India Briefing, 1989

India Briefing, 1989

edited by

Marshall M. Bouton and Philip Oldenburg

with the assistance of Sarah H. Beckjord

Published in cooperation with

The Asia Society

First published 1989 by Westview Press

Published 2018 by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1989 by The Asia Society

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress ISSN: 0894-5136

ISBN 13: 978-0-367-00331-9 (hbk)

Contents

LLOYD I. RUDOLPH

T. N. NINAN

PAUL R. BRASS

DARRYL D'MONTE

M. V. DESAI

MADHU KISHWAR AND RUTH VANITA

Guide

India's ninth general election will occur in late 1989, but already in 1988 election-oriented politics dominated the country's attention. Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, still on the defensive for his controversial handling of the Punjab crisis and the alleged involvement of key government officials in corruption, struggled to regain the political initiative. The success of Gandhi's efforts was limited, however, by setbacks such as the withdrawal of his defamation bill due to wide-spread criticism that it would curb press freedom. Meanwhile, opposition political parties and leaders struggled in vain to create an effective and unified electoral force. On the economic front, however, a solid recovery from the previous year's drought-induced slump bolstered the Congress (I) government and led to a sharp increase in private business activity.

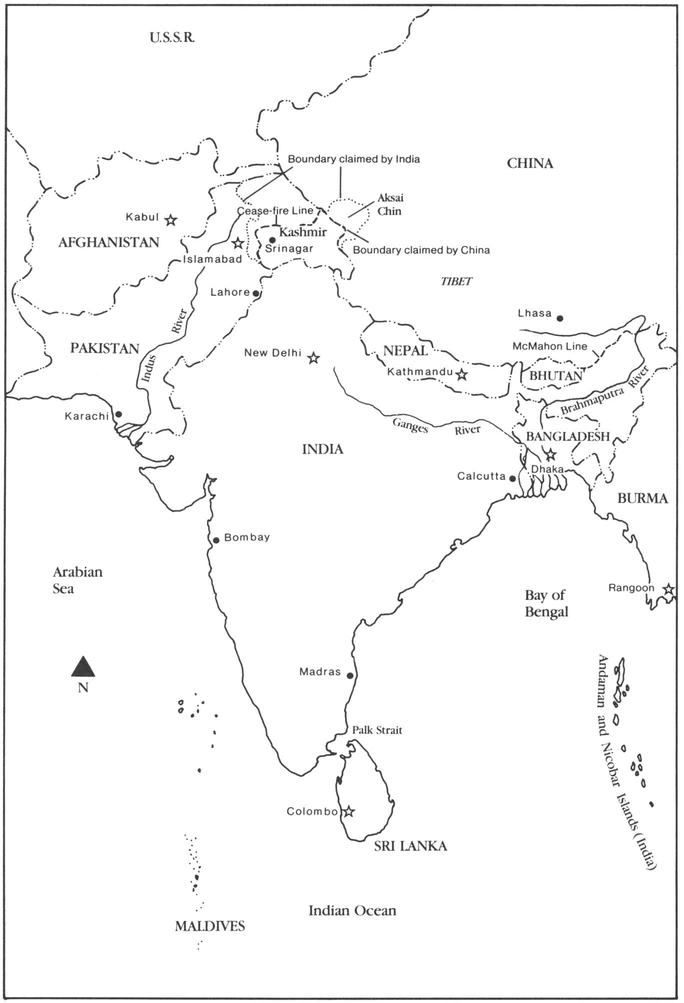

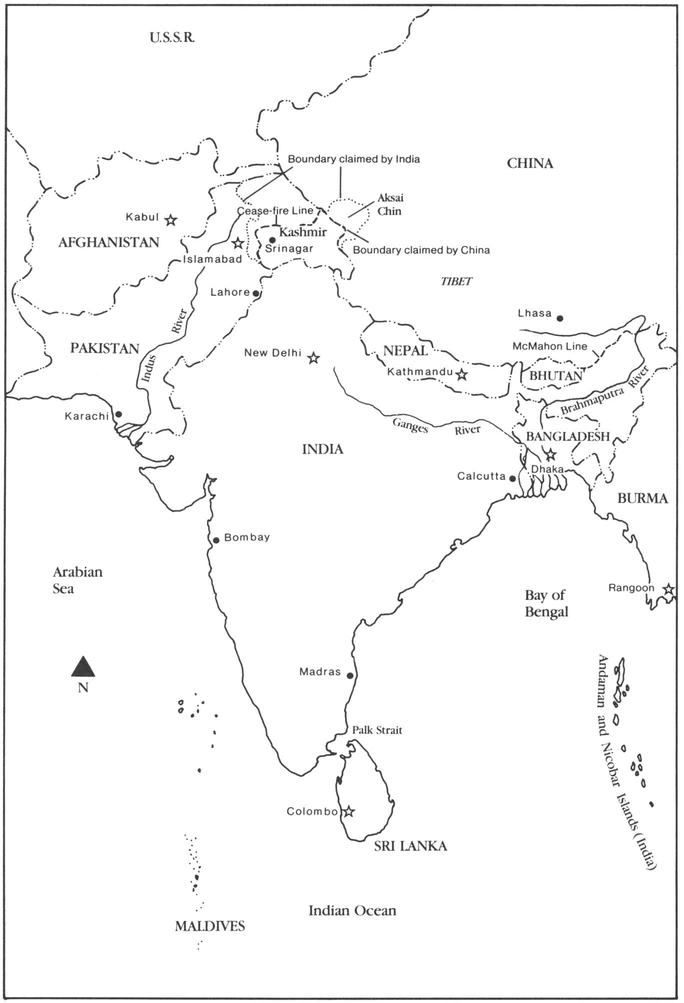

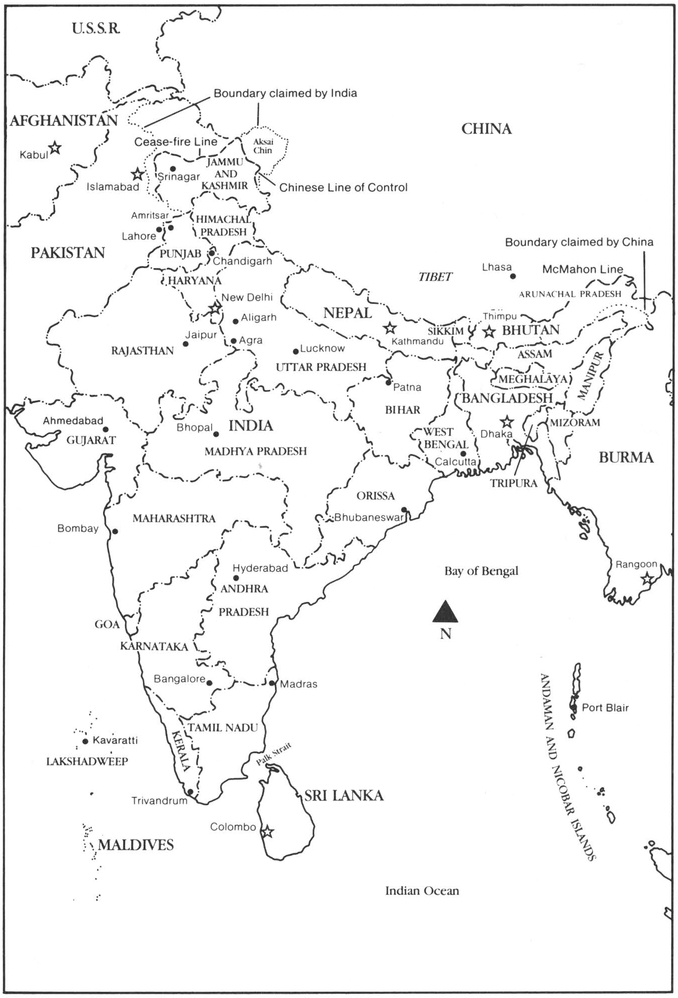

In foreign policy, India sought to come to terms with a rapidly changing regional and global environment, created by events such as the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan, the advent of a new, democratically elected government in Pakistan, and rapidly improving Sino-Soviet relations. As the year drew to a close, Rajiv Gandhi's visits to China and Pakistan were important steps with still uncertain conse-quences.

India Briefing, 1989 is the third in a series of annual assessments of key events and issues in Indian affairs prepared by the Contemporary Affairs Department of The Asia Society. As in earlier volumes, India Briefing, 1989 covers the year's developments in Indian politics, foreign policy, and the economy. This year's volume includes special chapters on elections, the press, women, and the environment. The volume is the companion to the annual China Briefing, also copublished by The Asia Society and Westview Press. The Asia Society is a nonprofit, nonpartisan educational organization dedicated to increasing U.S. understanding of Asia and its growing importance to the United States and to world relations.

The editors wish to express deep appreciation to all of the authors of India Briefing, 1989 for their hard work under rigorous deadlines. We are also grateful to Susan McEachern and her colleagues at Westview Press for their continued support of this effort.

Several individuals at The Asia Society were indispensable to the production of India Briefing, 1989. Sarah H. Beckjord managed the editing and production of the volume, and Andrea Sokerka provided invaluable assistance. Steve Tuemmler wrote the chronology and provided excellent research and editorial assistance, as did Hannah Bloch. Interns Jim Lande and Shaheen Mistri were crucial in the fact-checking process, and Chip Gagnon skillfully prepared the manuscripts for publication.

Marshall M. Bouton

The Asia Society

Philip Oldenburg

Columbia University

July 1989

1

The Faltering Novitiate: Rajiv at Home and Abroad in 1988

Lloyd I. Rudolph

Rajiv Gandhi, grandson of Jawaharlal Nehru, son of Indira Gandhi, and spokesman for what Salman Rushdie called midnight's children, the generation born after August 1947, seemed for a time to be revitalizing his grandfather's vision of a "modern" 21st century India. It was to be an India of high-tech industry, efficient management, and "clean" and constitutional government. This was the vision that ushered in Rajiv's debut as prime minister in late 1984. By the end of 1988, Gandhi was four years into his five-year term. His first year had been perceived as a time of mastery, the succeeding three as a time of drift. Toward the close of 1989, India was scheduled to hold its ninth parliamentary election. For the prime minister who had begun his term so auspiciously, the portents of a second term were unfavorable.

What can 1988 tell us about India's contested past, contingent present, and uncertain future? More than in most years, politics in 1988 was in the making. The credibility and skill with which Rajiv Gandhi and his political rivals, led by V. P. Singh, conducted themselves would largely determine the outcome of the 1989 election. How did Rajiv Gandhi understand and deal with domestic politics and foreign policy in the run up to the electorate's judgment of him after five years in power?

Rajiv Gandhi is the fourth generation of what in Indian political parlance is referred to as the Nehru dynasty. As the heir to the dynasty's political capital, he was uniquely positioned to claim and be granted the mantle of national leadership. His great-grandfather, Motilal Nehru, was one of a handful of top leaders of the Indian National Congress, the movement and party that in 1947 brought independence to India. His mother, Indira Gandhi, and grandfather, Jawaharlal Nehru, were for seventeen and fifteen years respectively prime ministers of India. Like his mother, Rajiv benefited from Mahatma Gandhi's choice of Jawaharlal as his political heir, making him the founder of the modern Indian state and leader of the Congress party, and connecting him to the newly enfranchised village electorate and the political class that constituted the vanguard of the nationalist movement. Rajiv's political capital included the villagers who regarded the Congress government as their grandfathers' generation had regarded the British raj, as sarkar (government). Like the monsoon, sarkar was a natural part of life, sometimes generous, sometimes cruel, but always present. If Rajiv Gandhi had a problem, it was that his mother, by her personalistic political style, had eroded the Nehru dynasty's political capital, sapping the institutional strength of the nationalist movement under Gandhi.

Rajiv entered politics some months after the death of his younger brother Sanjay, the first heir apparent, in a daredevil plane crash in New Delhi. His entry had been reluctant, over the objections of his Italian wife, Sonia, and with misgivings about giving up his career as a pilot for Indian Airlines. Between 1981 and the December 1984 election, he became chief courtier and principal point man for his mother's brand of highly personalized, no-holds-barred politics, helping, for example, to "topple" recalcitrant state chief ministers. In 1984, two months after the assassination of his mother by her Sikh secessionist bodyguards, he won the greatest election victory in Congress history. During the December 1984 campaign, the "old" Rajiv, portrayed as the grieving son of a martyred mother, accused his opponents of subversion and rallied Hindus against minority communities.