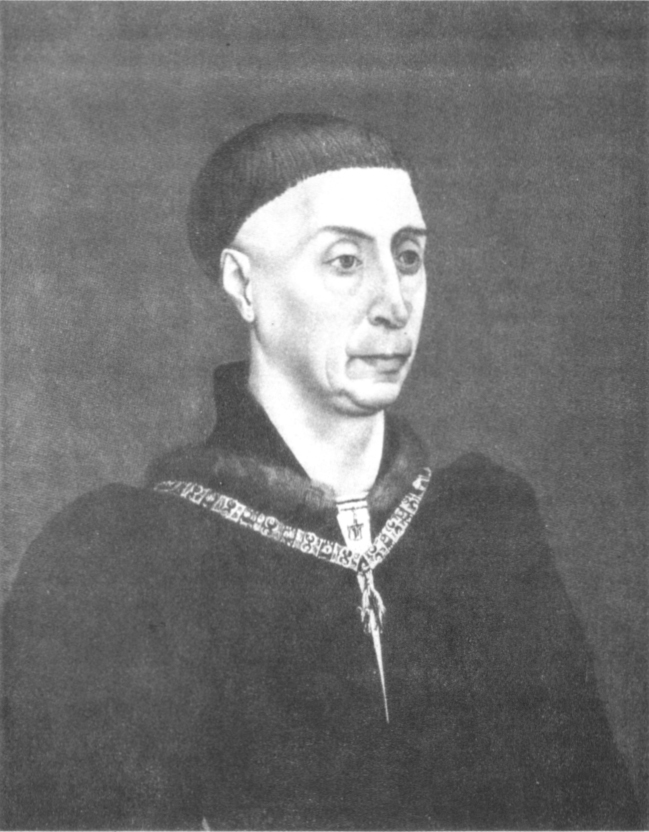

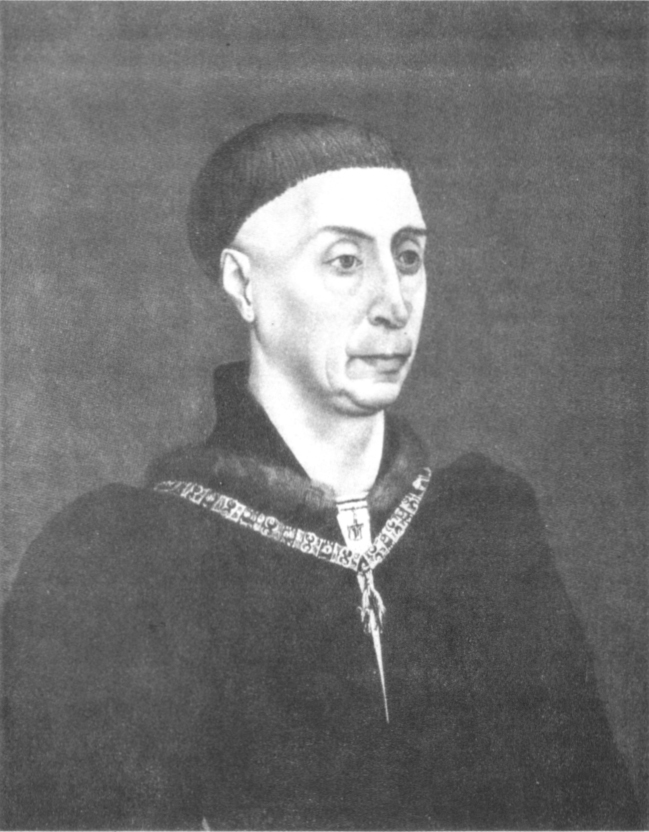

PORTRAIT OF PHILIP THE GOOD, DUKE OF BURGUNDY. BY ROGIER VAX DER WEYDEN.

The Waning of the Middle Ages

Johan Huizinga

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

Minela, New York

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 1999, is an unabridged republication of the English-language edition originally published in 1924 by Edward Arnold & Co. As stated in the authors Preface, This English edition is the result of a work of adaptation, reduction and consolidation under the authors directions. It includes, as footnotes, English translations of French and Latin poetry and prose quotations published in the original edition. Source notes not included in the English-language edition may be found in the first edition, which was published in 1919 in the Dutch language.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Huizinga, Johan, 1872-1945.

The waning of the Middle Ages / Johan Huizinga. p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-486-40443-1 (pbk.)

ISBN-10: 0-486-40443-9 (pbk.)

1. FranceCivilization1328-1600. 2. NetherlandsCivilization. 3. Civilization, Medieval. I. Title. DC33.2.H83 1999

944'.025dc21

98-31637

CIP

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

40443905 2014

www.doverpublications.com

PREFACE

History has always been far more engrossed by problems of origins than by those of decline and fall. When studying any period, we are always looking for the promise of what the next is to bring. Ever since Herodotus, and earlier still, the questions imposing themselves upon the mind have been concerned with the rise of families, nations, kingdoms, social forms or ideas. So, in medieval history, we have been searching so diligently for the origins of modern culture, that at times it would seem as though what we call the Middle Ages had been little more than the prelude to the Renaissance.

But in history, as in nature, birth and death are equally balanced. The decay of overripe forms of civilization is as suggestive a spectacle as the growth of new ones. And it occasionally happens that a period in which one had, hitherto, been mainly looking for the coming to birth of new things, suddenly reveals itself as an epoch of fading and decay.

The present work deals with the history of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries regarded as a period of termination, as the close of the Middle Ages. Such a view of them presented itself to the author of this volume, whilst endeavouring to arrive at a genuine understanding of the art of the brothers Van Eyck and their contemporaries, that is to say, to grasp its meaning by seeing it in connection with the entire life of their times. Now the common feature of the various manifestations of civilization of that epoch proved to be inherent rather in that which links them to the past than in the germs which they contain of the future. The significance, not of the artists alone, but also of theologians, poets, chroniclers, princes and statesmen, could be best appreciated by considering them, not as the harbingers of a coming culture, but as perfecting and concluding the old.

This English edition is not a simple translation of the original Dutch (second edition 1921, first 1919), but the result of a work of adaptation, reduction and consolidation under the authors directions. The references, here left out, may be found in full in the original.

Verse quotations are given in the original French throughout the work. In order to avoid an undue increase in length, quotations in prose are, as a rule, given in translations only, except in the concluding chapters where the literary expression as such is discussed, and the actual language becomes important. Here the old French prose also is set out in full.

The author wishes to express his sincere thanks to Sir J. Rennell Rodd, whose kind interest in the book gave rise to this edition, and to the translator, Mr. F. Hopman, of Leiden, whose clear insight into the exigencies of translation rendered the recasting possible, and whose endless patience with the wishes of an exacting author made the difficult task a work of friendly co-operation.

J. H.

L EIDEN

April, 1924.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Antwerp, The Museum.

From a MS. in the British Museum (after P. Durrieu, La Miniature Flamande).

From a MS. at Munich (Library of the University).

From the Death-dance printed by Guyot Marchant, Paris, 1485.

Antwerp, The Museum.

From the Calendar of theTrs riches heures du Duc de Berry, in the Muse Cond at Chantilly. (From the edition of P. Durrieu, Librairie Plon, Paris.)

Beaune, The Hospital.

Berlin, State Museum.

London, The National Gallery.

Paris, The Louvre.

Petrograd, The Hermitage.

By an Unknown Master in a MS. in the State Library, Vienna.

From the Calendar of theTrs riches heures du Duc de Berry, in the Musie Cond at Chantilly. (From the edition of P. Durrieu, Librairie Plon, Paris.)

Collection Teixeira de Mattos, Vogelenzang, Holland.

THE WANING OF THE MIDDLE AGES

CHAPTER I

THE VIOLENT TENOR OF LIFE

To the world when it was half a thousand years younger, the outlines of all things seemed more clearly marked than to us. The contrast between suffering and joy, between adversity and happiness, appeared more striking. All experience had yet to the minds of men the directness and absoluteness of the pleasure and pain of child-life. Every event, every action, was still embodied in expressive and solemn forms, which raised them to the dignity of a ritual. For it was not merely the great facts of birth, marriage and death which, by the sacredness of the sacrament, were raised to the rank of mysteries; incidents of less importance, like a journey, a task, a visit, were equally attended by a thousand formalities : benedictions, ceremonies, formulae.

Calamities and indigence were more afflicting than at present; it was more difficult to guard against them, and to find solace. Illness and health presented a more striking contrast; the cold and darkness of winter were more real evils. Honours and riches were relished with greater avidity and contrasted more vividly with surrounding misery. We, at the present day, can hardly understand the keenness with which a fur coat, a good fire on the hearth, a soft bed, a glass of wine, were formerly enjoyed.

Then, again, all things in life were of a proud or cruel publicity. Lepers sounded their rattles and went about in processions, beggars exhibited their deformity and their misery in churches. Every order and estate, every rank and profession, was distinguished by its costume. The great lords never moved about without a glorious display of arms and liveries, exciting fear and envy. Executions and other public acts of justice, hawking, marriages and funerals, were all announced by cries and processions, songs and music. The lover wore the colours of his lady; companions the emblem of their confraternity; parties and servants the badges or blazon of their lords. Between town and country, too, the contrast was very marked. A medieval town did not lose itself in extensive suburbs of factories and villas; girded by its walls, it stood forth as a compact whole, bristling with innumerable turrets. However tall and threatening the houses of noblemen or merchants might be, in the aspect of the town the lofty mass of the churches always remained dominant.

The contrast between silence and sound, darkness and light, like that between summer and winter, was more strongly marked than it is in our lives. The modern town hardly knows silence or darkness in their purity, nor the effect of a solitary light or a single distant cry.

Next page