1: The Middle Ages until circa 1400

Frits van Oostrom

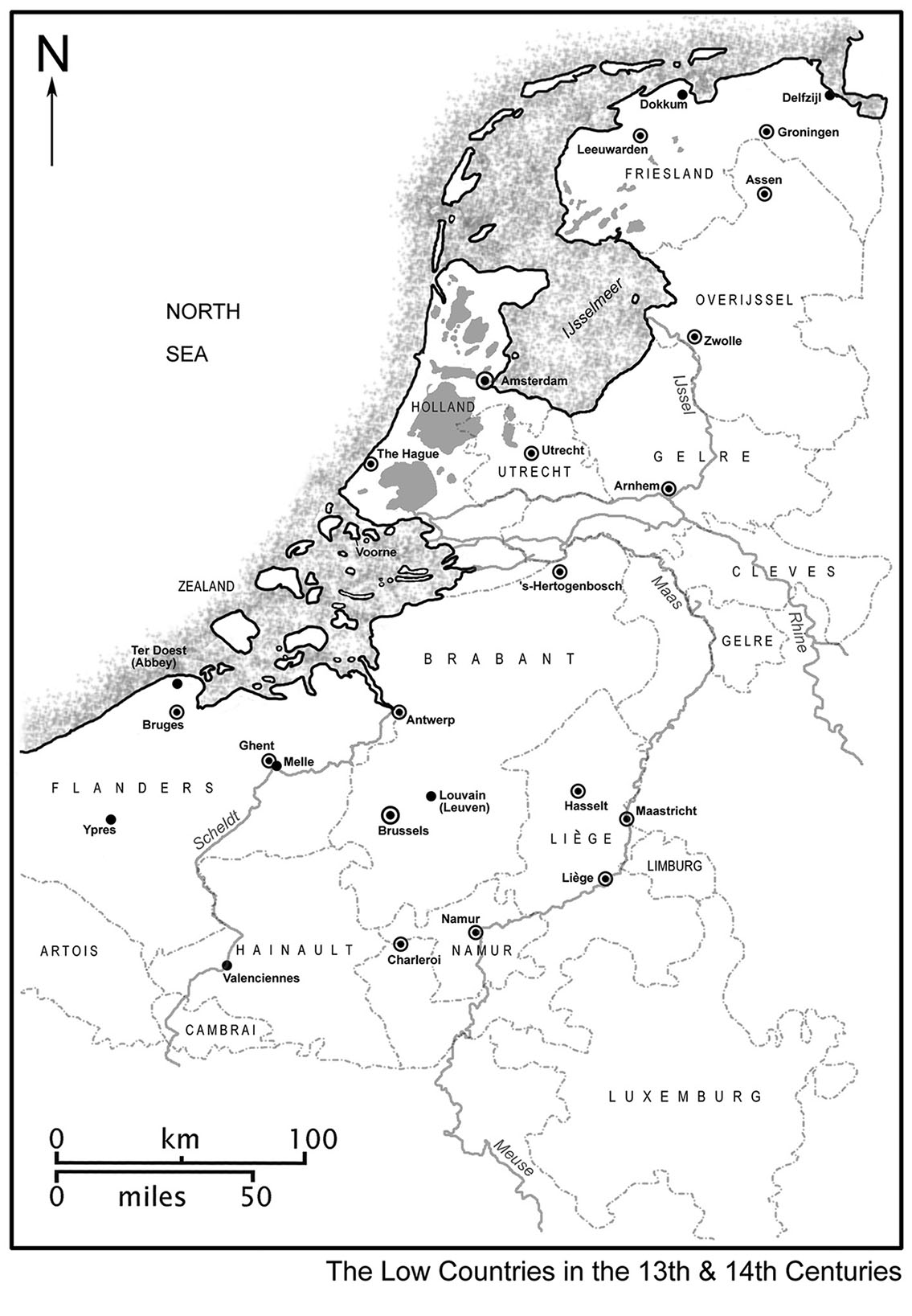

T he history of literature in Dutch begins with a poet who is known to us only from secondary sources, who belonged to both the pagan and Christian cultures, and who sang both psalms and epic verse. That this first-known poet from the Low Countries, Bernlef, was afflicted with blindness endows him with a certain Homeric quality so there is every reason to choose him as the starting point of this literary history.

Bernlef

In his hagiographical life of the eighth-century Christian preacher Liudger, who died while doing Gods work in 809, the Frisian bishop Altfried (died 849) relates that this man of God, while traveling through Friesland to spread the gospel, was once invited to share a meal with a noblewoman in a village near Delfzijl. And behold: while he and his followers were seated at the table, a blind man, one Bernlef, was brought before him, who was much loved by all the neighbors for his striking good nature, and for the marvelous way in which he sang about the heroic deeds and the wars of the Frisian kings. But this man had been struck down three years earlier with total blindness, which deprived him permanently of even the smallest ray of light. Naturally, Saint Liudger was able to restore Bernlefs sight, and he explained that this blessing was in fact Gods doing. For the rest of his life, Bernlef would place his charisma in the service of his Christian mission, teaching, performing baptisms, and chanting psalms.

When he approached his end, and his wife asked him, weeping, if she would ever be able to live without him, he jested, If I can induce the Lord above to grant me a favor, you will not live much longer in this world. When she heard this, the woman was still hale and hearty, and yet she died two weeks later to keep her husband company.

This splendid story is set in the northeasternmost region of todays Dutch-speaking territory. Bernlef, the singer, was Frisian. We shall frequently be obliged to look to Friesland for the earliest written Dutch texts. Take the oldest legal texts in Dutch, for instance. Written in Friesland, they were compiled to codify the Teutonic customary law that had been observed in these regions for centuries, and that would only slowly undergo transformation into the more abstract law fashioned on the Roman model. For literary historians, this transition is almost regrettable. For although Roman law excels in cogent abstractions excellent for legal matters, but couched in the dry phraseology of clerks customary law is notable for its highly expressive, at times almost poetic, descriptions. Here are the graphic words used to describe the marriage ceremony between free Frisians: how dio frie Fresinne coem oen dis fria Fresa wald (the free Frisian woman emerged from the free Frisian forest), mit hoernes hluud ende mit bura oenhlest (to the sound of trumpets and the shouts of neighbors), mit bakena brand ende mit winna sangh (with bonfires and the singing of friends), ende hio breydelike sine bedselma op stoed (and climbed onto his bed as his bride), ende op dae bedde herres lives netta mitte manne (and used her body with the man on the bed). Some phrases possess true poetic beauty, such as those describing nightfall: als dioe sonna sighende is ende dyoe ku da klewende deth , meaning when the sun sinks down and the cows turn their hooves, that is, lumber back to the cowshed.

So Bernlef was certainly not the only Frisian poet of his time. His region was highly developed in the early period we are considering. This included cultural development, an area largely dominated, of course, by the exchange of paganism for Christianity. In Bernlefs day, great preachers, many of them from the Anglo-Saxon territories, sacrificed their lives to secure Christianitys victory. The most renowned of these is Boniface, whose martyrs death in Dokkum in 754 is one of the lieux de mmoire of Dutch culture. One or both of the parents of Bernlef, who was born c. 750, may well have heard this impressive man of God preach. That they converted to the new faith immediately upon hearing him speak is rather unlikely, given the degree to which their son would later cherish the old traditions. In fact the kind of radical conversion so favored in narratives of early saints lives, with heathens jettisoning their darkness for the new light without a second thought, was generally quite rare. In many cases Christianity gained the upper hand only very gradually, and actually coexisted with certain forms and aspects of Germanic polytheism for many years.

Bernlef himself appears to be a good example of this coexistence, since he was presented at the banquet for St. Liudger as an outstanding singer on the martial exploits of the Frisian kings. Among the Frisian elite gathered around the table especially among the more culturally minded women, perhaps; it may not have been mere coincidence that Liudger and Bernlef had been invited by a noblewoman a good discussion about true Christianity appears to have been entirely compatible with songs extolling Germanic heroism. Bernlef himself, whose fame seems to have rested largely on his superb voice, turned out, when he met Liudger, to be fully apprised of the new doctrine; the preachers inspiring words gave him the added impetus that precipitated his definite conversion rather than suddenly revealing to him the absolute truth. Meanwhile, the fact that Bernlef saw the light, quite literally, at this point in time, is certainly the pivotal element of this story; and Altfried creates the distinct impression that the poet confined his repertoire to Christian texts after that date, abandoning songs on Frisian kings for the Psalms of David.

But is this really true? Or were not the songs celebrating Germanic heroism far more tenacious, in Friesland and elsewhere, while Christianity gained ground only slowly and in fits and starts? That certainly seems a reasonable assumption, though it is also a frustrating one, since not a scrap has been preserved of the centuries-long tradition of Germanic literature before, in, and undoubtedly after Bernlefs day and the hundreds, if not thousands, of texts of which it must have been composed. We have nothing either by Bernlef or by any of the numerous bards like him. The situation illustrates the difference between medieval and modern concepts of literature. To us, literature is wholly and inextricably tied to books. But in the Middle Ages, certain prominent forms of verbal artistry existed quite separately from books, however inconvenient it may be for literary historians who, without books, are left empty-handed. At the same time, the Middle Ages have given us so many literary books that historians are hard put to deal with them all. But like the life of Bernlef that has come down to us indirectly, these extant texts emanate in the first place from the culture of Christianity, which did more than anything else in Europe to produce a literature of books in the vernacular, and they were written in Latin, the lingua franca of medieval ecclesiastical culture.

Vernacular Writing and Oral Culture

The earliest recorded examples of what may be called literary Old Dutch illustrate the subordinate position of the vernacular compared to Latin. Characteristic examples include the so-called Wachtendonk Psalms, a corpus of some twenty-five psalms with a very complicated history of transmission, whose origins can be traced to the Moselle-Frankish region in or around the middle of the ninth century. Shortly afterwards, it seems, this translation of the psalms was adapted by a writer from the Lower Rhine region. Although some manuscripts present the Dutch text as a more or less independent Psalter and patriotic philologists have sometimes helped to strengthen that impression the Wachtendonk Psalms appear to have been written as an interlinear translation, that is, a Psalter in which each Latin verse was followed by a word-for-word equivalent in the vernacular. One surmises that a work of this kind would have been produced by schools, where boys of the early Middle Ages learned to read and write in Latin. Once schoolboys had mastered the alphabet, their standard elementary textbook was the Psalter. Where else was such a sublime combination to be found of syntactic simplicity, poetry, piety, and verse that was easily committed to memory? It seems obvious that in order to teach an understanding of Latin at this basic level, teachers will frequently have turned to the boys mother tongue, the vernacular they spoke at home (only to exchange it at the monastery for Latin, the language of the church). The numerous interlinear translations of the psalms appear to owe their existence to this interaction between the vernacular and Latin in medieval schoolrooms. In other words, Dutch verses of this kind were written primarily to explicate the Latin, and certainly not as independent literary creations. This does not detract from their interest to literary history, just as there is also an unmistakable charm about these lines, strung together into a ninth-century Dutch version of Psalm 1: