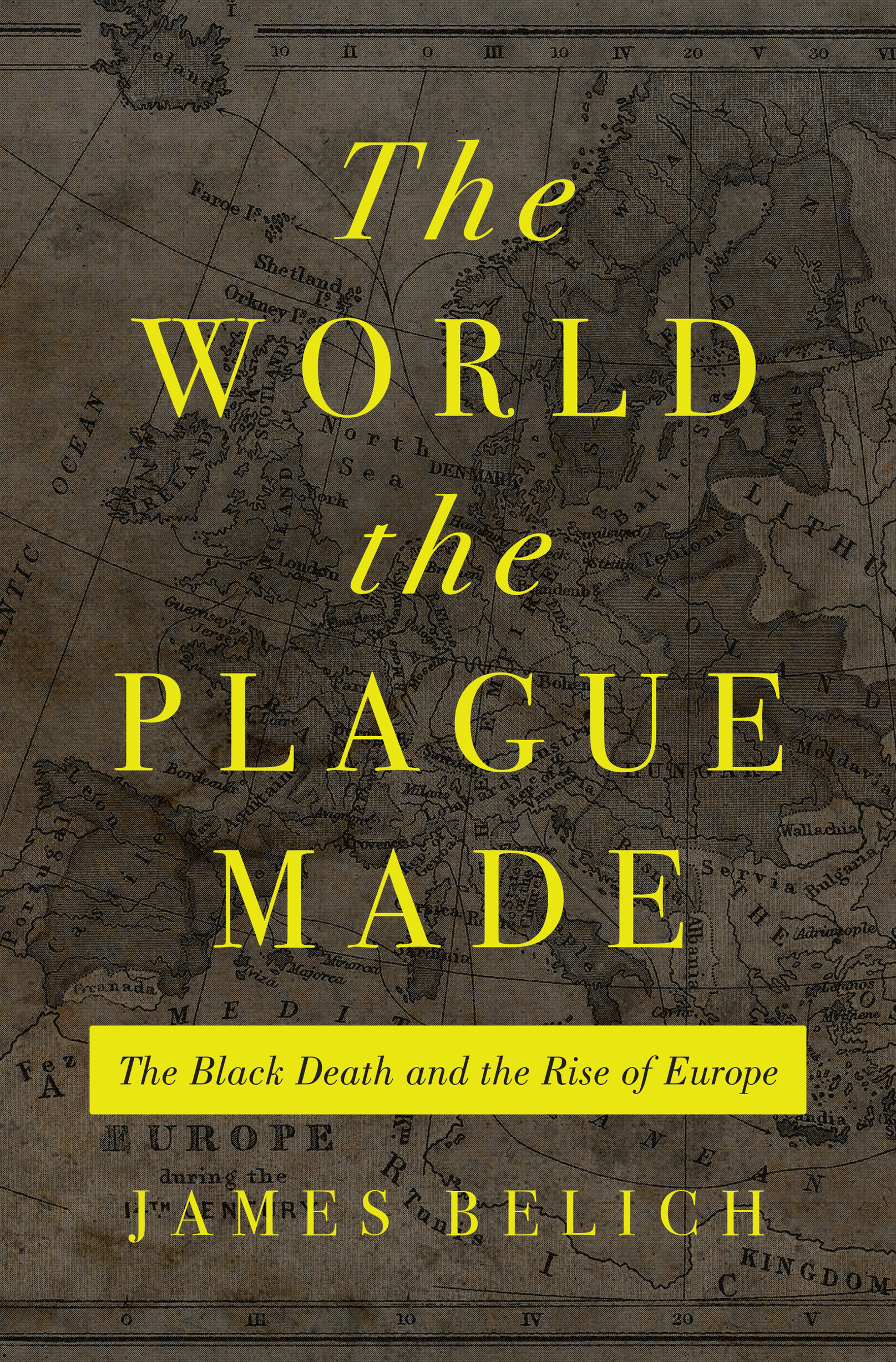

THE WORLD THE PLAGUE MADE

The World the Plague Made

THE BLACK DEATH AND THE RISE OF EUROPE

JAMES BELICH

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON & OXFORD

Copyright 2022 by James Belich

Princeton University Press is committed to the protection of copyright and the intellectual property our authors entrust to us. Copyright promotes the progress and integrity of knowledge. Thank you for supporting free speech and the global exchange of ideas by purchasing an authorized edition of this book. If you wish to reproduce or distribute any part of it in any form, please obtain permission.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

99 Banbury Road, Oxford OX2 6JX

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 9780691215662

ISBN (e-book) 9780691222875

Version 1.0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022935399

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Ben Tate and Josh Drake

Production Editorial: Karen Carter

Jacket Design: Karl Spurzem

Production: Danielle Amatucci

Publicity: Carmen Jimenez and Alyssa Sanford

Copyeditor: Karen Verde

Jacket/Cover Credit: Courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, the University of Texas at Austin

CONTENTS

- ix

MAPS

THE WORLD THE PLAGUE MADE

Introduction

PLAGUE PARADOXES

IN 1345, Europe and its neighbours were beset by a terrible plague. In proportion to population, it may have been the most lethal catastrophe in human history. It appeared first in the Black Sea/Volga region, spread throughout the Mediterranean from 1347, and swept Northern Europe in 1348, though it did not reach some Russian regions until as late as 1353. Once known as the Great Death, The Great Plague, or simply The Death or The Plague, it came to be called The Black Death. Its horrors and terrors defy description, though evocative chroniclers came close. Some variants killed quickly, in a day or two; the main variant took a week or so from the first appearance of symptoms. Sufferers lay in agony, their kin sometimes reluctant to nurse them for fear of infection. Uninfected children died because their parents had done so; infants suckling the breasts of dead mothers. Medics did their best, as shown by their numerous plague tracts, but could find no effective treatment. Francesco Petrarch, voice of the early Italian Renaissance, wrote: Our former hopes are buried with our friends. The year 1348 left us lonely and bereft, for it took from us wealth which could not be restored by the Indian, Caspian or Carpathian Sea. Last losses are beyond recovery, and deaths wound beyond cure. There is just one comfort: that we shall follow those who went before.

New information about the Black Death requires four revisions to our understanding of it. The case for each is made in part one. Here we briefly consider their possible implications. The first is less a revision than the restoration of an older view. During the twentieth century, most experts were convinced that the Black Death was bubonic plague, caused by the bacteria Yersinia Pestis (Y. Pestis), which normally infected only wild rodents. Between 2001 and 2011, the notion that the plague was bubonic came under serious attack, but recent science has now decisively reaffirmed it. This confirms that the Black Death kicked off the second of three known bubonic plague pandemics. Pandemic technically means a single vast epidemic, but in common usage has come to mean a series of plague epidemics in the same large space. It is important that we distinguish them from one-off plague epidemics and from regional and local outbreaksthe last at least were, and are, quite common. The First Pandemic was the early medieval Plague of Justinian, the reigning Byzantine emperor, which hit much the same region as the late medieval Black Death, but eight centuries earlier, in 541. Subsequent strikes, 17 or 18 of them, persisted for two centuries. The Black Death Pandemic, beginning in 1345, persisted for more than three centuries and involved about 30 major epidemics in all. The third, or modern, pandemic went intercontinental from southeast China in 1894, reached all six habitable continents, and declined from 1924. We draw much of our information about plague from this last pandemic, but it was much shorter, more pan-global, and proportionately far less lethal than the previous two. So the Second Plague Pandemic was a rare event, with only one generally accepted precursor and no real successor. If random curveballs from nature ever affected the course of human history over the past two thousand years, the Black Death pandemic is a candidate.

This is even more so because of the Black Deaths horrifyingly high mortality, our second revision. The standard estimate for the first strike, 134653, is between one-quarter and one-third of the population of Western Europe, say 30%bad enough in anyones terms. Many scholars have found this unconvincingly high, given the fact that the Third Pandemic killed no more than 3% in the worst afflicted regions. Yet new and reinterpreted evidence suggests that the real Black Death toll was more like 50%: a sudden halving in the first strike alone. It may seem macabre to dispute the details of so terrible a tragedy: what does it matter if death took a third or a half? But humans are resilient, and the difference could be important to the survivors. If harvests decline 40% and 30% of people die, there is dearth for the living. If 50% die, they have modest abundance. Our third revision concerns the timing of population recovery. None of the later strikes had the spread or lethality of the first one, and, until recently, recovery was thought to be quite rapid, beginning by 1400 and complete by 1500. It now seems that this is about a century out: demographic recovery was not general until about 1500, and was not complete until about 1600. England recovered its pre-plague population in 1625, after 275 years. So, during the fifteenth century, Western Europe still had half its normal populationthe level before 1345 and after 1600. Yet this is the very century in which Western Europes global expansion began.

Why Europe? Why did this small continent expand to the point of global hegemony? In 1400, Western Europeans controlled around 5% of the planets surface. They are said to have controlled about 35% by 1800, reaching 80% by 1900. Territory is a crude measure, and we will see that substantive European control was exaggerated. But, even by 1550, with population recovery still incomplete, Europeans dominated South Americas richest bullion sources and had begun to settle in other parts of the Americas. They were also major players in the sub-Saharan African gold and slave trades, as well as in the dynamic mercantile activity of the Indian Ocean, and were beginning to stretch to China too. The wealth of Petrarchs ocean seas proved, after all, to be of some comfort to plagues survivors. This strange intersection of depopulation and successful expansion is plagues first paradox.

Geographic expansion, beginning in the fifteenth century and culminating in global hegemony in the nineteenth, was only one-half of Europes Great Divergence from the rest of the planet. The other half was economic development, culminating in industrialisation in the later eighteenth century. China and India were the global economic leaders in the High Middle Ages (c.9001300 CE), and the point at which Europe began to catch up on them is disputed. But a case will be made, in part two of this book, for the post-plague era, 13501500. This conjunction of terrible epidemics with economic and technological advance is plagues second paradox, which brings us to our fourth and final plague revision. Many authorities still believe that the Black Death pandemic also hit India and China in the fourteenth century, as well as Europe and its neighbours. Part one will suggest that this was probably not the case. This may implicate plague in the Great Divergence. To oversimplify for emphasis (and to preempt a possible quip), this book tests a new two-word answer to an old two-word question: Why Europe?