the Last Knight

Selected titles by Norman F. Cantor

Antiquity

In the Wake of the Plague: The Black Death and the World It Made

The Civilization of the Middle Ages

Inventing the Middle Ages

Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages

Imagining the Law

Medieval Lives

The Medieval Reader

The Sacred Chain: The History of the Jews

The American Century

Inventing Norman Cantor (a memoir)

NORMAN F. CANTOR

the

Last Knight

THE TWILIGHT OF THE

MIDDLE AGES AND THE BIRTH

OF THE MODERN ERA

PICTURE EDITOR: JUDY CANTOR

FREE PRESS

NEW YORK LONDON TORONTO SYDNEY

FREE PRESS

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Copyright 2004 by Norman F. Cantor

All rights reserved,

including the right of reproduction

in whole or in part in any form.

FREE PRESS and colophon are

trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information regarding special discounts for bulk purchases,

please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales:

1-800-456-6798 or business@simonandschuster.com

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Control Number: 2003069700

eISBN-13: 978-1-439-13758-1

ISBN-13: 978-0-743-22688-2

www.SimonandSchuster.com

To my family

Acknowledgments

I wish to thank Ms. Dee Ranieri for typing the manuscript and preparing the disk for the publisher.

My literary agent, Alexander Hoyt, and my editor at Free Press, Bruce Nichols, have been very helpful in shaping the manuscript.

Contents

Introduction

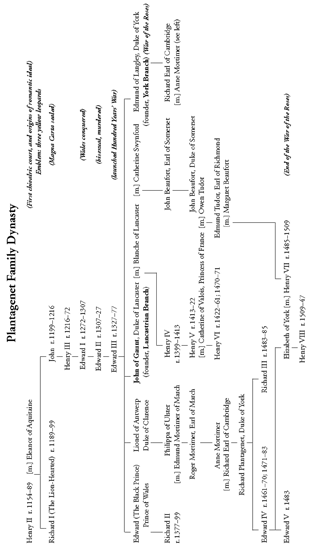

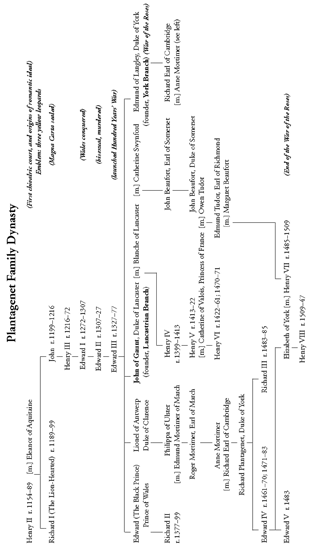

JOHN OF GAUNT, Duke of Lancaster, and in the last eight years of his life also Duke of Aquitaine, was born in 1340 and lived until 1399. Thus at his death he was quite old for someone of his generation, particularly a male engaged in warfare. Fighters of his generation rarely lived past their fiftieth birthday. Although John of Gaunt was the second surviving son of King Edward III, he inherited the Lancaster title and fabulous properties not from his father but from his father-in-law, the first Duke of Lancaster, who died in 1363.

Thereby John of Gaunt became the richest man in Western Europe who was not a crowned head (it is impossible to separate crown lands of the English and French monarchies from their personal possessions). At least three hundred lords and gentry were personally loyal, under written contracts called indentures, to the Duke of Lancaster. Gaunt had vast landholdings, especially in the north of England, and the finest house in London. He ruled over thousands of peasants.

Two of the best epic romances written between 1150 and 1400 were Lancelot, or the Knight of the Cart, written in northern France around 1180 by Chrtien de Troyes, and a work of unkown authorship called Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, written in central England around 1375. What do these works tell us about the world of John of Gaunt?

In each poem the hero pursues a perilous questalone, having left behind King Arthur and his Round Table. In each there are amorous adventures with beautiful women. Lancelot succumbs to the womens charms, but Gawain does not. There are also many military adventures from which Lancelot and Gawain emerge triumphant or at least get off by fighting to a draw. Both Lancelot and Gawain return in triumph to King Arthurs court. Running through both poems is a strain of sadomasochistic sexuality. There is a pronounced psychological sexual adventurism in both poems. This, along with the military adventures, is what grabbed the attention of the contemporaries who listened to these great romantic epics.

In many ways, John of Gaunt epitomized the ideals of these stories. In some ways, he surpassed them. In both Lancelot and Gawain the knights of the Round Table mount modest operations, simply described. The two knights go off on their lonely and perilous quests. In reality, John of Gaunt would travel only with many companions. The other difference in the mise-en-scne is that Gaunt lived in elaborate castles, such as his home base of Pontefract. He spent lavishly on dcor, which was much more impressive than that of the battlements occupied by Arthur and his knights. This was the age that inaugurated the building of the elaborate French chteaus. In addition to occupying palatial mansions, the high aristocracy spent lavishly on dress and diet, and on gift-giving (especially gifts from men to women), far more so than the modest and austere world the Arthurian Round Table would allow.

Casting a dark shadow, however, was what we call the Hundred Years War. It really began in the 1350s and 60s. That period was followed by thirty years or so of long truces. The war flared up again the second and third decades of the fifteenth century, to be followed by the ignominious expulsion of the English monarchys forces from all but one port city in France. Joan of Arc is alleged to have played a significant role in that expulsion.

Meanwhile, for long periods, much of the western third of France was ravaged by the English lords and knights. Even when there were no military campaigns under way, the French countryside and towns were heavily affected by guerrilla warfare. Why should the lavishly living aristocracy of England and France, with so much to be grateful for, have gotten involved in this almost interminable conflict? Glory and greed are what motivated the nobles to undertake a century of intermittent warfare. For glory on the battlefield, they wanted to put on elaborate armor and show their valor, even though the cost of war was beyond the resources of the English and French monarchies.

Greed entered the picture as well. The English sought to keep the French out of the wine-growing region of Gascony (Bordeaux). The English sought to dominate the textile-manufacturing cities of Flanders (Belgium). Past the dazzle of burnished steel there were strategic reasons for the Hundred Years War.

Beyond the glory and greed there lay the dynastic claim of Edward III to the French crown, sheer nonsense that was taken seriously by some members of the English aristocracy, including John of Gaunt.

This was John of Gaunts worlda society of great propertied wealth for the aristocracy, where the nobility could live very well on its income. It did so in any case, but billions of dollars were drained away in warfare. The arts and humanities, higher learning and exquisite craftsmanship played significant roles in Gaunts world, though this culture did not fulfill its potential because a cloud of poisonous conflict hung over English and French society.

It was a world in which the Middle Ages were passing away and the Renaissance struggled to be born. Gaunts world was one in which great achievements in literature and the arts were partly inhibited by aspirations to military glory and the dictates of greed. It was a world in transition, and Gaunt was its central figure.

Next page