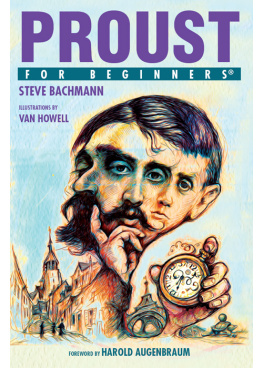

French Literature

A Beginners Guide

ONEWORLD BEGINNERS GUIDES combine an original, inventive, and engaging approach with expert analysis on subjects ranging from art and history to religion and politics, and everything in between. Innovative and affordable, books in the series are perfect for anyone curious about the way the world works and the big ideas of our time.

aesthetics

africa

american politics

anarchism

anticapitalism

aquinas

art

artificial intelligence

the bahai faith

the beat generation

biodiversity

bioterror & biowarfare

the brain

british politics

the buddha

cancer

censorship

christianity

civil liberties

classical music

climate change

cloning

cold war

conservation

crimes against humanity

criminal psychology

critical thinking

daoism

democracy

dewey

descartes

dyslexia

energy

engineering

the enlightenment

epistemology

the european union

evolution

evolutionary psychology

existentialism

fair trade

feminism

forensic science

french revolution

genetics

global terrorism

hinduism

history of science

humanism

islamic philosophy

journalism

judaism

lacan

life in the universe

literary theory

machiavelli

mafia & organized crime

magic

marx

medieval philosophy

middle east

modern slavery

NATO

nietzsche

the northern ireland conflict

oil

opera

the palestineisraeli conflict

particle physics

paul

philosophy of mind

philosophy of religion

philosophy of science

planet earth

postmodernism

psychology

quantum physics

the quran

racism

religion

renaissance art

shakespeare

the small arms trade

sufism

the torah

the united nations

volcanoes

A Oneworld Paperback Original

Published by Oneworld Publications 2012

Copyright Carol Clark 2011

The moral right of Carol Clark to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved

Copyright under Berne Convention

A CIP record for this title is available

from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-85168-899-9 (pbk)

ISBN 978-1-78074-092-8 (ebk)

Typeset by Cenveo Publisher Services, Bangalore, India

Cover design by vaguelymemorable.com

Printed and bound in Great Britain by xxx

Oneworld Publications

185 Banbury Road

Oxford OX2 7AR

UK

Learn more about Oneworld. Join our mailing list to find out about our latest titles and special offers at: www.oneworld-publications.com

List of illustrations

Acknowledgements

I should like to thank my former colleagues at the University of Glasgow, Balliol College, Oxford, and the University of Oxford, first for appointing me to my Fellowship and Lectureships and then for their patience with me over many years. Their decisions allowed me to spend the best part of my working life reading great French books and discussing them with intelligent young people: a wonderful way to earn ones living.

I am also grateful to my students for their ideas and stimulation, and to the librarians at the University of Glasgow Library, the Taylor Institution Library, Oxford, the Bibliothque Nationale (now Bibliothque de France), Paris, and the Bibliothque Historique de la Ville de Paris, for all their help.

I wish also to thank the Bibliothque de France for permission to reproduce Figures 1 and 2, and ditions Gallimard for the extract from Jean-Paul Sartres Le Mur (Text 18).

Carol Clark

Oxford and Paris

Introduction

Why would one want to read French literature?

The literature of the French language is the longest-lived and richest of all European literatures apart from English. Until very recent years, it was a model for writers worldwide. Medieval French writers gave us the stories of Arthur, the Round Table and the Holy Grail, and, some would say, the ideal of romantic love. Montaignes Essays have been read continuously by English speakers since they were first translated in 1603, and are still finding enthusiastic readers today. Molires character comedy has been an inspiration for writers in England and everywhere in Europe. The realistic novel of the French nineteenth century became the model for novelists worldwide, including America and Japan, and for the structure of the feature film. The cinema itself was a French invention, and is regarded by many French people as the chief art form of the twentieth century (le septime art). Every century has produced its crop of poetry and prose, history, fiction, comedy and tragedy, with new forms constantly appearing as audiences changed and grew.

The readership for literature in French has never been restricted to metropolitan France. A whole French-speaking literature developed in England in the two centuries following the Norman Conquest, while in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries French became the language of cultivated Europe as far as Russia. The determined imposition of French language and literary study in the education systems of its former colonies produced writers who could express the feelings and experiences of distant peoples in impeccable metropolitan French, and who found readers both in their newly independent countries and in France itself what are now called the post-colonial writers. France also exports its culture around the world through the Lyce Franais system.

For some readers, the word literature may have taken on a somewhat forbidding sound from its appearance in syllabuses and exam specifications. Sadly, many people now think of literature as the kind of thing one has to read for an exam, rather than something one might read or listen to from choice. Literary texts, they think, live in hardback books with introductions and footnotes. Though nowadays they often do, it is important to realise that none of them began their lives in this way, and not a single one of them was written to be examined on. I like to imagine Rabelais chuckling incredulously in his grave at the thought of university students answering exam questions on his stories.

I shall be trying in this book to give a sense of how the texts of the various periods took shape, what sorts of audiences they were aimed at and how they were received. I shall, obviously, have to pick out a relatively small number of authors, and shall try to show why they were the most admired in their day or afterwards, and what we can gain from reading them today. Almost every sentence here will be a generalization which specialists in the author or period discussed would want to question or qualify. This is inevitable, given the number of subjects to be covered in such a short space. Each chapter will have a small number of illustrative extracts, with accompanying English translation. The translations are my own, and are sometimes quite free deliberately so. I shall also try, particularly in some of the illustrative texts, to show some of the ways in which readers used literature in their own lives and in their relations with other people.