A LSO BY P ATRICK C OCKBURN

The Occupation: War and Resistance in Iraq

The Broken Boy

Out of the Ashes: The Resurrection of Saddam Hussein

(with Andrew cockburn)

SCRIBNER

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Copyright 2008 by Patrick Cockburn

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Scribner Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

SCRIBNER and design are registered trademarks of The Gale Group, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, Inc., the publisher of this work.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN-13: 978-1-4165-9374-4

ISBN-10: 1-4165-9374-8

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

http://www.SimonSays.com

To Janet, Henry, and Alexander

Contents

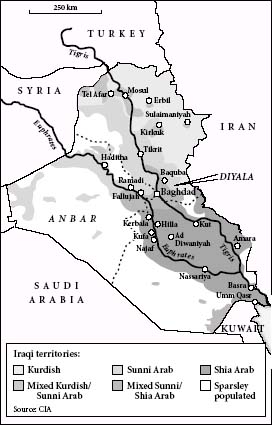

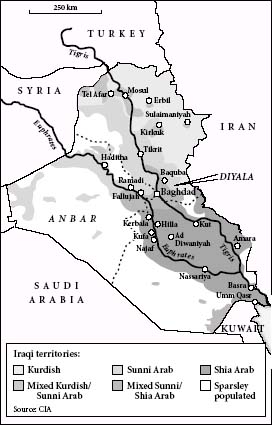

Iraq and Its Ethnic and Religious Groups

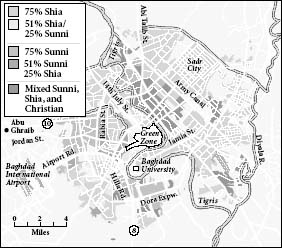

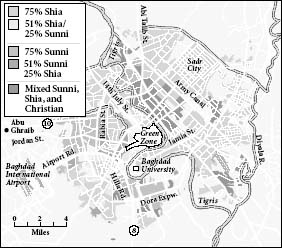

Religious Divisions in Baghdad, November 2007

MUQTADA

CHAPTER ONE

The Road to Kufa

Hes an American spy! shouted the Mehdi Army militiaman as he leaned in the window of my car and grabbed the red-and-white kaffiyeh, the Arab headdress, I was wearing as a disguise. It was April 19, 2004, and I was trying to get to the holy city of Najaf, where Muqtada al-Sadr, the mysterious Shia cleric whose men had seized much of southern Iraq earlier in the month, was under siege by American and Spanish troops. A U.S. general had said he would be killed or captured. I was wearing the kaffiyeh because the sixty-three-mile-long road from Baghdad to Najaf passes through a string of very militant and very dangerous Sunni towns where foreigners had been attacked. I have fair skin and light brown hair, but I had hoped that the headdress might convince anybody glancing at the car that I was an Iraqi. It was not intended for close inspection.

I should have been more wary. I was traveling in a white Mercedes-Benz of a type not very familiar in Iraq that might easily have attracted attention. I sat in the back to be less conspicuous. In the front passenger seat was Haider al-Safi, a highly intelligent and coolheaded man in his early thirties who was my translator and guide. An electrical engineer by training, he had run a small company fixing photocopying machines in the years before the fall of Saddam Hussein. He lived in the ancient Shia district of Khadamiyah in Baghdad, site of one of the five great Shia shrines in Iraq. He neither drank nor smoked but was otherwise secular in outlook. My driver was Bassim Abdul-Rahman, a slightly older man with close-cropped hair. A Sunni from west Baghdad, he had shown he had good nerves ten days earlier, when we were caught in the ambush of an American fuel convoy near Abu Ghraib on the road to Fallujah. All three of us had got out of the car and lain on the ground until there was a break in the firing, when Bassim had driven us slowly and deliberately past bands of heavily armed villagers running to join the fight. I crouched down in the back of the car hoping they did not recognize me as a foreigner.

We had come across the Mehdi Army militiamen in their black shirts and trousers as we approached the city of Kufa on the west bank of the Euphrates River, a few miles from Najaf. They were standing or sitting cross-legged in the dust beside the road where it turned off to Kufa before crossing the bridge over the river. They were well-armed young men, carrying Kalashnikov assault rifles, with rocket-propelled grenade launchers slung across their backs and pistols stuck in their belts. Many had ammunition belts filled with cartridges crisscrossed over their chests. There were too many of them for a normal checkpoint. They were edgy because they expected U.S. troops to attack them at any minute. In the distance, to the north, I could hear the distant pop-pop of gunfire along the Euphrates.

Checkpoints in Iraq did not at this time have the reputation they later gained of being places of terror, often run by death squads in or out of uniform, looking for somebody to torture and kill. Probably we were too relaxed, because the worst danger seemed to be behind us in the grim towns of Mahmudiyah, Iskandariyah, and Latafiyah, where permanent traffic jams gave passersby plenty of time to look us over. There was also a truce. It was the Prophets birthday and Muqtadas spokesman in Najaf, Sheikh Qais al-Ghazali, had declared that there would be no fighting with the Americans for two days in honor of the event and to protect the pilgrims flooding into the city to celebrate it. I had lived long enough in Lebanon during the civil war to have a deep suspicion of truces. When they were declared, as happened frequently, I used to jokingly tell friends: Its all over bar the shooting, so keep your head down. True to form, we could already hear the menacing crackle of machine-gun fire coming from somewhere in the date palm groves around Kufa. But the sound was still intermittent and far away, and was not discouraging the thousands of enthusiastic Shia pilgrims I could see marching on both sides of the road, banging their drums and waving green and black flags as they walked to the shrine of Imam Ali in Najaf. One of the most surprising and attractive aspects of the new Iraq was the popularity among the Shia of pilgrimages, which had been banned or limited in number by Saddam Hussein.

Haider told Bassim to stop so we could ask the militiamen if we were on the right road to Kufathey would know if the Americans were firing on the roadand if they had heard anything about a press conference being given by Qais al-Ghazali. They were immediately suspicious. Some ran to the car and started staring at me. It was then that one of them started to yell: This is an American! This is a spy! Things then got worse very fast. They dragged me out of the car and started handing around the kaffiyeh to one another as evidence of guilt. Haider was trying to say I was Irish and a journalist. It did no good. Other militiamen took up the shout: He is an American! He is an American! Two of the militiamen turned on Haider and said: How dare you bring him to the shrine of Imam Ali. Haider protested he came from a family of sayyids, descendants of the Prophet Mohammed, and furthermore his family originally came from Najaf.

The Mehdi Army men started to go through my brown shoulder bag. I had bought it in Peru three years earlier because it was exactly the right size for carrying the small number of items necessary for a journalist. They found the contents very incriminating as they took out a notebook; a Thuraya satellite phone, which looked like a large black cell phone; and a camera. For some reason cameras have always been regarded with deep suspicion by Iraqis as evidence of espionage. The militiamen waved it around saying that I wanted to photograph them and send the photos to the Americans who would then arrest them. They started to push me around and one of them kicked me. I thought they were working themselves up to kill us. Bassim thought so, too. I believe that if Patrick had an American or English passport they would have killed us all immediately, he said later.

One of the militiamen was peering at me suspiciously and suddenly sniffed. He pointed at me and said: He is drunk; he drank alcohol before coming here. A second Mehdi Army man turned on Haider and accused him of drinking alcohol with foreigners. Bridling at this, Haider, who was losing no chance to stress his Shia credentials, shot back: How dare you accuse me of coming to the Holy City drunk when I dont drink and come from a sayyids family? If I was drunk you would smell the alcohol.

![Cockburn Patrick - Syria Burning: A Short History of a Catastrophe: [VersoUSAed]](/uploads/posts/book/207719/thumbs/cockburn-patrick-syria-burning-a-short-history.jpg)