Table of Contents

Strangers in the rain.

for Greil Marcus

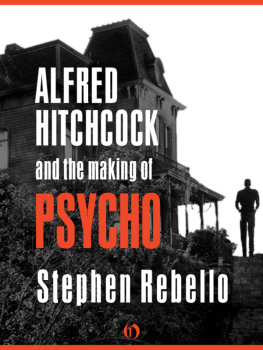

1960

THE MOVIES had always encouraged the idea that we were safe, secure, and warm in their dark. It is a comfortable and comforting place to be, for a nickel... or $12.50. Come in out of the heat, or the cold. Come in and forget your sorrows and the worlds hard times. Our theater has its own air-raid shelter. Take a break at the end of a long days drive. The cinema is a welcoming motel with fresh linen and a hot shower.

But how far did people trust that promise? The invitation was barbed: yes, we could see women undressing and men shooting guns as if the ammunition was forever. But only because we were not quite there, not in the screens there. We were voyeurs, never harmed by the bullets, but never able to handle the women. Yet there is a frisson of danger, toowe feel we cant escape from those dense rows of seated people. What if the building burns from the light of the arc projector? (And films did catch fire in the early days.) What if the controlled or censored circumstances of life on-screen suddenly give way to orgy and slaughter? (How dreadful! How delicious!) What if the locomotive comes out of the screen and strikes us? What if the knife we see before our eyes glows and grows until it fits and fills our hand and we are striking, striking?...

RIGHT FROM THE START, Psycho played with these and darker prospects. The feeling existed that this might be the most excruciatingly skillful film ever madeif you thought of film as a ghost train or a dream, or as an experiment with suspense. Anyone with any sense of film knew not just that Psycho changed cinema but that now the subversive secret was outtruly this medium was prepared for an outrage in which sex and violence were no longer games but were in fact everything. Psycho was so blatant that audiences had to laugh at it, to avoid the giddy swoon of evil and ordeal. The title warned that the central character was a bit of a nut, but the deeper lesson was that the audience in its self-inflicted experiment with danger might be crazy, too. Sex and violence were ready to break out, and censorship crumpled like an old ladys parasol. The orgy had arrived.

AT THE END OF THE 1950S, Hollywood seemed to be doing its thing in the same old way. It made The Searchers, Rio Bravo, and Man of the West, three of the best Westerns ever done. It produced Ben-Hur, Gigi, Giant, and Around the World in 80 Dayslarge entertainments boundless in budget and scope, but so tame to the imagination. It delivered musicals (The King and I, High Society, South Pacific), Biblical epics (The Ten Commandments), and inspiring stories of humanity and sacrifice (The Diary of Anne Frank, The Defiant Ones). And all these films ended well. Most had happy endings; even where Anne Frank died we were assured that her enemies were eventually defeated and that Annes virtue was an endless flame. Off to one side, there were a few unaccountable personal visions, movies about some inner America, full of dread and disorderKiss Me Deadly, Bigger Than Life, The Night of the Hunter, Sweet Smell of Success, Some Like It Hotglimpses of a real but alarming society (most of them still in black-and-white because it was harsh). But these were not the films Hollywood regarded as important.

The people who had founded the business were dying off. Those left told themselves movies were better than ever, and they said they were still in charge. But they were old men who did not realize how fast public taste was changing. There were already shrewd observers who saw that the big thingthe golden age, the unquestioning marriage of Hollywood and Americawas over. Sometimes it seemed that the ugly aftermath of goldenness, The Tarnished Angels (and that was a current title, too), was what the new fragmented films were revealing.

In 1958 American box office dropped below $1 billion a year, a figure it had held since the early 1940s. In the same year, the average weekly attendance at the movies fell to 35 million; it had been 82 million in 1946. Another statistic helped explain that decline. In the 50s, the number of American households with television went up from about 4 million to about 48 million. There wasnt any question about Americas, or the worlds, delight in moving picture stories. But staying at home with them felt easier, cheaper, and more natural. No matter how big or spectacular Hollywood made the movies, the audience took the smaller version. One of the most brilliant people in the city saw that light, and in the mid-1950s he augmented his theatrical pictures with a new TV series. It changed him more than he could have guessed.

When Alfred Hitchcock turned sixty on August 13, 1959, he was already the best-known film director in the United States. People liked his films: in the fifties Strangers on a Train, Dial M for Murder, Rear Window, To Catch a Thief, The Man Who Knew Too Much, and North by Northwest had all been popular hits, suspense stories served with the black cream of Hitchcocks humor. There had been other filmsI Confess, The Wrong Man, The Trouble with Harry, and Vertigothat had not been as successful. Still, Hitchcocks output in the fifties had been extraordinary, and in France, for example, he was widely regarded as a great artist. Two critics on their way to becoming filmmakers, Claude Chabrol and Eric Rohmer, had written a book about Hitchcock in 1957. A book about a filmmaker! It was a great novelty. In the fifties film was still so central as an entertainment that no one thought to write books about it.

Hitchcock had earned an uncommon reputation not just for suspense and mystery but for artful, teasing games played with moral responsibility. There were ways in which he asserted or advertised himself. He had a habit of putting himself in his own filmsfor a shot or a cameo momentand the habit had become famous if only because the round, respectable, and sedate-looking Hitchcock was at odds with the frantic action in his films. (You could hardly imagine Hitch in North by Northwest racing Cary Grant into the cornfield as the crop-dusting aircraft turned ugly. Nor could you picture Hitch himself drawing all those gorgeous women into embraces that seemed to go a few inches furtherand inches countthan censorship wished for.)

But it was in the 50s that this public recognition of Hitchcock was deepened by his new TV show, Alfred Hitchcock Presents. The show started playing in the fall of 1955 and would run for ten years. It was a showcase for mystery stories, often very well written and directed. Hitchcock even directed a few of the shows himself. But he graced every edition with a short on-camera introduction and farewell. These highlight spots stressed his fastidious, plummy way of speaking and his rather chilly, formal humor. They offered an intriguing contrast between nasty material and classy presentation, and they established Hitch (coming and going to lugubrious music, Gounods Funeral March of a Marionette) as a droll fellow who liked to make audiences sweat. The marketing of