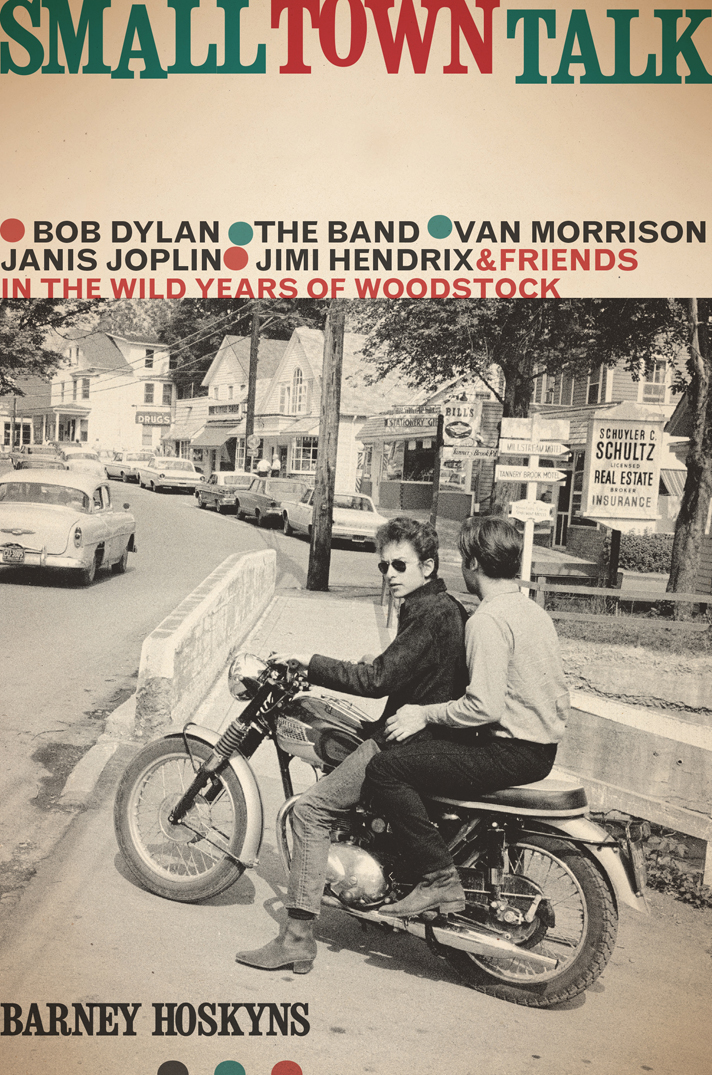

Small Town Talk

Copyright 2016 by Barney Hoskyns

Map Kevin Freeborn, 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. For information, address Da Capo Press, 44 Farnsworth Street, 3rd Floor, Boston, MA 02210.

Designed by Jack Lenzo

Set in eleven point Aldine by The Perseus Books Group

Cataloging-in-Publication data for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN: 978-0-306-82321-3 (e-book)

Published by Da Capo Press

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

www.dacapopress.com

Da Capo Press books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In memory of my father

Table of Contents

Guide

Contents

Listen, oh dont it get you,

Get you in your throat

Van Morrison, Old Old Woodstock (1971)

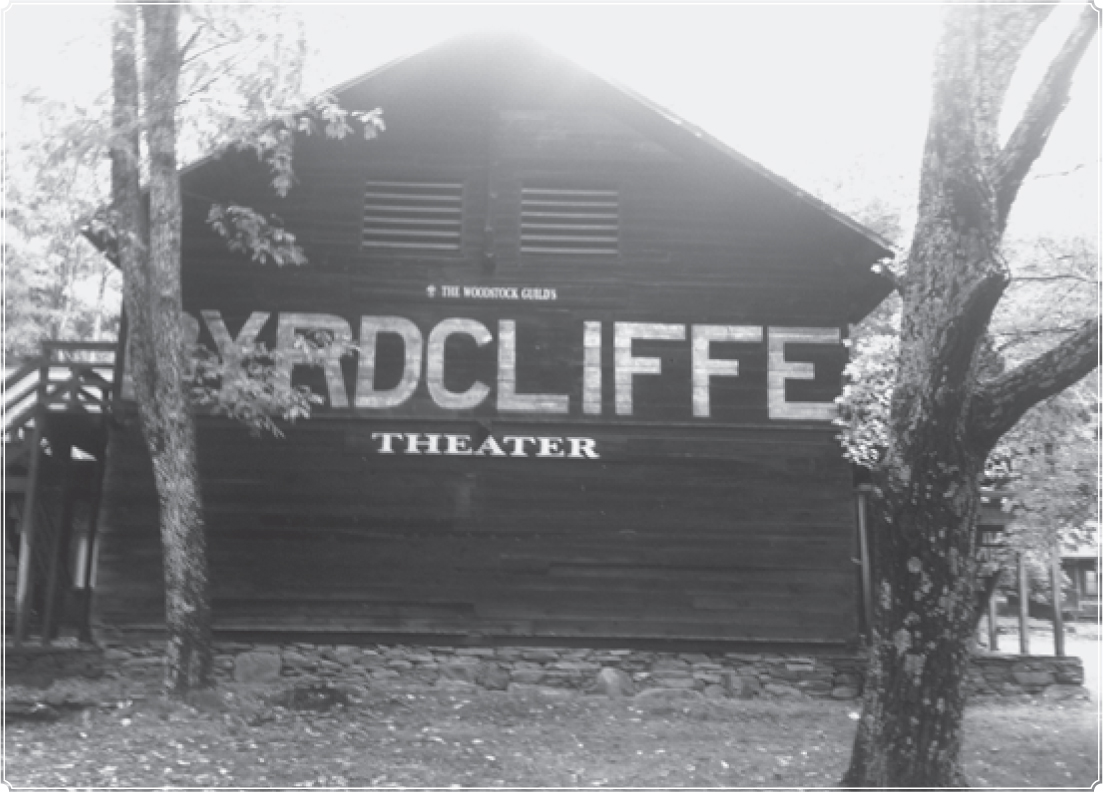

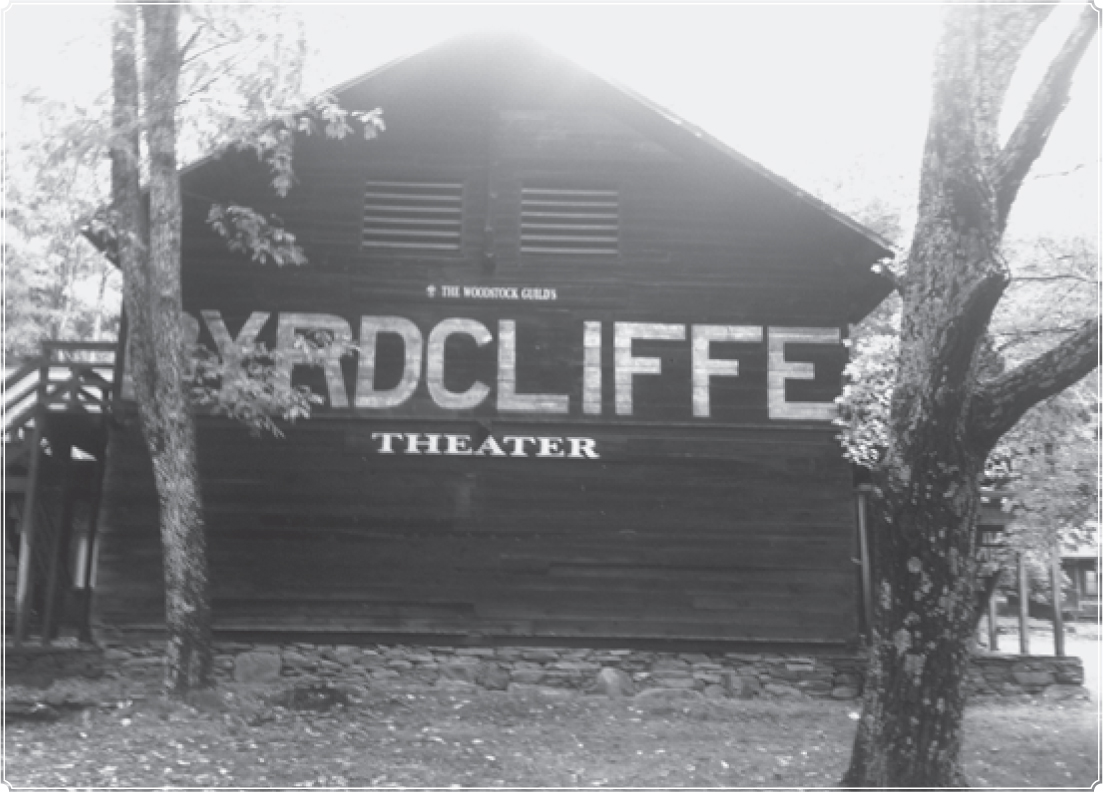

IF YOU LISTEN, it all comes back. It comes full circle here on a rain-spotted night in the heart of the old Byrdcliffe art colony in New Yorks Catskill Mountains, inside a small theatre built of dark cedar a hundred years ago. A son of Old Old Woodstock takes the stage with a micro-ensemble of guitarist, cellist, and fiddler and says, Were so happy youve joined us in this historic place in the woods. This is a significant mystical zone that we inhabit.

Simone Felice is invoking our surroundings: the foothills of Overlook Mountain, a place sacred to Algonquins centuries before it became a destination and settlement for artists and craftspeople and bohemians of the early twentieth century. He is also a child of Woodstocks musical history, the thirty-seven-year-old son of a carpenter who came to the Catskills for the 1969 Woodstock Music & Art Fair and never left.

In 2005, Felice and his brothers, Ian and James, formed a group in the mode of Bob Dylan and the Band, drawing on the woodsy influence of the basement tapes recorded by Dylan and his Canadian friends in a pink house due east of here in West Saugerties. Now putting the finishing touches to his second solo album, Felicelike Dylan in 1967has turned his back on modern technology and urban overstimulation. Hes a country boy whose primarily acoustic music grows out of the land and the trees in nearby Palenville, where he and his brothers were raised. You and I belong to the woods! he exhorts in a song for his baby daughter, Pearl.

As he switches from strummed acoustic to a very unfancy drum kit, the handsome man with the Terence Stamp eyes morphs for a minute into the Bands late drummer Levon Helm, with the same sparse beard and curling hair, the same shapes thrown on the drum stool. This is a song, he announces, about falling madly in love with a hooker on heroin. And thus, in an instant, do we get the dark flipside to Woodstocks bucolic rock idyll. For as Felice also knows, this small town, housing as it did so many maverick talents, fostered a scene of damage and dysfunction that endures to this day. It pulled in all manner of wannabes and hangers-on, alcoholic philanderers, dealers in heroin and cocaine, and left at least one generation of messed-up children with no direction home.

Just a few hundred yards away from the theatre is Hi Lo Ha, the house Bob Dylan bought in the summer of 1965, where he lived for a few apparently happy years as a self-reinvented paterfamilias in spectacles and seersucker jackets. Yet Dylan himself got out while he could, removing his young family for a while to a more remote property on Ohayo Mountain Road before abandoning altogether the town that had given him succor and sanctuary.

Van Morrison was another who came for the clear mountain air and the stunning views from atop that same Ohayo Mountain. Morrison, however, recoiled at the cultural aftereffects of the Woodstock festival and went on his curmudgeonly way to Northern California. Others stayed and came to sticky ends as they sank into the hedonistic mire of Woodstocks bars and clubs. The Band returned from a glitzy sojourn in Malibu and remained forever linked to Woodstock and its satellite hamlet, Bearsville. In 1987, a year after the groups most soulful singer, Richard Manuel, hanged himself, transplanted Chicago harp master Paul Butterfield died of peritonitis in Los Angeles. Other Woodstock denizens perished of similarly premature causes: Tim Hardin, Karen Dalton, Jackson C. Frank, Wells Kelly, and more. The Bands Rick Danko suffered a fatal, drug-induced heart attack in 1999. Folk legend John Herald killed himself in 2005.

Then there were the survivors. After decades of scuffling and financial disaster, Levon Helm rallied for a last wind of Woodstock life with the beloved Rambles shows staged in his wooden barn off Plochmann Lane. And perhaps it is more than cosmic coincidence that, as I sit tonight in Byrdcliffe and think of Helm reborn as Simone Felice, Im unable to expunge from my mind an email Ive just received from Sally Grossmanwidow of the Bands and Dylans old manager Albert Grossmanaccusing me of taking Helms side in his long and fruitless war against her late husband and Band guitarist Robbie Robertson. I should be basking in the peace of Felices mystical zone, yet I sit here and feel the sting of Sallys attack. A few days later I receive a second email from her, demanding I leave town and vowing to sue if I quote from the email.

Theres a veil of secrecy around all this stuff, the folk singer Artie Traum told me when I first visited Woodstock in the summer of 1991. And for no particular reason, because theres really nothing to hide. I dont think there are any skeletons that arent already public. But one of the whole things that Dylan started was Dont talk to anybody.

A FEW DAYS after Felices Byrdcliffe show, Im motoring slowly up a driveway that Dylan would once have known like the back of his hand. In the passenger seat is David Boyle, a cantankerous carpenter who, fifty years ago, was obliged to vacate a cottage on this very property to make way for Dylan. Having been fired by Sally Grossman some years ago, Boyle is urging me on toward the big Bearsville house her late husband bought in 1964, dismissing my fears that she will see us and call the police. If you havent telephoned you are trespassing, declared a sign that Boyle once put up for the Grossmans at the entrance. We havent telephoned.

Sally has her queen of Sheba thing, Boyle mutters at my side. Best just to creep along. Creep along is what I accordingly do, though I find it hard to see how it will make us any less visible to Mrs. Grossman, whose lights are clearly on in the late-afternoon twilight. As I steel myself, gripping the wheel with clammy hands, Boyle points out various landmarks of interest, including the cottage he had to give up for Dylan. Finally I exhale a giant sigh of relief as we head back down the driveway and exit the property.