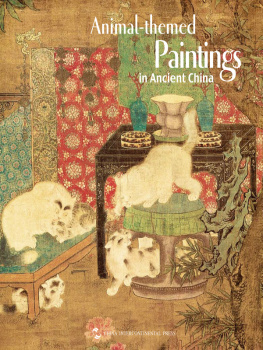

Preface The Chinese ancestors who invented the original pictographic Chinese characters also developed, with the passage of time, the unique traditional Chinese painting, which falls into three genres: flower-and-bird, landscape and figure drawing. The flower-and-bird painting traces its history back to ancient times. It embraced many different schools and a large number of accomplished painters came to the fore. Archaeological data show that in the Neolithic Age, people already used "brushes" and natural pigments to draw flowers, birds and fish on pottery, which can be regarded as the embryo of China's flower-and-bird painting. Abstract birds and animals were engraved on bronze ware of the Shang (1600-1046 BC) and Zhou (1046-256 BC) dynasties. Archaeologists also found phoenixes drawn on silk belonging to the Warring States Period (475-221 BC) and zhuque (similar to phoenix, referring to the seven southern mansions of the 28 lunar mansions in ancient astronomy) on silk and lacquer ware of the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 25).

As late as the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220) appeared relatively mature flower-and-bird paintings. According to historical materials, during the Wei Kingdom (220-265), Jin Dynasty (265-420), Northern and Southern Dynasties (386-589) some painters began to specialize in flower-and-bird painting, marking that divorced from figure and landscape drawing, it entered Chinese art as an independent genre. The Tang Dynasty (618-907) was a period in which the new genre reached maturity. With their technique being perfected day by day, more professional painters were expert at drawing flowers and birds. Both the Five Dynasties (907-960) and the Yuan Dynasty (1206-1368) saw further improvement of flower-and-bird painting, which entered its heyday actually in the sandwiched Song Dynasty (960-1279). The two dynasties of Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1616-1911) produced numerous flower-and-bird masters, making the genre known to the Western world.

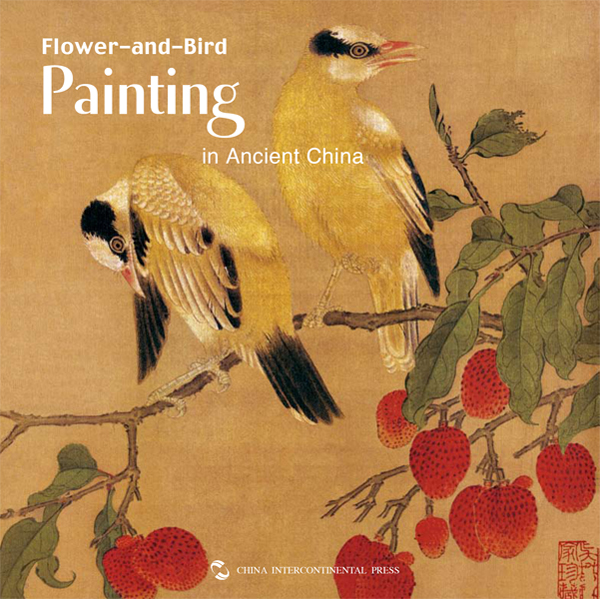

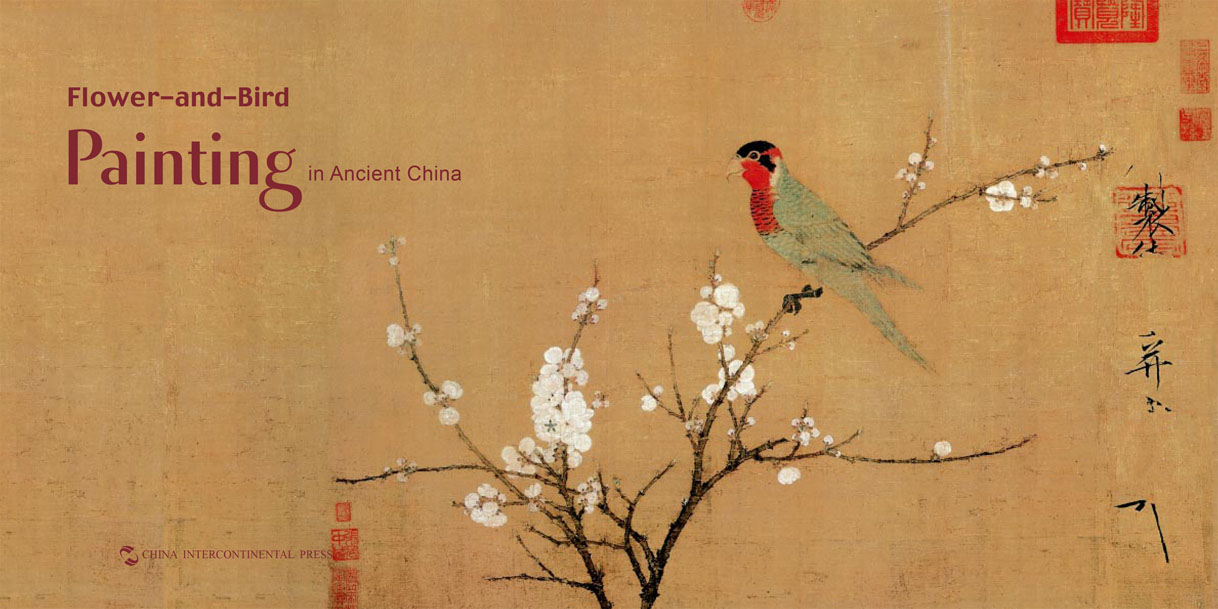

Those painters depicted a great variety of subjects, including flowers, plants, birds, beasts, vegetables, fruits, mountain rocks, and fish, to express their feelings and understanding of nature. In this way, flower-and-bird painting can be rated as a perfect combination of traditional Chinese culture and art. Many subjects, known very well by the public, have commonly accepted implications. For instance, the peony stands for wealth and rank, orchid for elegance, lotus for self-preservation and moral integrity, chrysanthemum for honor in one's later years, plum for innate pride and iron determination, bamboo for tenacity and indomitableness, pomegranate for fertility, pine and crane for longevity, mandarin ducks for love, fish for abundance, and so on. These exquisite paintings are highly aesthetic, with many being kept by private collectors and museums at home and abroad. Some have become China's national treasures.

The technique of drawing ranges from gong-bi (fine, delicate brushwork), xie-yi (freehand brushwork) to the combination of the two. The paintings are mainly drawn on silk or paper in the form of horizontal scroll, vertically-hung scroll, album and fan. In terms of the use of color, there are five methods: colored painting, linedrawing, shui-mo painting (ink and wash), po-mo painting (splash-ink), and mo-gu or "boneless" painting (drawing without outline but with forms achieved by washes of ink and color). Many drawing skills like shui-mo , po-mo and mo-gu were created distinctively by Chinese painters, making flower-and-bird painting a unique art-form in the world. China's traditional flower-and-bird painting and Western painting have both similarities and differences.  Classical Western still-life painting gives priority to accurately reproducing an object's original shape.

Classical Western still-life painting gives priority to accurately reproducing an object's original shape.

In other words, a sense of visual accuracy is prerequisite to judging a painter's skill and understanding his or her aesthetic conception. The works of Chinese painters cover a relatively wider range of subjects. They paid more attention to the creation of yi-jing (artistic mood). Therefore, they sought after similarity in spirit rather than formal resemblance, and underscored the integrity and harmony of a tableau. As a result, the viewers can often feel a particular charm and appeal from these paintings.  Flower-and-bird Paintings of the Five Dynasties

Flower-and-bird Paintings of the Five Dynasties

and the Two Song Dynasties Very few flower-and-bird paintings made before the 10th century have been handed down to this very day.

Flower-and-bird painting entered into a stage of great innovation and rapid development during the Five Dynasties (907-960) with the technique of drawing gradually attaining to perfection. Meanwhile, various schools with distinctive styles and features appeared. One was represented by Huang Quan (903-965), another by Xu Xi (937-975). Huang had served as an imperial painter for many years. Drawing materials from exotic flowers and herbs, rare birds and animals that were planted and raised in the imperial gardens and palaces, his paintings were characterized by meticulous depiction and bright colors, and acclaimed as Huang jia fu gui (the Huang school's characteristic magnificence). Though coming from a prominent family, Xu had never entered into officialdom.

Actually, either flowers, plants, vegetables, fruits and insects in gardens or water birds and fish in brooks were worthy of his brush. His paintings full of idyllic taste thus produced a fresh artistic conception, and his style was called Xu Xi ye yi (Xu Xi's unconventional, original charm). The two schools have had an immense influence upon flower-and-bird painting of later ages. The drawing technique of Huang Quan was inherited by his sons Huang Jucai (933-?) and Huang Jubao (whose dates of birth and death are unknown), and developed into the well-known "Huang Style." Xu Xi's followers included his grandsons Xu Chongsi and Xu Chongju, who were both famous flowerand-bird painters in the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127). China's flower-and-bird painting enjoyed its first heyday in the Northern and Southern Song dynasties, during which the practice of establishing an Imperial Art Academy in the Five Dynasties was still in use. Following in the footsteps of their Five Dynasties predecessors, painters of the Northern Song Dynasty paid more attention to sketching, with their brushwork becoming finer and smoother.

The championship and participation of Emperor Huizong (1082-1135) further boosted the creation of flower-and-bird painting. Artists of the entire country gathered in the imperial palace, and scored unprecedented successes. The imperial-court decorative painting featuring delicate, exquisite strokes gradually attained to maturity; and what's more, both freehand brushwork painting and literati painting began to come to the fore at that time. The former portrays objects in ink and wash with succinct, bold strokes, and produces an effect of running ink by means of the Xuan paper (high-quality rice paper made in east China's Anhui Province); while the latter themed withered trees, bamboos, rocks, orchids and plums expresses the temperament and taste of literary scholars, which is very different from what's seen in the works of imperial and folk artists. Besides those living through the Five Dynasties and the Northern Song Dynasty like Huang Jucai, Huang Jubao, Xu Chongsi and Xu Chongju, important flower-and-bird painters of this period (the two Song dynasties) included Zhao Chang, Wu Bing, Ma Lin, Wen Tong, Emperor Huizong, Cui Bai, Bian Luan, Li Di, Yang Wujiu, Zhao Mengjian and Liang Kai.

![Flower - China: [the essential guide to customs & culture]](/uploads/posts/book/200771/thumbs/flower-china-the-essential-guide-to-customs.jpg)

Preface The Chinese ancestors who invented the original pictographic Chinese characters also developed, with the passage of time, the unique traditional Chinese painting, which falls into three genres: flower-and-bird, landscape and figure drawing. The flower-and-bird painting traces its history back to ancient times. It embraced many different schools and a large number of accomplished painters came to the fore. Archaeological data show that in the Neolithic Age, people already used "brushes" and natural pigments to draw flowers, birds and fish on pottery, which can be regarded as the embryo of China's flower-and-bird painting. Abstract birds and animals were engraved on bronze ware of the Shang (1600-1046 BC) and Zhou (1046-256 BC) dynasties. Archaeologists also found phoenixes drawn on silk belonging to the Warring States Period (475-221 BC) and zhuque (similar to phoenix, referring to the seven southern mansions of the 28 lunar mansions in ancient astronomy) on silk and lacquer ware of the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 25).

Preface The Chinese ancestors who invented the original pictographic Chinese characters also developed, with the passage of time, the unique traditional Chinese painting, which falls into three genres: flower-and-bird, landscape and figure drawing. The flower-and-bird painting traces its history back to ancient times. It embraced many different schools and a large number of accomplished painters came to the fore. Archaeological data show that in the Neolithic Age, people already used "brushes" and natural pigments to draw flowers, birds and fish on pottery, which can be regarded as the embryo of China's flower-and-bird painting. Abstract birds and animals were engraved on bronze ware of the Shang (1600-1046 BC) and Zhou (1046-256 BC) dynasties. Archaeologists also found phoenixes drawn on silk belonging to the Warring States Period (475-221 BC) and zhuque (similar to phoenix, referring to the seven southern mansions of the 28 lunar mansions in ancient astronomy) on silk and lacquer ware of the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 25).  Classical Western still-life painting gives priority to accurately reproducing an object's original shape.

Classical Western still-life painting gives priority to accurately reproducing an object's original shape. Flower-and-bird Paintings of the Five Dynasties

Flower-and-bird Paintings of the Five Dynasties