Contents

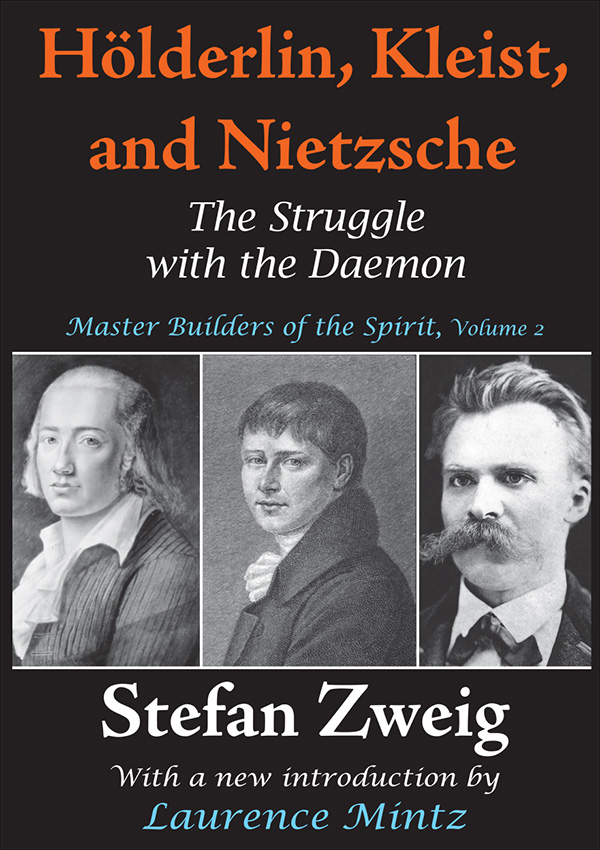

Hlderlin, Kleist, and Nietzsche

Hlderlin, Kleist, and Nietzsche

The Struggle with the Daemon

Master Builders of the Spirit, volume 2

Stefan Zweig

with a new introduction by

Laurence Mintz

Originally published in 1939 by Viking Press.

Published 2011 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

New material this edition copyright 2011 by Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2009041225

The Library of Congress has cataloged volume 1 of this work as follows:

Zweig, Stefan, 1881-1942.

[Three master builders]

Balzac, Dickens, Dostoevsky : master builders of the spirit /

Stefan Zweig.

p. cm.

Originally published: Master builders, a typology of the Spirit.

New York : Viking Press, 1930.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-4128-1047-0 (alk. paper)

1. Fiction--19th century--History and criticism. 2. Balzac, Honor de, 1799-1850--Criticism and interpretation. 3. Dickens, Charles, 1812-1870--Criticism and interpretation. 4. Dostoyevsky, Fyodor, 1821-1881-Criticism and interpretation. I. Title. II. Title: Master builders of the spirit.

PN3499.Z94 2009

809.3034--dc22

2009041225

ISBN 13: 978-1-4128-1135-4 (pbk)

TO

SIGMUND FREUD

I love those who know not how to live except through surrender, for they are on the way elsewhere.

Friedrich Nietzsche

CONTENTS

Safety first!Moritz Zweig

There is no safety.Arthur Schnitzler, Paracelsus

In the decades between the two world wars, Stefan Zweig (1881-1942) was probably the most widely translated and read serious author in the world. He was the writer who most thoroughly embodied the popular image of the good European and the ideals (as they were then conceived) of humanist uni-versalism and apolitical internationalism. Amazingly prolifi c, his indefatigable activity as fi ction writer, poet, essayist, biographer, translator, dramatist, librettist, and cultural ambassador at large was driven by a fervent, near religious faith in the supranational unity of Western culture that bore its fi nest fruit in the Renaissance humanist and Enlightenment values of reason, tolerance, progress, peace, and the intellectual fi gures who personifi ed them while facing down their enemies.

The cultural readjustments of the postwar years changed all of that. Zweigs reputation and popularity, at least in the English-speaking world (he has always been popular in France) dwindled along with those of such now dusty names as Jules Romains, Ren Schickele, Georges Duhamel, Lion

Feuchtwanger, Jakob Wassermann, Henri Barbusse, and Romain Rolland. Most of his books went out of print, and he was remembered mainly for a single short story, Letter From an Unknown Woman, the source of Max Ophuls great fi lm of the same title; thus his name became associated (somewhat mislead-ingly) with the alt Wien of Strauss music, moonlit walks in the Prater, cafes, closed fi acres, and chambres separes. His Viennese friends and contemporaries, Arthur Schnitzler, Joseph Roth, and Hugo von Hofmannsthal suffered a similar eclipse, but in the case of Zweig this had less to do with literary fashion than with his very public role as literary statesman and the dated, nave quality of his above-the-fray idealism in the shadow of the wars devastation, the Holocaust, and the ideological battles of the Cold War.

Something of Zweigs postwar fall from grace was anticipated in Hannah Arendts scornful review (1943) of his posthumously published memoir, The World of Yesterday. Zweig, together with his second wife, had committed suicide in Brazilian exile, a gesture of despair that unsettled and angered the German migr community. Thomas Mann, the erstwhile unpolitischen, now its unoffi cial leader, had turned all his extra-literary efforts to the fi ght against Nazism, and refused to write more than a perfunctory tribute, considering Zweigs act a dereliction of duty. By contrast, Arendt, then at the height of her Zionist commitment, went after Zweig without mercy, portraying him as an ivory tower aesthete who regarded Nazism first and foremost as an affront to his personal dignity and privileged way of life. Lacking any coherent political viewpoint, he is unable in his recollections, she charged, to trace the chain of causality from the false security of the late Habsburg decades to the present catastrophe. His blinkered portrayal of Viennese life, in Arendts view, hardly ventures beyond the closed circle of its cultivated bourgeoisie with its even more circumscribed and oblivious Jewish component. She views with contempt the generational transition from money making to cultural activity among Jewish families (which Zweig records with defensive pride) as a regressive retreat from worldly responsibility and knowledge. In its place, Arendt, like the Viennese critic Karl Kraus, sees, not the cultural renaissance Zweig claimed, but a sham theatrical culture of aesthetic surfaces and actorly gestures, not greatness but the image of greatness, a portent of Hollywood.

There is some rough justice to Arendts criticism, but her portrayal of Zweig departs markedly from both the tone and substance of his memoir. (A small example: Zweig does not praise Karl Lueger, the anti-Semitic mayor of Vienna as an able leader and kindly person. Like every subsequent historian of Vienna, he acknowledges Luegers undeniable political skills, but emphasizes that underneath the suave exterior der schne Karl was Hitlers prototype with his own Streicher, a certain mechanic named Schneider.) At points, Arendt elides her ostensible subject to create a composite fi gure of the typical

Viennese-Jewish intellectual caring only for fame and success and who may or may not be identifi able with Zweig. Thus,

Contemporary success was also the only criterion that remained for the general geniuses, detached from their achievements and considered only in light of their inherent greatness. In the fi eld of letters this took the form of biographies describing no more than the appearance, the emotions and the demeanor of great men. This approach not only satisfi ed vulgar curiosity about the kind of secrets a mans valet would know; it was also prompted by the belief that such idiotic abstraction would clarify the essence of greatness.

Zweig was, of course, famed for his best-selling biographies of great men, but these books (the Master Builders trilogy in particular) intended to distill the creative psychology and historical signifi -cance of their subjects. Personal trivia and gossip of the sort to debunk the subject (the Great Man is not so great) or fl atter the reader (the Great Man is just like me) are not to be found.