Thank you for downloading this Free Press eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Free Press and Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Contents

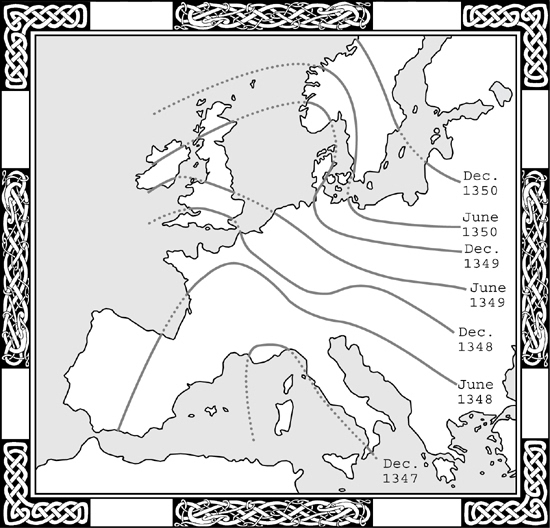

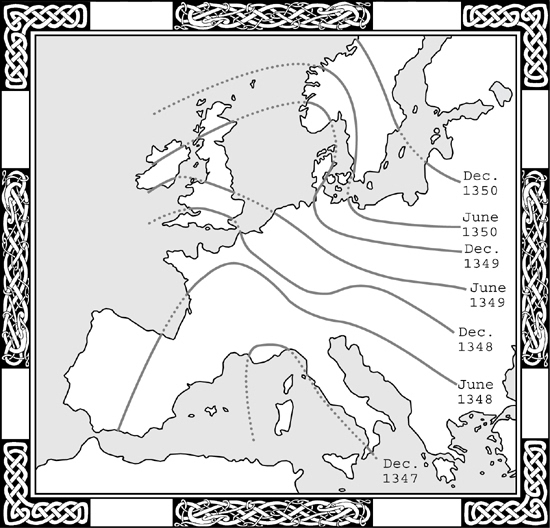

T HE SPREAD OF THE B LACK D EATH ACROSS E UROPE IN THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY.

Graham Twigg, The Black Death, 1984

To my family

PART I

Biomedical Context

CHAPTER ONE

All Fall Down

I N THE SIXTH MONTH OF the new millennium and new century, the American Medical Association held a conference on infectious diseases. Pronouncements by scientists and heads of medical organizations at the conference were scary in tone. Infectious disease was the leading cause of death worldwide and the third leading cause in the U.S.A., it was stressed. The situation could soon become much worse.

As the world becomes more of a global village, said one expert, infectious disease could by natural transmission become more threatening in the United States. Here monitoring is lax because of a mistaken belief that the threat of infectious disease has been almost wiped out by antibiotics.

Bioterrorism presented a further and much greater possibility of terrible outbreaks of pandemic in the United States. The New York Times reported: A speaker at the meeting warned that the healthcare system in the United States was not prepared for a bioterrorist attack, in which hundreds or thousands of people might flood hospitals, needing treatment for diseases: anthrax, plague, or smallpox, which most doctors in this country have never seen.

In the same week as this AMA conference and its Cassandra-like speeches, the NBC Nightly News featured a brief segment showing American biochemists helping their Russian counterparts clean up and close down a large germ warfare factory. The TV correspondent remarked that the Russian plant had been capable of producing far more than the minimum required for effective biochemical warfare. He did not pursue the obvious questions of whether the Russians had been exporting the plants surplus to Iraq, or if this was only one of several Russian germ warfare factories and whether the others may still be operating.

That The New York Times report was tucked away on page fifteen of its National Edition and that NBC News devoted all of four minutes to the Russian disease factory indicate that the problem of infectious disease and its pandemic threat to American wellbeing is still regarded as a marginal matter. By the time the next president of the United States finishes his term, it could be the most visible problem facing American society, similar to the biomedical crisis of late medieval Europe, England in particular.

In the England of 1500 children were singing a rhyme and playing a game called Ring Around the Rosies. When I grew up in Canada in the 1940s children holding hands in a circle still moved around and sang:

Ring around the rosies

A pocketful of posies

Ashes, ashes

We all fall down

The origin of the rhyme is the flulike symptoms, skin discoloring, and mortality caused by bubonic plague. The children were reflecting societys efforts to repress memory of the Black Death of 134849 and its lesser aftershocks. Childrens games wereor used to bea reflection of adult anxieties and efforts to pacify feelings of fright and concern at some devastating event. So say the folklorists and psychiatrists.

The meaning of the rhyme is that life is unimaginably beautifuland the reality can be unbearably horrible.

In the late fourteenth century a London cleric, who previously served in a rural parish and who is known to us as William Langland, made severe reference to the impact of infectious diseases pocks (smallpox) and pestilence (plague) in Piers Plowman, a long, disorganized, and occasionally eloquent spiritual epic. As translated by Siegfried Wenzel:

So Nature killed many through corruptions,

Death came driving after her and dashed all to dust,

Kings and knights, emperors and popes;

He left no man standing, whether learned or ignorant;

Whatever he hit stirred never afterwards.

Many a lovely lady and their lover-knights

Swooned and died in sorrow of Deaths blows....

For God is deaf nowadays and will not hear us,

And for our guilt he grinds good men to dust.

The playing children, arms joined in a circle and singing Ring Around, and the gloomy, anguished London priest were each in their distinctive ways trying to come to psychological terms with an incomparable biomedical disaster that had struck England and most of Europe.

The Black Death of 134849 was the greatest biomedical disaster in European and possibly in world history. Its significance was immediately perceived by the wise Arab historian Ibn Khaldun, writing a few years later: Civilization both in East and West was visited by a destructive plague which devastated nations and caused populations to vanish. It swallowed up many of the good things of civilization and wiped them out in the entire inhabited world. A contemporary Florentine writer referred to the exterminating of humanity.

A third at least of Western Europes population died in what contemporaries called the pestilence (the term the Black Death was not invented until after 1800). This meant that somewhere around twenty million people died of the pestilence from 1347 to 1350. The so-called Spanish influenza epidemic of 1918 killed possibly fifty million people worldwide. But the mortality rate in proportion to total population was obviously relatively small compared to the impact of the Black Deathbetween 30 percent and 50 percent of Europes population.

The Black Death affected most parts of the Mediterranean world and Western Europe. Ingmar Bergmans 1957 film The Seventh Seal depicts the impact of the Black Death on Sweden. In Bergmans view the Black Death, which reached Sweden by 1350, caused an era of intense pessimism and widespread feelings of dread and futility.

But the great medical devastation hit no country harder than England in 134849 and because of the rich documentation surviving on fourteenth-century England it is in that country that we can best examine its personal and social impact in detail. Furthermore, there were at least three waves of the Black Death falling upon England over the century following 1350, nowhere near as severe as the cataclysm of the late 1340s, whose severity was unique in human history. But the succeeding outbreaks generated a high mortality nonetheless.

The population of England and Wales in the thirteenth century had doubled. Unusually warm weather together with adequate moisture produced bumper crops and the generous food supply moderated the death rate. Then the downswing of the Malthusian cycle common to premodern rural societies set in.

Due to famines in the second decade of the fourteenth century the English population had begun to recede from its medieval peak of six million in 1300. But it was the Black Death that principally caused the demographic crash and the road back was slow and very long. When the English population began to rise significantly in the later seventeenth century there was yet another and final outbreak of the terrible pestilence in 1665 as graphically imagined by the journalist Daniel Defoe (author of Robinson Crusoe ) in his Journal of the Plague Year (1722).

Next page