AUTHORS' NOTE

NA: The Secret of Life was conceived over dinner in 1999. Under discussion was how best to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the discovery the double helix. Publisher Neil Patterson joined one of us, James D. Watson, in dreaming up a multifaceted venture including this book, a television series, and additional more avowedly educational projects. Neil's presence was no accident: he published JDW's first book, The Molecular Biology of the Gene, in 1965, and ever since has lurked genielike behind JDW's writing projects. Doron Weber at the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation then secured seed money to ensure that the idea would turn into something more concrete. Andrew Berry was recruited in 2000 to hammer out a detailed outline for the TV series and has since become a regular commuter between his base in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and JDW's at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on the north coast of Long Island, close to New York City.

NA: The Secret of Life was conceived over dinner in 1999. Under discussion was how best to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the discovery the double helix. Publisher Neil Patterson joined one of us, James D. Watson, in dreaming up a multifaceted venture including this book, a television series, and additional more avowedly educational projects. Neil's presence was no accident: he published JDW's first book, The Molecular Biology of the Gene, in 1965, and ever since has lurked genielike behind JDW's writing projects. Doron Weber at the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation then secured seed money to ensure that the idea would turn into something more concrete. Andrew Berry was recruited in 2000 to hammer out a detailed outline for the TV series and has since become a regular commuter between his base in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and JDW's at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on the north coast of Long Island, close to New York City.

From the start, our goal was to go beyond merely recounting the events of the past fifty years. DNA has moved from being an esoteric molecule only of interest to a handful of specialists to being the heart of a technology that is transforming many aspects of the way we all live. With that transformation has come a host of difficult questions about its impactpractical, social, and ethical. Taking the fiftieth anniversary as an opportunity to pause and take stock of where we are, we give an unabashedly personal view both of the history and of the issues. Moreover, it is JDW's personal view and is accordingly written in the first-person singular. The double helix was already ten years old when DNA was working its in utero magic on a fetal AB.

We have tried to write for a general audience, intending that someone with zero biological knowledge should be able to understand the book's every word. Every technical term is explained when first introduced. Should you need to refresh your memory about a term when you come across one of its later appearances, you can refer to the index, where such words are printed in bold to make locating them easy; a number also in bold will take you to the page on which the term is defined. We have inevitably skimped on many of the technical details and recommend that readers interested in learning more go to DNAi.org, the Web site of the multimedia companion project, DNA Interactive, aimed at high-schoolers and entry-level college students. Here you will find animations explaining basic processes and an extensive archive of interviews with the scientists involved. In addition, the Further Reading section lists books relevant to each chapter. Where possible we have avoided the technical literature, but the titles listed nevertheless provide a more in-depth exploration of particular topics than we supply.

We thank the many people who contributed generously to this project in one way or another in the acknowledgments at the back of the book. Four individuals, however, deserve special mention. George Andreou, our preternaturally patient editor at Knopf, wrote much more of this bookthe good bitsthan either of us would ever let on. Kiryn Haslinger, our superbly efficient assistant at Cold Spring Harbor Lab, cajoled, bullied, edited, researched, nit-picked, mediated, wroteall in approximately equal measure. The book simply would not have happened without her. Jan Witkowski, also of Cold Spring Harbor Lab, did a marvelous job of pulling together chapters 10, 11, and 12 in record time and provided indispensable guidance throughout the project. Maureen Berejka, JDW's assistant, rendered sterling service as usual in her capacity as the sole inhabitant of Planet Earth capable of interpreting JDW's handwriting.

James D. Watson

Cold Spring Harbor, New York

Andrew Berry

Cambridge, Massachusetts

INTRODUCTION

THE SECRET OF LIFE

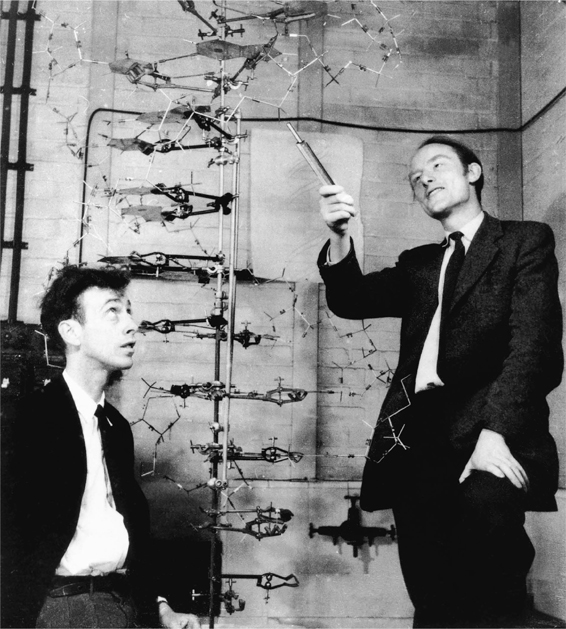

s was normal for a Saturday morning, I got to work at Cambridge University's Cavendish Laboratory earlier than Francis Crick on February 28, 1953. I had good reason for being up early. I knew that we were closethough I had no idea just how closeto figuring out the structure of a then little-known molecule called deoxyribonucleic acid: DNA. This was not any old molecule: DNA, as Crick and I appreciated, holds the very key to the nature of living things. It stores the hereditary information that is passed on from one generation to the next, and it orchestrates the incredibly complex world of the cell. Figuring out its 3-D structurethe molecule's architecture would, we hoped, provide a glimpse of what Crick referred to only half-jokingly as the secret of life.

s was normal for a Saturday morning, I got to work at Cambridge University's Cavendish Laboratory earlier than Francis Crick on February 28, 1953. I had good reason for being up early. I knew that we were closethough I had no idea just how closeto figuring out the structure of a then little-known molecule called deoxyribonucleic acid: DNA. This was not any old molecule: DNA, as Crick and I appreciated, holds the very key to the nature of living things. It stores the hereditary information that is passed on from one generation to the next, and it orchestrates the incredibly complex world of the cell. Figuring out its 3-D structurethe molecule's architecture would, we hoped, provide a glimpse of what Crick referred to only half-jokingly as the secret of life.

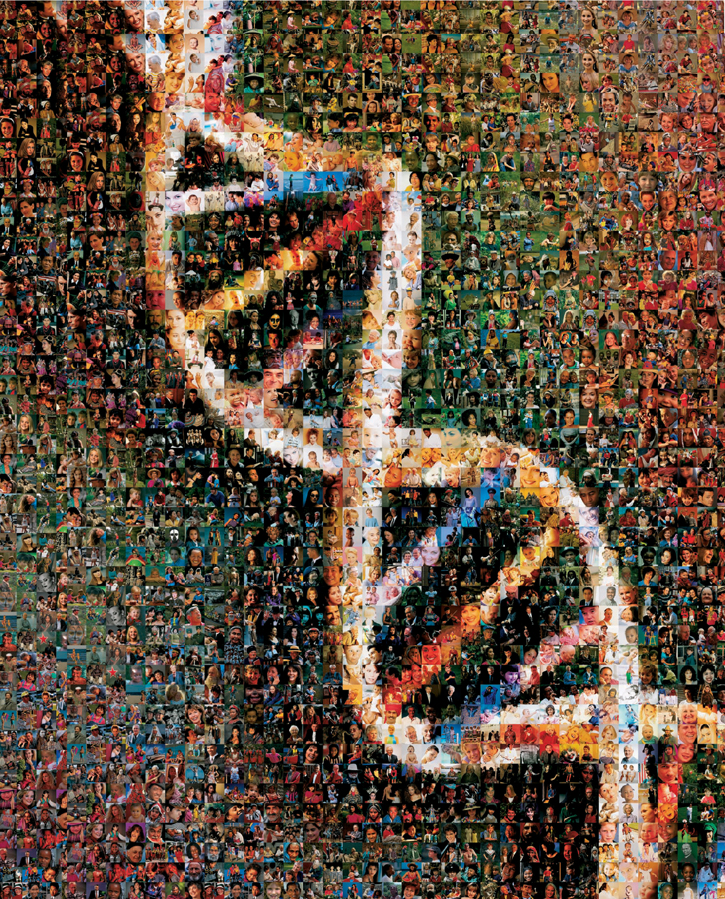

We already knew that DNA molecules consist of multiple copies of a single basic unit, the nucleotide, which comes in four forms: adenine (A), thymine (T), guanine (G), and cytosine (C). I had spent the previous afternoon making cardboard cutouts of these various components, and now, undisturbed on a quiet Saturday morning, I could shuffle around the pieces of the 3-D jigsaw puzzle. How did they all fit together? Soon I realized that a simple pairing scheme worked exquisitely well: A fitted neatly with T, and G with C. Was this it? Did the molecule consist of two chains linked together by A-T and G-C pairs? It was so simple, so elegant, that it almost had to be right. But I had made mistakes in the past, and before I could get too excited, my pairing scheme would have to survive the scrutiny of Crick's critical eye. It was an anxious wait. But I need not have worried: Crick realized straightaway that my pairing idea implied a double-helix structure with the two molecular chains running in opposite directions. Everything known about DNA and its propertiesthe facts we had been wrestling with as we tried to solve the problemmade sense in light of those gentle complementary twists. Most important, the way the molecule was organized immediately suggested solutions to two of biology's oldest mysteries: how hereditary information is stored, and how it is replicated. Despite this, Crick's brag in the Eagle, the pub where we habitually ate lunch, that we had indeed discovered that secret of life, struck me as somewhat immodest, especially in England, where understatement is a way of life.

NA: The Secret of Life was conceived over dinner in 1999. Under discussion was how best to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the discovery the double helix. Publisher Neil Patterson joined one of us, James D. Watson, in dreaming up a multifaceted venture including this book, a television series, and additional more avowedly educational projects. Neil's presence was no accident: he published JDW's first book, The Molecular Biology of the Gene, in 1965, and ever since has lurked genielike behind JDW's writing projects. Doron Weber at the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation then secured seed money to ensure that the idea would turn into something more concrete. Andrew Berry was recruited in 2000 to hammer out a detailed outline for the TV series and has since become a regular commuter between his base in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and JDW's at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on the north coast of Long Island, close to New York City.

NA: The Secret of Life was conceived over dinner in 1999. Under discussion was how best to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the discovery the double helix. Publisher Neil Patterson joined one of us, James D. Watson, in dreaming up a multifaceted venture including this book, a television series, and additional more avowedly educational projects. Neil's presence was no accident: he published JDW's first book, The Molecular Biology of the Gene, in 1965, and ever since has lurked genielike behind JDW's writing projects. Doron Weber at the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation then secured seed money to ensure that the idea would turn into something more concrete. Andrew Berry was recruited in 2000 to hammer out a detailed outline for the TV series and has since become a regular commuter between his base in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and JDW's at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory on the north coast of Long Island, close to New York City. s was normal for a Saturday morning, I got to work at Cambridge University's Cavendish Laboratory earlier than Francis Crick on February 28, 1953. I had good reason for being up early. I knew that we were closethough I had no idea just how closeto figuring out the structure of a then little-known molecule called deoxyribonucleic acid: DNA. This was not any old molecule: DNA, as Crick and I appreciated, holds the very key to the nature of living things. It stores the hereditary information that is passed on from one generation to the next, and it orchestrates the incredibly complex world of the cell. Figuring out its 3-D structurethe molecule's architecture would, we hoped, provide a glimpse of what Crick referred to only half-jokingly as the secret of life.

s was normal for a Saturday morning, I got to work at Cambridge University's Cavendish Laboratory earlier than Francis Crick on February 28, 1953. I had good reason for being up early. I knew that we were closethough I had no idea just how closeto figuring out the structure of a then little-known molecule called deoxyribonucleic acid: DNA. This was not any old molecule: DNA, as Crick and I appreciated, holds the very key to the nature of living things. It stores the hereditary information that is passed on from one generation to the next, and it orchestrates the incredibly complex world of the cell. Figuring out its 3-D structurethe molecule's architecture would, we hoped, provide a glimpse of what Crick referred to only half-jokingly as the secret of life.