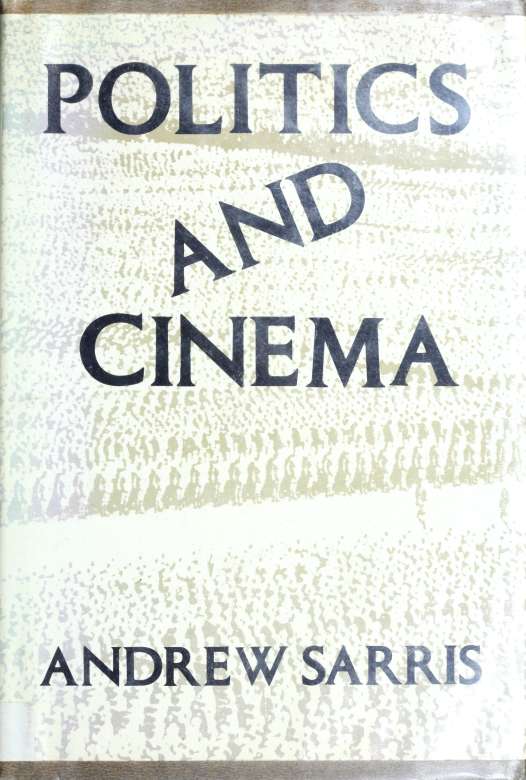

Politics and Cinema

Dreiser and James: with that juxtaposition we are immediately at the dark and bloody crossroads where literature and politics meet.

Lionel Trilling, Reality in America

The sin of nearly all left-wingers from 1933 onwards is that they have wanted to be anti-Fascist without being anti-totalitarian.

George Orwell, 1944

Introduction

AS I LOOK BACK on my critical ruminations I am surprised tc discover that the political animal in me persisted long after I started walking on the yellow brick road beyond the silver screen. My iate father had brought me up to believe that politics and business were manly activities whereas the arts were strictly for sissies and empty-headed womanizers. My earliest fantasies and "ideas" were therefore political rather than artistic. I wish neither to exaggerate my father's influence nor to suggest that it was at all unusual in American experience. Although my father was a Greek immigrant his notions of what was serious and what was frivolous fitted in very snugly with the Puritan tradition. His attitude toward movies was appropriately utilitarian. The theme, the moral, the message, if you will, were all-important. The style? If my father ever thought or that slithery word it would have been in connection with women's fashions. That I would one day become a certified scholar of cinematic style never entered his mind or mine back in the supposedly formative years when one imagines that one's destiny can be freely and logically determined. Growing up as I did in the heady atmosphere of political debate at the kitchen table I had no way of anticipating the long, discouraging years in which I scrounged for a living as a scribbler. Thus when I gladly settled for becoming a chronicler of shadows I was still haunted by memories of more substantial concerns.

I generally date myself as a movie reviewer by noting that my first pieces were published in 1955, the year in which the essayistic voices of James Agee and Robert Warshow were stilled forever. By citing this odd coincidence I do not mean to imply that my criticism rushed in to fill a cultural vacuum caused by the loss of two legendary figures in the field. Film criticism was not taken all that seriously in the mid-fifties, and even Agee and Warshow were insufficiently appreciated until their collected writings were published posthumously. Since then their influence has been enormous, of course, and in many ways they have proved to be irreplaceable. I certainly do not claim to be

INTRODUCTION 2

their direct descendant either stylistically or ideologically. This kind of kinship must be conferred upon a critic by critics of critics. What I did inherit from Agee and Warshowand from many of their predecessors and contemporaries as wellwas a skeptical attitude toward the claims of politics on the cinema.

For the past half century these political claims have been mostly liberal, leftist, anarchistic, and even methodically Marxist. Rightists, by and large, have preferred to express their opposition to the alleged redness of movies with the blue pencil of censorship. Religious people have tended to mistrust the medium itself as the work of the devil rather than turn it to their own uses. This is not to say that a classically reactionary cinema has not always existed, particularly in Hollywood. But the terms in which even this cinema was discussed presupposed a generally leftward orientation in both the writer and the reader. Hence, the critical debate has raged not so much between left and right as between politics and aesthetics. After all, even workaday reviewers have to take a stand eventually against bad movies with good intentions. Otherwise they will find themselves marked for moral blackmail. What? You don't want to reelect Roosevelt? You don't want to stop Hitler? You don't want to prevent World War III? You don't want to end the Vietnam War? You don't want to help the poor? You don't want to end racial discrimination? To this litany of leading questions the allegedly apolitical critic can invoke the sacred abstraction of Art above all other considerations. And if D. W. Griffith be deemed a racist and a bigot, so was Shakespeare. As for social significance it is quite clear that Uncle Tom's Cabin changed more hearts and minds than Moby Dick, but Harriet Beecher Stowe does not therefore rise above Herman Melville in our literary estimations. Jean Renoir once remarked ruefully that he had made La Grande Illusion in 1936 as his statement against war, and in 1939 Europe went to war.

Actually, one seldom encounters in the seventies the resounding rhetoric of social consciousness and socialist realism so common in the thirties and the forties. Absurdism, alienation, anomie have become so much the order of the day in high art that the Old Left's evangelical exhortations to the common man and the little people now seem naive and sentimental. The very subtle anti-Stalinism of Agee and Warshow in the forties and the fifties is difficult to appreciate in the rather easily cynical seventies atmosphere in which all

INTRODUCTION

forms of authority are suspect. The God that Failed some time between the slaying of Trotsky and the subjugation of Czechoslovakia has never been resurrected as a monolithic object of faith. The encrusted solidarity of the Old Left has been replaced by the jagged fragmentation of the New Left. There is less talk of One World and more talk of the Third World. One hardly ever hears The Internationale even being hummed anymore as a common anthem of the Left. One hears instead a never ending concert of individualistic folk songs. Hence, the subordination of personal expression to social communication is no longer the article of faith it once was. The artist has been joined in the ivory tower by the terrorist. The once supposedly subversive workers have been transformed by their middle-class values into a counterrevolutionary force called labor. The Okies who fled to California in The Grapes of Wrath have become the staunch-est supporters of Ronald Reagan.

I am constantly reminded by my academic experiences of the widening generation gap between the world in which I grew up and the world in which I am growing old When I first started teaching film history in the mid-sixties the mention of the name McCarthy to my students meant only Gene, and not joe. By the mid-seventies my students had forgotten Gene as well. Hence, i have had to assign readings in Eisenstein and Pudovkin and Rotha and Kracauer and Spottiswoode and Reisz and Lindgren and Balasz and Manveil and Sadoul and Grierson and Wright and Arnheim so that all these forgotten Marxist film historians and aestheticians could provide a frame of reference for my own revisionist theories on the cinema. But is that enough? Or does all history, and not just film history, have to come back to life for old ideas to make sense? I would like to be able to slide back into the past with a casualness born of confidence in my readers. Too often, however, I am accused of pedantry and obscurantism for my efforts.