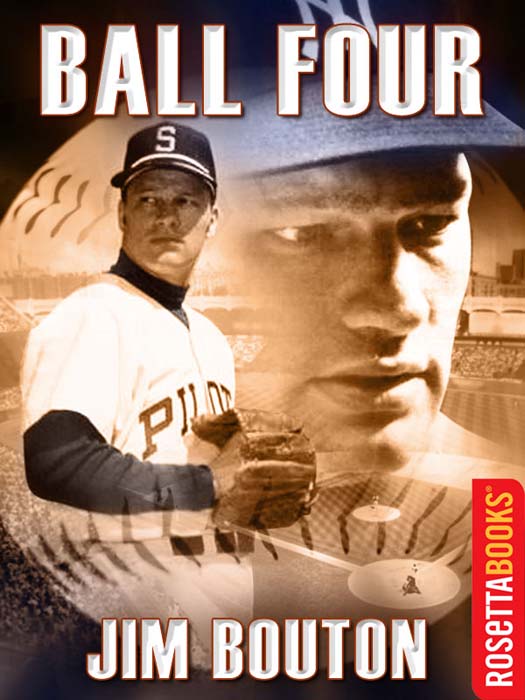

Ball Four

The Final Pitch

Jim Bouton

Copyright

Ball Four

Copyright 1970, 1981, 1990, 2000 by Jim Bouton

Cover art to the electronic edition copyright 2012 by RosettaBooks, LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Electronic edition published 2012 by RosettaBooks LLC, New York.

ISBN e-Pub edition: 9780795323249

For more information about Jim Bouton and Foul Ball, visit www.JimBouton.com.

DEDICATION

For Laurie

Contents

Ball Four

Ball Five

Ball Six

Ball Seven

PREFACE

WRITTEN IN 1980; UPDATED IN 1990 AND 2000.

There was a time, not too long ago, when school kids read Ball Four at night under the covers with a flashlight because their parents wouldnt allow it in the house. It was not your typical sports book about the importance of clean living and inspired coaching. I was called a Judas and a Benedict Arnold for having written it. The book was attacked in the media because among other things, it used four-letter words and destroyed heroes. It was even banned in a few libraries because it was said to be bad for the youth of America.

The kids, however, saw it differently. I know because they tell me about it now whenever I lecture on college campuses. [These days I do motivational speaking to corporations and the kids are often gray or bald or paunchy.] They come up and say it was nice to learn that ballplayers were human beings, but what they got from the book was moral support for a point of view. They claim that Ball Four gave them strength to be the underdog and made them feel less lonely as an outsider in their own lives. Or it helped them to stand up for themselves and see life with a sense of humor. Then they invariably share a funny story about a coach, a teacher, or a boss who reminds them of someone in the book.

In some fraternities and dorms they play Ball Four Trivia, or Who Said That? quoting characters from the book. And there is always someone who claims to hold the campus record for reading it 10, 12, or 14 times. Then they produce dog-eared copies for me to sign. I love it.

Sometimes when people compliment me about my book I wonder who theyre talking about. A librarian compared Ball Four to the classic The Catcher in the Rye because she said I was an idealist like Holden Caulfield who viewed the world through jaundice colored glasses. Teachers have personally thanked me for writing the only book their nonreading students would read. And one mother said she wanted to build me a shrine for writing the only book her son ever finished.

The strangest part is that apparently there is something about the book which makes people feel Im their friend. Im always amazed when I walk through an airport, for example, and someone Ive never met passes by and says simply, Hey, Ball Four. Or strangers will stop me on the street and ask how my kids are doing.

Maybe they identify with me because we share the same perspective. One of my roommates, Steve Hovley, said I was the first fan to make it to the major leagues. Ball Four has the kinds of stories an observant next-door neighbor might come home and tell if he ever spent some time with a major-league team. Whatever the reasons, it still overwhelms me to think that I wrote something which people remember.

I certainly didnt plan it this way. I dont believe I could have produced this response if I had set out to do it. In fact, twenty years ago when I submitted the final manuscript I was not optimistic. My editor, Lenny Shecter, and I had spent so many months rewriting and polishing that after awhile it all seemed like cardboard to us. Whats more, the World Publishing Company wasnt too excited either. They doubted there was any market for a diary by a marginal relief pitcher on an expansion team called the Seattle Pilots.

With a first printing of only 5,000 copies I was certain that Ball Four was headed the way of all sports books. And then a funny thing happened. Some advance excerpts appeared in Look magazine and the baseball establishment went crazy. The team owners became furious and wanted to ban the book. The Commissioner, Bowie Ayatollah Kuhn, called me in for a reprimand and announced that I had done the game a grave disservice. Sportswriters called me names like traitor and turncoat. My favorite was social leper. Dick Young of the Daily News thought that one up.

The ballplayers, most of whom hadnt read it, picked up the cue. The San Diego Padres burned the book and left the charred remains for me to find in the visitors clubhouse. While I was on the mound trying to pitch, players on the opposing teams hollered obscenities at me. I can still remember Pete Rose, on the top step of the dugout screaming, Fuck you, Shakespeare.

All that hollering and screaming sure sold books. Ball Four went up to [500,000 in hardcover, 5 million in paperback], and got translated into Japanese. Its the largest selling sports book ever. I was so grateful I dedicated my second book, Im Glad You Didnt Take It Personally, to my detractors. I dont think they appreciated the gesture.

One way I can tell is that I never get invited back to Old-Timers Days. Understand, everybody gets invited back for Old-Timers Day no matter what kind of rotten person he was when he was playing. Muggers, drug addicts, rapists, child molesters, all are forgiven for Old-Timers Day. Except a certain author.

The wildest thing is that they wouldnt forgive a cousin who made the mistake of being related to me. Jeff Bouton was a good college pitcher who dreamed of making the big leagues someday. But after Ball Four came out a Detroit Tiger scout told him hed never make it in the pros unless he changed his name! Jeff refused, and a month after he signed he was released. For the rest of his life, hell never know if it was his pitching or his name.

I believe the overreaction to Ball Four boiled down to this: People simply were not used to reading the truth about professional sports.

The owners, for their part, saw this as economically dangerous. What made them so angry about the book was not the locker room stories but the revelations about how difficult it was to make a living in baseball. The owners knew that public opinion was important in maintaining the controversial reserve clause which teams used to control players and hold down salaries. They lived in fear that this special exemption from the anti-trust laws, originally granted by Congress and reluctantly upheld in the courts, might someday be overturned.

To guard against this, the Commissioner and the owners (with help from sportswriters), had convinced the public, the Congress, and the courtsand many players!that the reserve clause was crucial in order to maintain competitive balance. (As if there was competitive balance when the Yankees were winning 29 pennants in 43 years.) The owners preached that the reserve clause was necessary to stay in business, and that ballplayers were well paid and fairly treated. (Mickey Mantles $100,000 salary was always announced with great fanfare while all the $9,000 and $12,000 salaries were kept secret.) The owners had always insisted that dealings between players and teams be kept strictly confidential. They knew that if the public ever learned the truth, it would make it more difficult to defend the reserve clause against future challenges.