Many of the primary sources consulted for this book do not consistently apply English spelling, grammar, or capitalization. Original usage and formatting has been retained as frequently as sense allowed. In order to help distinguish these idiosyncracies from transcription errors, they are indicated with a [ sic ] mark. Where texts have been altered, the changed text is indicated by its insertion in square brackets.

The author takes responsibility for any typographical errors within this text.

Portions of many (though not all) of the documents discussed in this book have been transcribed and can be consulted digitally (in English or French) on the Death on a Painted Lake: The Tom Thomson Tragedy website, part of the Great Unsolved Mysteries in Canadian History project.

The MacCallum and Thomson collections, along with smaller deposits in other publicly accessible archives (such as the archives of Trent University in Peterborough, Ontario, which hold the diary of Mark Robinson, the park ranger who led the search for Thomson), allow reasonably clear sense to be made regarding what was happening at Canoe Lake in the spring and summer of 1917.

For more information on specific sources, please see A Note on the Sources and Selected Bibliography at the end of this work.

Introduction

The Misunderstood Death of Tom Thomson

Except to a very limited number of friends, Tom Thomson is a remote and mystical figure that broke into the art firmament with a sudden and dazzling brilliancy, and then disappeared as suddenly into the unknown. During the last decade his career has been wrapped in mists of mystery and half truths somewhat obscuring a clear vision of the man and his work.

A.H. Robson, Tom Thomson , 1937

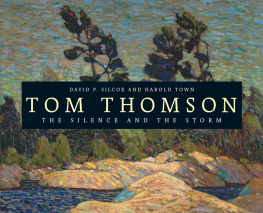

By almost any measure , Tom Thomson can be regarded as a Canadian national icon. His name is synonymous with artistic skill, love of the wilderness, and national pride. His paintings have become a standard reference point; canvases such as The West Wind and The Jack Pine whether seen as originals or reproductions, in coffee-table books or calendars, on T-shirts or postcards or coffee mugs are among the most easily and widely recognized Canadian artworks.

Along with his paintings, Thomsons fame rests upon his reputation as a model Canadian. He is memorialized as a skilled yet modest artist, quiet but confident, capable in rough outdoor skills such as fishing and canoeing yet possessing the sensitivity of an artist. He is recalled as a man who gave up days working in a Toronto office to follow his passion for the lonely, lovely lakes of Algonquin Park.

Thomson exhibited his first painting in 1913 and died four years later. By the mid-1920s, he was being hailed as one of Canadas most visionary artists. In the 1940s, novelist Hugh MacLennan included Thomson in his list of the top ten Canadians, beside towering personalities such as explorer Samuel de Champlain; Canadas first prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald; and Sir Frederick Banting, the discoverer of insulin.

Today Thomson is most often mentioned in association with Canadas Group of Seven, despite having died three years before its formation. As the Groups artistic reputation grew during the 1920s, key members recognized his role in their artistic development. Their public statements of respect served to cement his reputation to theirs, elevating Thomson to a place equivalent to being an eighth, deceased member of the Group. In some of the early international exhibitions featuring their work, Thomsons pieces were given a very prominent position.

While he was alive, Thomsons art was not exhibited outside Canada. The most he was paid for a painting was five hundred dollars. Almost one hundred years later, Thomsons artworks have been the subject of high- profile international exhibitions in London and Moscow, and have sold for over one million dollars at auction.

Tom Thomson and his artwork have worked their way into every nook and cranny of Canadians cultural sensibilities, from the highest of cultural institutions to the most low-brow of kitsch. He has been the subject of plays, rock songs, books of poetry, films, and parlour games.

That a landscape painter has achieved such a level of fame is rather amazing given that he only painted seriously for about five years. It might also come as a surprise that, during that brief period, his paintings were not generally seen as the product of unique genius and insight. He first took up work in the arts as a designer, and his early efforts at painting were considered dull. Even his circle of friends and supporters saw that his painting might benefit significantly with help from more experienced, formally trained artists.

Assistance from his friends did not necessarily lead to widespread commercial and critical success. The works created by Thomson and his peers received many colourful, less-than-friendly assessments. In 1916, Toronto critic Hector Charlesworth suggested their paintings were closer to gobs of porridge than works of art, and their purposeless medley of crude colours evoked comparisons to the contents of a drunkards stomach.