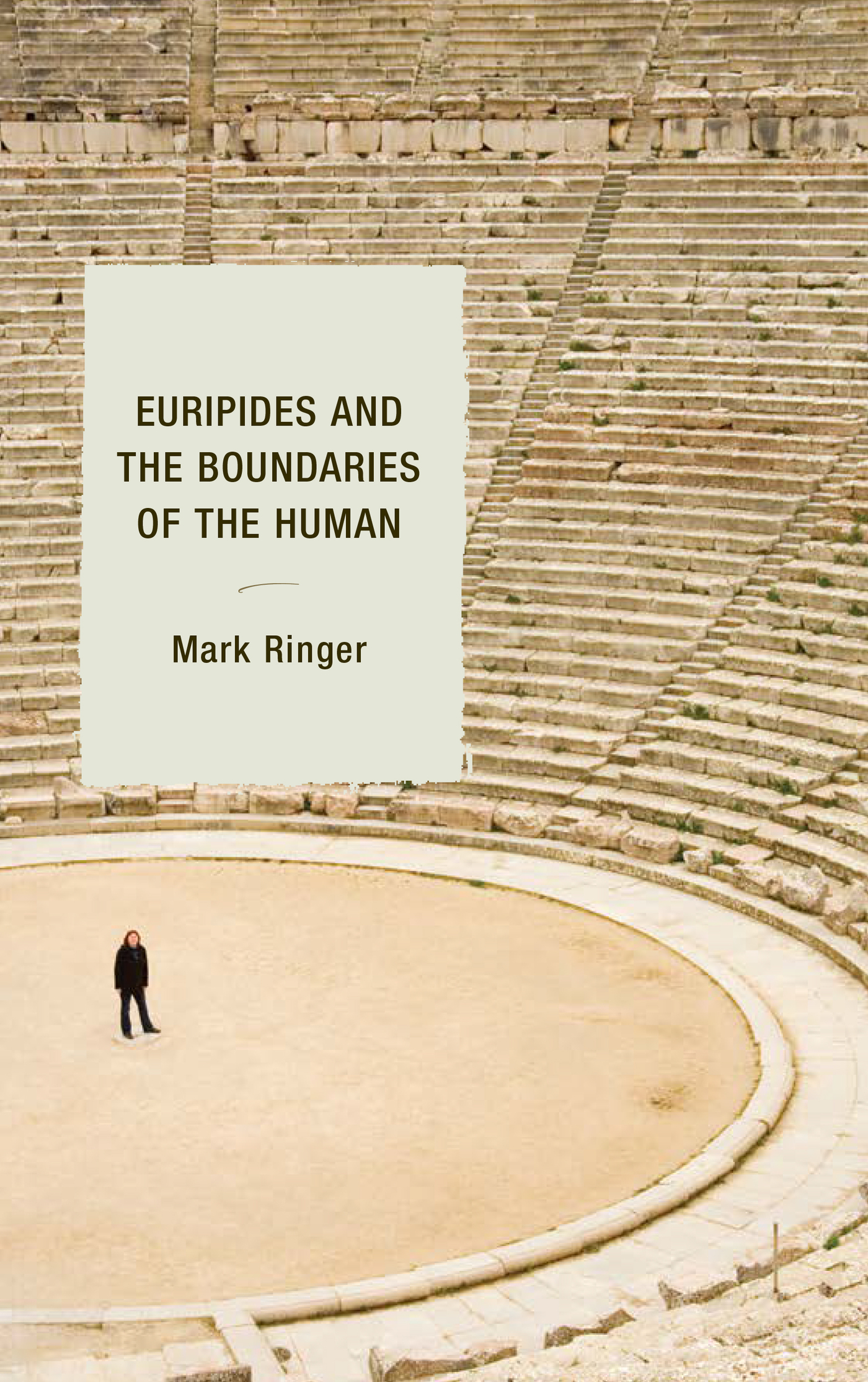

Euripides and the Boundaries

of the Human

Euripides and the Boundaries

of the Human

Mark Ringer

LEXINGTON BOOKS

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Lexington Books

An imprint of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright 2016 by Lexington Books

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ringer, Mark, author.

Title: Euripides and the Boundaries of the Human / Mark Ringer.

Description: Lanham : Lexington Books, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016026932 (print) | LCCN 2016028197 (ebook) | ISBN 9781498518437 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781498518444 (Electronic)

Subjects: LCSH: Euripides--Criticism and interpretation. | Greek drama (Tragedy)--History and criticism.

Classification: LCC PA3978 .R48 2016 (print) | LCC PA3978 (ebook) | DDC 882/.01--dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016026932

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

For my wife, Barbara Bosch,

my students at Marymount Manhattan College,

and the memory of my teacher, Irving E. Cox, Jr. (19172001),

who cared that the Greek Classical Heritage survives.

From Goethes poem, Grenzen der Menschheit

(Boundaries of Mankind)

A human must never

Measure themselves against gods.

Even if a man

Touches the starry heavens

With his head,

His unsteady feet

Lose touch with the ground

And clouds and winds

Make sport of him.

Or if he stands

Strong with steady

Limbs upon the

Firm set earth,

He cannot even reach up

To compare himself

With the oak

Or the vine.

What is the difference

Between gods and humans?

The gods see before them

Unending waves

Of an eternal stream

While a single wave engulfs us

And we sink.

Preface

In Senecas 115th Epistle, the Stoic cites lines from Euripidess now lost play, Bellerophon, and describes the reception given it by a fifth century B.C. audience. The lines ran:

Money, that blessing to the race of man,

Cannot be matched by mothers love, or lives

Of children, or the honor due ones father...

Seneca reports:

When these last-quoted lines were spoken at a performance of one of the tragedies of Euripides, the whole audience rose with one accord to hiss the actor and the play off the stage. But Euripides jumped to his feet, claiming a hearing, and asked them to wait for the conclusion and see the destiny that was in store for this man who gaped after gold. Bellerophon, in that particular drama, was to pay the penalty which is exacted of all men in the drama of life.

How often Euripides must have jumped to his feet to defend himself from an audience naively capable of confusing a fictional personas remarks with the inner beliefs of the dramas author! Lest we feel superior to our ancient forbearers, it is worth considering how this particular playwright is still misevaluated to this very day.

Euripides is the playwright of boundaries. He asserts humankinds need to recall its place in the universe: the virtually unbridgeable divide of god from man, the depth of human egotism that brings disaster, and the limitations of human perception. Goethes 1781 poem, Grenzen von Menchheit, quoted above, reveals the German poets spiritual affinity and deep admiration for the Greek tragedian. Near the end of his life, Goethe cited Euripides as the greatest of all dramatists. Have all the nations of the world since his time produced one dramatist who was worthy to hand him his slippers? (Tagebcher, November 22, 1831). However, while Euripides is probably the most popular of Greek playwrights in the twenty-first century, many contemporaries would still balk at Goethes assertion of his supremacy. I do not aim to assert such superiority but only to argue that Euripidess achievement is the equal of the two other surviving Greek tragedians and that the qualities that make him so are manifest in all his surviving plays.

This book offers a play-by-play analysis of the nineteen canonical dramas attributed to Euripides, which has not been attempted in several generations due in part to the sheer number of surviving plays, but more importantly because of the conviction that the dramas are too diverse to be handled collectively. I seek to acquaint the reader with Euripidess work as an organic unity emanating from a single remarkable mind of the mid to late fifth century B.C. Taken in its entirety and in his historic context, Euripidess works reveal a theatrical genius who is both startlingly ahead of his time and deeply respectful of tradition. Within this seeming contradiction lies the heart of Euripidess dramatic and intellectual power. Received opinion is that his plays present a bewildering diversity of thought that prohibits a comprehensive play-by-play treatment of his work within a single book. However, there are elements that bind these plays together. His most fundamental theme is a lifelong concern with the limitations that define the human condition. These limitations, partially expostulated in the Goethe poem quoted above, are necessary reminders of human weakness, cruelty, and arrogance. The most significant human boundary in Euripides is that of intellect. Mans intellect, his greatest possession, is very often his undoing as he arrogantly constructs theological or materialistic systems of convenience in contradiction to the received knowledge of past traditions. Euripidean drama attempts to reacquaint humanity with its essential nature and its place in the cosmos. To effect this reacquaintance, Euripides needs to present human kind as it actually is in real life.

Euripides was one of the first and most instinctive realists working in any artistic medium. Fifth century Athenians generally considered their mythic characters to have been human beings, and Euripides strove to embody them warts and all upon the Athenian stage. The desire to portray life as it is led Euripides to question many a prejudice about the supposed inferiority of women to men, as well as barbarians to Greeks. His ethical sense did not preclude him from showing that often the wrong person may say the correct thing. Reality as Euripides perceived it is inherently multifaceted.

Euripidess quest to portray existence as it is is itself paradoxical. He was a realist working in a highly stylized art form in a time of great epistemological upheaval. Surely the dualistic vision that informs much of Euripides is derived to some degree from the dialectic methods of thought practiced by the sophists. But this same dualism in Euripides never declines into pure nihilism. In many respects, his work is a devastating assault on the most innovative thought of his age, rationalism and sophism. Rationalists are almost always brought to ruin in his work. Life, if it is to be accurately presented in tragic art, is a mixture of simplicity and complexity, of beauty and ugliness. What we take for granted in human life is usually wrong. Men are not gods.

Next page

![Euripides - Classic Greek Drama: 10 Plays by Euripides in a Single File [NOOK Book]](/uploads/posts/book/43473/thumbs/euripides-classic-greek-drama-10-plays-by.jpg)

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.