Unlike beer and wine, which have been traced back to the earliest prehistoric agricultural cultures, the distillation of spirits is a comparatively recent invention. Even so, archaeology has traced it back to at least 3,000 years BC and perhaps even earlier in Asia. The science of distillation from the Latin phrase destillare, to distil by boiling and drawing off the alcoholic vapour by drips began as a medicinal process. Liquids fermented from fruit, plant or grain were boiled or burnt to produce a concentrate of their alcoholic content for a medical, ritual or even magical application. Only later were these potions and filtres seen to have the recreational effect which we appreciate today.

Distillation itself is the separation of sugar alcohols by vaporization. A fruit, vegetable or grain wash is heated in a retort or alembic (a sealed container) to the point where the alcohol content becomes steam. The retort or alembic, usually metal, filters the alcohol content into a secondary vessel. Pure alcohol is the product of the distilling process. There is also an alternative form of distilling, once favoured by early vodka producers and makers of applejack, the American variant of French calvados, of freezing the wash to separate the alcohol from the water, although this is rarely if ever used these days.

All spirits share the same base: ethanol or ethyl alcohol, or pure alcohol. Alcohol derives from the Arabic al-kuhl and may be described as a flammable liquid explosive with the chemical formula CHOH. This base (known as silent or quiet alcohol) is a water of life, known variously as eau de vie, akva vit, aqua vitae or, in the case of the original Gaelic term for whisky, uisce (or uisge) beatha.

The distinctive flavours and colours of the spirit families derive from the processes involved in making drinks such as gin, rum, vodka or whiskey (all non-Scots brands are spelt whiskey). Gin, or Dutch jenever, is produced from raw alcohol and botanicals, which are vegetable flavourings, chiefly juniper berries. Rum is distilled from sugar cane. Vodka is distilled from grain or, sometimes, potatoes. Some argue that gin and vodka are, essentially, from the same family, while whisky derives its flavours from fermented barley and spring water, ageing in oak vats and blending. In each case, the pure, distilled alcohol is diluted with water for bottling or blending to reduce its alcoholic potency.

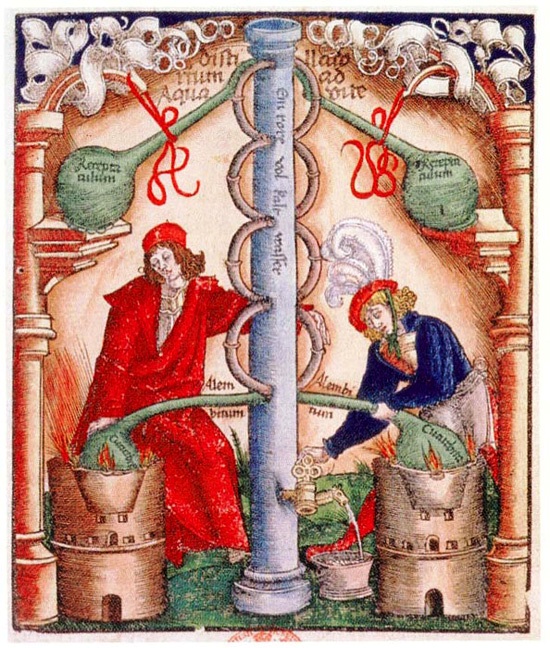

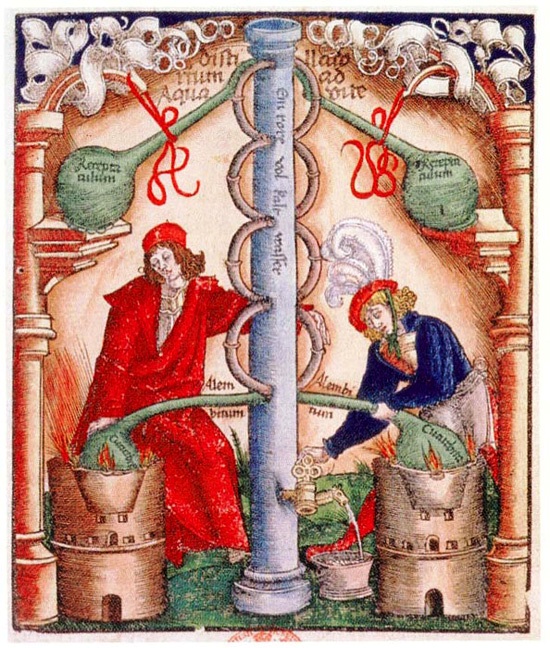

Title page from A Manual for Distillers, published in 1519

While the earliest forms of distillation were chiefly for medicinal or cosmetic uses, it is believed that whiskey was being made in Ireland as long ago as the sixth century AD. It is thought that missionaries from Irish monasteries had a hand in spreading knowledge of distilling technology throughout Europe in the eleventh century. The Arabic world is credited with the invention of the alembic and introducing it into Spain, Sicily and other conquered territories. It seems that distilling spread north from the Mediterranean: brandies were being produced in France from at least the twelfth century onwards, and akva vits in Holland from the fourteenth. By the sixteenth century, distilling as far north as Finland and as far east as Russia was common. Distilling science sailed for America with the first European settlers in the sixteenth century.

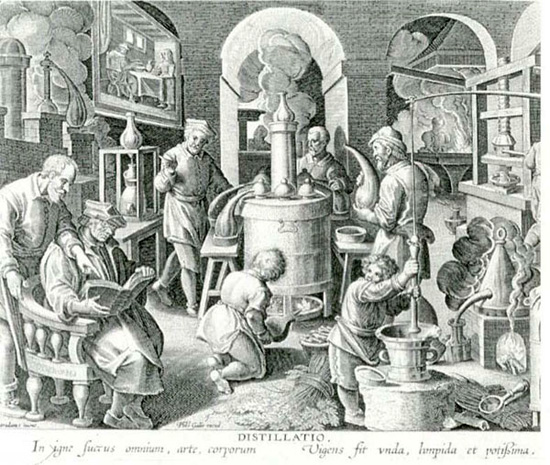

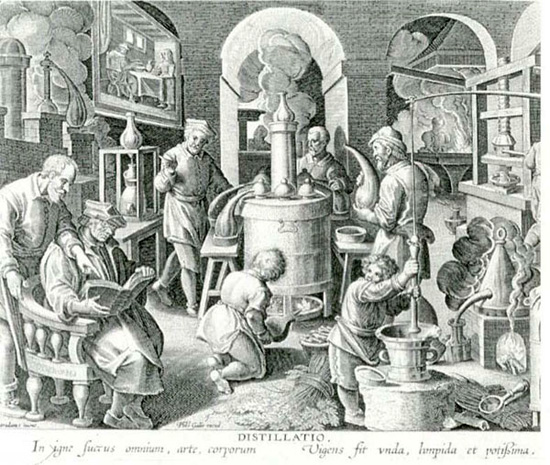

16th century engraving showing the distillation process

However, it was only in the seventeenth century that the produce of distillation began to be enjoyed as a tipple. Until then, it was still used chiefly as a medicinal tonic. The fourteenth-century bubonic plague known as the Black Death, which is estimated to have killed 50 million people across Europe, is thought to have helped popularize the medicinal use of alcohol through the widespread use of fruit cordials laced with strong alcohol. While such potions had no curative effect, they at least acted as painkillers.

Alcoholic beverages, usually brandy, were being used for medicinal purposes as late as the 1860s, with patients being prescribed a litre (1 pints) or more of brandy a day. Prince Albert is believed to have been one such patient, who probably died of the cure rather than cause of his illness. It was only towards the end of the nineteenth century, with the advent of modern drugs and methods of measuring their effect, that the myth of the curative powers of alcohol began to wane.

The Highlands of Scotland

From the historical information accessible to us, it would seem that whisky was one of the earliest forms of aqua vitae, produced first in Ireland, probably by monks. In the sixth century, distilling techniques would have been extremely crude. One history even suggests that the origin of the drink lies in the need to use barley which had been rendered useless for culinary purposes by a wet harvest. The barley would have been placed in a sack and left in a spring for two or three days to promote sprouting, and then laid out to dry for ten days to allow sprouting to commence. Sprouting would have been halted by drying the barley in a rudimentary kiln or drying shed. The barley would then be mixed with yeast and boiled. Collected and allowed to cool, the vapour from the process would be a raw and fiery primitive form of malt whiskey. When the process was introduced into Scotland, the barley would be dried over peat fires, the peat giving the liquor a distinctive, earthy flavour.

For centuries, the most common form of still, or distilling apparatus was the pot still, a large, sealed kettle which tapered at the top to funnel vaporized alcohol from the boiling wash into a pipe leading down from the top of the still. Later developments would take the downpipe through cold water to speed up condensation and collection of the alcohol. Even later, distillers would discover the cleansing qualities of copper, which neutralizes impurities in the alcohol. However, the pot still did not lend itself to the production of large quantities of alcohol. After each batch, the still had to be allowed to cool, cleared of dregs and then prepared to boil the next batch of liquor.

A modern pot stillroom at Yamazaki Distillery, Japan

In 1826, Robert Stein, a relative of the Haig whisky family, invented the patent for the continuous still, which improved on the pot still by passing the heated wash through an analyser. This vaporized the alcohol and carried it into a rectifier, which cooled and collected the alcohol product. The continuous still was able to handle large quantities of the wash, and had the additional benefit of sumps, which drew off spent wash and steam. The continuous still made it possible to produce a quiet or silent alcohol from grain which had not been malted (i.e. baked), in greater quantities, and much more quickly than before. A lighter, less pungent grain whisky was the result. Within a decade, however, Steins model was superseded by the Coffey still, invented by Aeneas Coffey, former Inspector-General of Irish Excise in Dublin.