Contemporary Approaches to Film and Television Series

A complete listing of the books in this series can be found online at wsupress.wayne.edu

General Editor

Barry Keith Grant

Brock University

Advisory Editors

Patricia B. Erens

School of the Art Institute of Chicago

Lucy Fischer

University of Pittsburgh

Caren J. Deming

University of Arizona

Robert J. Burgoyne

Wayne State University

Tom Gunning

University of Chicago

Anna McCarthy

New York University

Peter X. Feng

University of Delaware

Lisa Parks

University of CaliforniaSanta Barbara

Jeffrey Sconce

Northwestern University

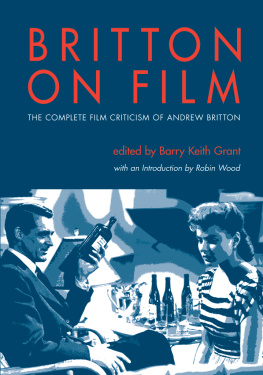

BRITTON ON FILM

THE COMPLETE FILM CRITICISM OF ANDREW BRITTON

edited by Barry Keith Grant

with an Introduction by Robin Wood

WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS

DETROIT

2009 by Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan 48201.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without formal permission. Manufactured in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Britton, Andrew, 19521994.

Britton on film : the complete film criticism of Andrew Britton / edited by Barry Keith Grant ; with an introduction by Robin Wood.

p. cm. (Contemporary approaches to film and television series)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8143-3363-1 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Motion pictures. I. Grant, Barry Keith, 1947 II. Title.

PN1994.B68 2008

791.43dc22

2008019046

ISBN 978-0-8143-3550-5 (e-book)

To Art Efron, a mentor who taught me so much about criticism, and Robin Wood, who first showed me how to be a critic of cinema

Andrew Britton was born in Salisbury, Wiltshire, in the United Kingdom in April 1952. He graduated in 1974 with a first-class degree in English and American Literature from Kings College, London, and went on to study as a postgraduate at the University of Warwick with noted film critic Robin Wood.

Brittons career as a lecturer in Film Studies began at the same university in 1978, and he went on to teach at Essex University (197985), Trent University, Ontario, Canada (198588), York University, Ontario, Canada (198889), and Reading University, England (199293). He was also a guest lecturer at other universities in Britain, Canada, and the United States, including a term as a visiting professor at Queens University, Ontario, Canada in 1983.

Britton was a member of the editorial boards of the film magazines Framework and Movie and of the editorial collective of the Canadian magazine CineAction. In 198990, he was involved in program research at the National Film Theatre in London, and in 1991, he was editor of the official program of the London Film Festival. Britton was also a joint contributor to The American Nightmare: Essays on the Horror Film (1979) and the editor of Talking Films (1991). His book Katharine Hepburn: The Thirties and After (released in the United States as Katharine Hepburn: Star as Feminist) was nominated for the British Film Institutes Book of the Year Award in 1985.

Britton died of complications from AIDS in April 1994.

Contents

Preface

I met Andrew Britton only once, and that was just briefly. It must have been in late 1986 or early 1987, when I was visiting Robin Wood and Richard Lippe in their Toronto apartment to deliver (this was before the days of e-mail and the Internet) a final copy of my essay on Tobe Hoopers remake of Invaders from Mars for publication in their film journal, CineAction. Although at that time the journal still had the exclamation mark attached to its name, certainly the moment had nothing of the drama that Wood describes in his introduction to this volume of his first meeting with Britton, whom he was taking on as a graduate student. In my case, I had been chatting amiably with Robin and the other members of the magazines editorial collective when there was a knock at the door. It was Andrew, I believe just arriving or returning from the UK, for there was an intense and joyful connection that immediately arose between him and Robin when Andrew entered the room that implied a lengthy separation. I have a mental image of Andrews face, politely saying hello to me when introduced but already looking beyond and then moving past me, his attention fixed on Robin. The connection between them was so strong, so palpable, that it seemed to exclude all else, certainly a stranger like myself. There was nothing for me but to depart, and as quickly as possible, I humbly took my leave.

Although Britton had hardly taken notice of me, I certainly had been aware of him for years through his writing. The horror film and the American Gothic had long been an interest of mine, and I remember the pleasure I took upon first reading The Devil, Probably, his contribution to The American Nightmare, the landmark book on the horror film based around the retrospective that Wood programmed in 1979 for the Toronto International Film Festival (then known as the Festival of Festivals). Periodically, I would come across an essay by Britton, primarily through CineAction or Movie, and marvel at its erudition as well as the surgical precision with which he could critique a theoretical argument. Yes, he was merciless in his dissections, but he also wasthere is no other word for itfunny. He possessed an inimitable ability to demolish a critical position while at the same time demonstrating a remarkably rich sense of humor. Coming to film studies with a background in literature, as I hadand suspected that Britton did as wellI particularly admired his ability to move with intellectual ease and assurance between cinema and prose fiction.

In the essay on Invaders from Mars that I discreetly deposited on the table on my way out after meeting Britton, I compared the film to the 1953 original, directed by William Cameron Menzies, in order to tease out the implications of what I called Science Fiction in the Age of Reagan. At the same time, Britton was publishing his much more ambitious and important piece Blissing Out: The Politics of Reaganite Entertainment. His essay was astonishingly comprehensive in scope, monumental even, mine much more modest, but it was only one of a number of occasions when I took delight in discovering that this distinctive and always interesting critic was on a wavelength similar to mine.

Skeptical of theoretical trends, Britton was a critic who was remarkably attuned to the nuances of texts, whether cinema or literature. Consider his thorough readings of Meet Me in St. Louis and Now, Voyager as examples of his ability to provide fresh and compelling interpretations of canonical Hollywood films which have been the focus of much critical attention; by contrast, the essay on Mandingo shows how Britton managed to discover considerable value in a movie that otherwise had been completely overlooked by film scholars. Britton was able to question and resist the ideas of others because he was so persuasively detailed in his own analyses. Admirably, he did not shrink from exposing flaws even in important works by major artists, as he convincingly does, for example, in his discussion of Jean-Luc Godards Tout va bien. Brittons grasp of theory, particularly Marxism and psychoanalysis, was extraordinary. His critiques of Screens theoretical views and Wisconsin formalism are the most convincing I know. Yet, although he was adept with theory, he was less a theorist than a critic. By this I do not mean to suggest that theory and criticism are mutually exclusive, and Brittons work demonstrates as well as anyones how they might work together.

Next page