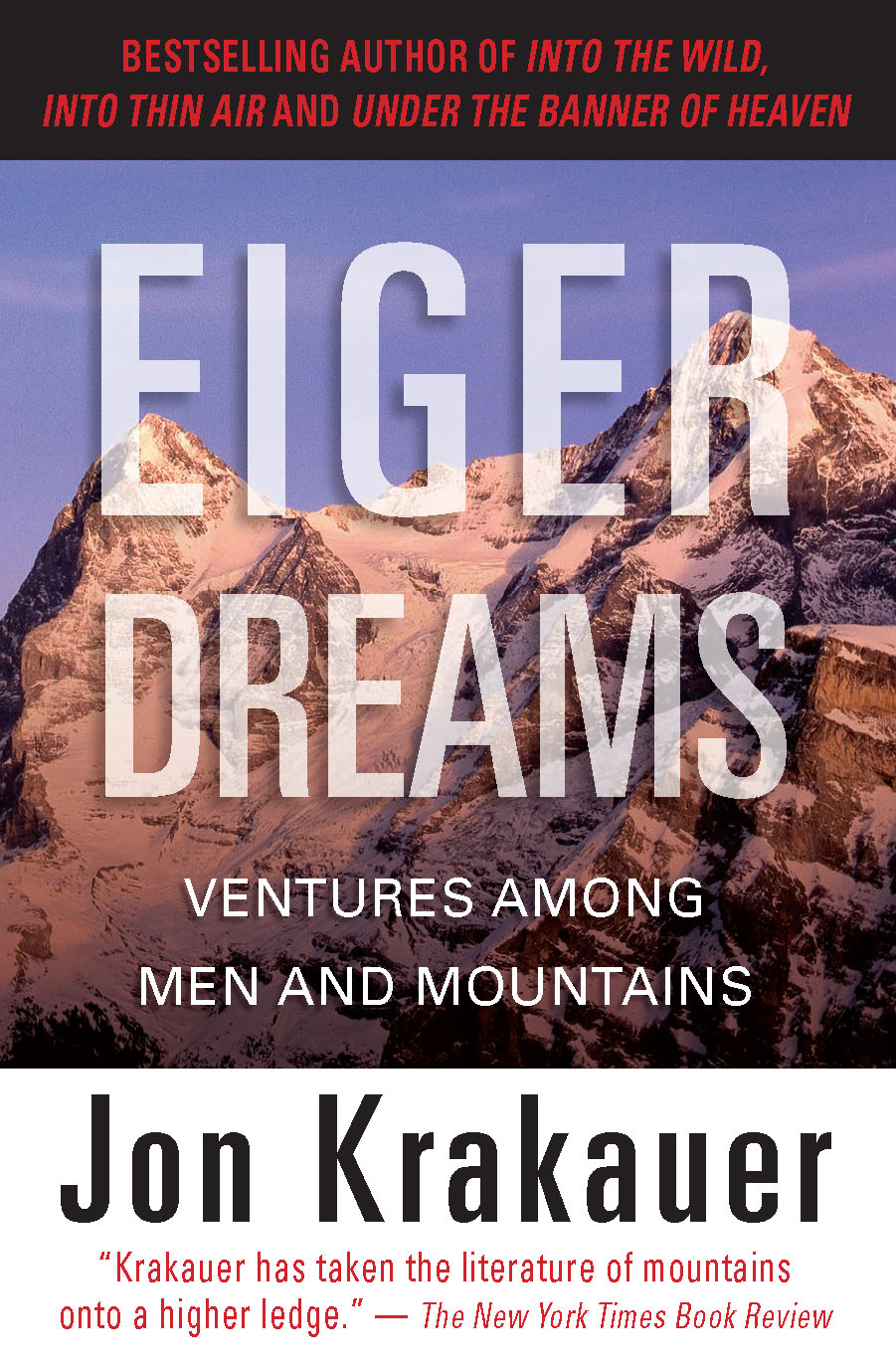

EIGER DREAMS

EIGER DREAMS

Ventures Among Men and Mountains

Jon Krakauer

THE LYONS PRESS

Guilford, Connecticut

An imprint of The Globe Pequot Press

Copyright 1990, 2009 by Jon Krakauer

Previously published by Lyons & Burford in 1990.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to The Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, P.O. Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

The Lyons Press is an imprint of The Globe Pequot Press.

Portions of this book have appeared previously: Eiger Dreams, in Outside , March 1985; Gill, in New Age Journal, March 1985; Valdez Ice, in Smithsonian, January 1988; On Being Tentbound, in Outside, October 1982; The Flyboys of Talkeetna, in Smithsonian, January 1989; Club Denali, in Outside, December 1987; Chamonix, in Outside, July 1989; Canyoneering, in Outside, October 1988; A Mountain Higher than Everest? in Smithsonian, October 1987; The Burgess Boys, in Outside, August 1988; A Bad Summer on K2, in Outside, March 1987 (cowritten with Greg Child).

Text design and layout: Kim Burdick

Project manager: John Burbidge

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Krakauer, Jon.

Eiger dreams : adventures among men and mountains / Jon Krakauer.

p. cm.

Originally published: New York : Lyons & Burford, 1990.

E-ISBN 978-0-7627-9606-9

1. Mountaineering. I. Title.

GV200.K73 2009

796.522dc22

2008046742

For LINDA, with thoughts of Green Mountain Falls, the Wind Rivers, and Roanoke Street.

The oldest, most widespread stories in the world are adventure stories, about human heroes who venture into the myth-countries at the risk of their lives, and bring back tales of the world beyond men... It could be argued... that the narrative art itself arose from the need to tell an adventure; that man risking his life in perilous encounters constitutes the original definition of what is worth talking about.

Paul Zweig

The Adventurer

Having an adventure shows that someone is incompetent, that something has gone wrong. An adventure is interesting enough in retrospect, especially to the person who didnt have it; at the time it happens it usually constitutes an exceedingly disagreeable experience.

Vilhjalmur Stefansson

My Life with the Eskimo

CONTENTS

AUTHORS NOTE

M OUNTAIN CLIMBING IS comprehended dimly, if at all, by most of the nonclimbing world. Its a favorite subject for bad movies and spurious metaphors. A dream about scaling some high, jagged alp is something a shrink can really sink his teeth into. The activity is wrapped in tales of audacity and disaster that make other sports out to be trivial games by comparison; as an idea, climbing strikes that chord in the public imagination most often associated with sharks and killer bees.

It is the aim of this book to prune away some of this overgrown mystiqueto let in a little light. Most climbers arent in fact deranged, theyre just infected with a particularly virulent strain of the Human Condition.

In the interest of truth in packaging, I should state straightaway that nowhere does this book come right out and address the central questionWhy would a normal person want to do this stuff?head on; I circle the issue continually, poke at it from behind with a long stick now and then, but at no point do I jump right in the cage and wrestle with the beast directly, mano a mano . Even so, by the end of the book I think the reader will have a better sense not only of why climbers climb, but why they tend to be so goddamn obsessive about it.

I trace the roots of my own obsession back to 1962. I was a fairly ordinary kid growing up in Corvallis, Oregon. My father was a sensible, rigid parent who constantly badgered his five children to study calculus and Latin, keep their noses to the grindstone, fix their sights early and unflinchingly on careers in medicine or law. Inexplicably, on the occasion of my eighth birthday this strict taskmaster presented me with a pint-size ice axe and took me on my first climb. In retrospect I cant imagine what the old man was thinking; if hed given me a Harley and a membership in the Hells Angels he couldnt have sabotaged his paternal aspirations any more effectively.

By the age of eighteen climbing was the only thing I cared about: work, school, friendships, career plans, sex, sleepall were made to fit around my climbing or, more often, neglected outright. In 1974 my preoccupation intensified further still. The pivotal event was my first Alaskan expedition, a month-long trip with six companions to the Arrigetch Peaks, a knot of slender granite towers possessed of a severe, haunting beauty. One June morning at 2:30 a.m. , after climbing for twelve straight hours, I pulled up onto the summit of a mountain called Xanadu. The top was a disconcertingly narrow fin of rock, likely the highest point in the whole range. And ours were the first boots ever to step upon it. Far below, the spires and slabs of the surrounding peaks glowed orange, as if lit from within, in the eerie, nightlong dusk of the arctic summer. A bitter wind screamed across the tundra from the Beaufort Sea, turning my hands to wood. I was as happy as Id ever been in my life.

I graduated from college, by the skin of my teeth, in December, 1975. I spend the next eight years employed as an itinerant carpenter and commercial fisherman in Colorado, Seattle, and Alaska, living in studio apartments with cinder-block walls, driving a hundred-dollar car, working just enough to make rent and fund the next climbing trip. Eventually it began to wear thin. I found myself lying awake nights reliving all the close scrapes Id had on the heights. Sawing joists in the rain at some muddy construction site, my thoughts would increasingly turn to college classmates who were raising families, investing in real estate, buying lawn furniture, assiduously amassing wealth.

I resolved to quit climbing, and said as much to the woman with whom I was involved at the time. She was so taken aback by this announcement that she agreed to marry me. Id grossly underestimated the hold climbing had on me, however; giving it up proved much more difficult than Id imagined. My abstinence lasted barely a year, and when it ended it looked for a while like the connubial arrangement was going to end with it. Against all odds, I somehow managed to stay married and keep climbing. No longer, however, did I feel compelled to push things right to the brink, to see God on every pitch, to make each climb more radical than the last. Today I feel like an alcoholic whos managed to make the switch from week-long whiskey benders to a few beers on Saturday night. Ive slipped happily into alpine mediocrity.

My ambitions as a climber have been inversely proportional to my efforts as a writer. In 1981, I sold my first article to a national magazine; in November, 1983, I bought a word processor, took off my tool belt for what I hoped would be the last time, and began writing for a living. Ive been at it full-time ever since. These days more and more of my assignments seem to be about architecture, or natural history, or popular cultureIve written about fire walking for Rolling Stone , wigs for Smithsonian , neo-Rgency design for Architectural Digest but mountaineering stories continue to be nearest and dearest to my heart.