Copyright 2005 by Jordan Fisher Smith

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

www.hmhco.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Fisher Smith, Jordan.

Nature noir : a park rangers patrol in the Sierra / Jordan Fisher Smith.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-618-22416-5

1. Fisher Smith, Jordan. 2. Park rangersUnited StatesAnecdotes. 3. United States. National Park ServiceOfficials and employees Anecdotes. 4. Natural historySierra Nevada (Calif. and Nev.) Anecdotes. I. Title.

SB 481.6. F 57 A 3 2005 363.28 dc22 2004059416

e ISBN 978-0-547-52649-2

v2.0516

This is a work of nonfiction based on the experiences of the author. However, some names, places, physical descriptions, and other particulars have been changed. For that reason, readers are cautioned that some details in the text may not correspond to real people, places, or events.

Chapter 7 of Nature Noir was previously published in a different form in the Autumn 1997 issue of Orion: People and Nature, and in the anthology Shadow Cat: Encountering the AmericanMountain, Susan Ewing and Elizabeth Grossman, eds., Sasquatch Books, Seattle, 1999. A passage from the Prologue was previously published in a different form in the April 1996 issue of the Wild Duck Review. Lyrics from Dont Worry, Be Happy, written and performed by Bobby McFerrin, ProbNoblem Music, are used with the gracious permission of ProbNoblem Music. Passages from Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching by Ursula K. Le Guin, 1997 reprinted by arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boston, www.shambhala.com.

To Ray Strieker, Joe Burrascano, and Dan Abramson, who rescued a rescuer

Prologue

A T THE AGE OF TWENTY-TWO , I decided to become a park ranger. I pursued that life with a freshness and single-mindedness I can scarcely bring to anything now. At twenty-eight, I could move around the mountains in summer or winter through any kind of weather. I could climb rock and ice, pack loads around the back-country with mules, fix trails, build with logs, read maps and aerial photographs, and find my position in any kind of country. I was impervious to the sight of blood. I could splint broken bones and I could locate a large vein in an arm or leg by feel and get an intravenous needle into it to save a life. You could drop me into a small fire with another ranger and I could build line around it. You could drop me into a big fire with a crew and I could stay alive and sleep when the nights got long in the warm ashes in the heart of it. I could shoot a pistol and hit the target every time. I could go out on skis in the winter and live in snow caves. And I was, I thought, an accomplished lover of the land.

In my first summer with the Forest Service, I lived in an old fish hatchery near the southwest corner of Yellowstone National Park. From there I hiked up the Warm River in the orange light of evening through clouds of mosquitoes in the willow thickets around the beaver dams, startling sandhill cranes, which would burst from the brush with strange cries and circle over me in fear for their hidden nests. Later I lived in a tent in Granite Basin and then in Alaska Basin in the Grand Tetons, and I kept my pots and little stove in a hollow tree when I was away from camp. I lived at the end of the road in an alpine valley in Sequoia National Park, and in the autumn I returned to my cabin on horseback at night in the sleet with my feet so cold I couldnt feel them, to stand in front of the stone fireplace and drink hot tea. In the winters I would go back to a job on the coast of Northern California, where I went to sleep to the sound of the waves on the beach and the foghorns and bells on the buoys beyond the harbor. Still later I spent a summer living in a tiny cabin in western Alaska, a long airplane flight from the nearest road.

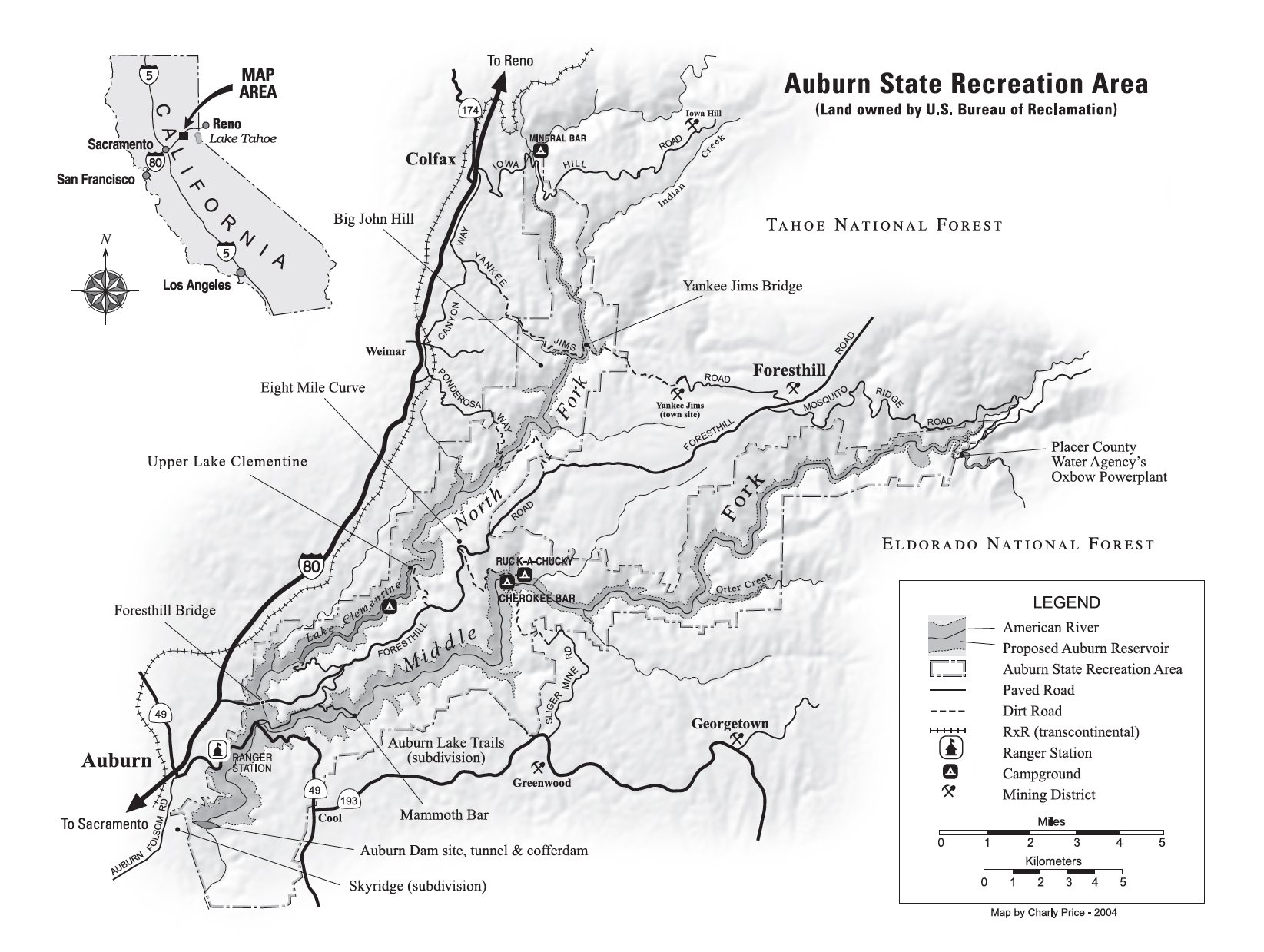

After all of that, I came to spend the greater part of my career watching over 48 miles of river and 42,000 acres of low-elevation California canyons that had suffered various forms of abuse for over a century and a half and had been condemned for a couple of decades to be inundated by a huge federal dam. And there probably wasnt a day when I didnt wonder how I came to choose this hopeless place on which to lavish my attention.

The path that led to the American River began like this: As a twenty-one-year-old student, Id been spending every spare moment I could in the mountains and Id resolved to find a way to make a living outdoors, as either a mountain guide or a ranger. As is often the case when youre young, in the end the choice between the two hinged upon happenstance. That September I sent out rsums for junior guide jobsone I remember involved packing loads of supplies for the senior guides and their clients up the glaciers of Mount Rainierbut the season was over and no one was hiring, so late that month a friend and I decided to go climbing in Yosemite.

Leaving our car at Tioga Pass, we began hiking toward an ice climb in the cirque of Mount Dana, laden with rope, ice axes, and clanking equipment. As we made our way higher the forests grew sparse. Between patches of meadow and bare rock, the few remaining pines had been shaped by a hundred or two hard winters, the exposed grain of old lightning and avalanche wounds on their trunks weathered amber in the sun, their undulant canopies following the curves of the glacier-polished granite outcrops against which theyd huddled for protection from the wind. With a variety of tiny and efficient cook stoves available to backpackers and climbers, the Park Service prohibited campfires in these high forests so no one would use these works of art as fuel. But we came upon a campsite, and in it two men were chopping the heart out of one of these trees for an already overfed campfire. Greeting them with as much friendliness as we could, my friend and I tried to explain how long that tree had taken to grow. The two men sneered, told us to mind our own business, and went back to what they were doing. And as I watched them finish vandalizing that beautiful tree, I remember I wanted, more than anything, a ranger uniform and a citation book.

Less than three years later I had both, and I thought I knew what I was doing. I was a summer wilderness ranger for the Forest Service in what is now the Jedediah Smith Wilderness in Idaho and Wyoming. Unarmed and entirely untrained for police work, one day I happened to walk into a campsite full of people who didnt think much of my uniform or the government I represented. When the yelling and shoving were over I was physically intact, but the idea that people could always be dissuaded from breaking the law by a lecture or a small piece of pink paper with no immediate consequences was slowly dying in me. The following autumn, one of the rangers I worked witha young woman who must have weighed all of 110 poundswas threatened with an ax by drunken hunters in the Palisades Range. Still, I hadnt gotten into rangering to be a policeman, and it was another two and a half years before I summoned the gumption to enroll in my first law enforcement academy. When I got out, I took a job patrolling the high country of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. I felt strange and self-conscious at first wearing the gun and handcuffs, but I told myself they were mainly symbolic and I had no intention of using them on anyone.

Next page