Stefan Zweig - Nietzsche

Here you can read online Stefan Zweig - Nietzsche full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Steerforth Press, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

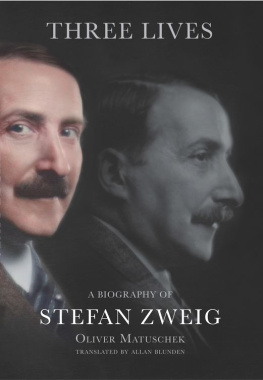

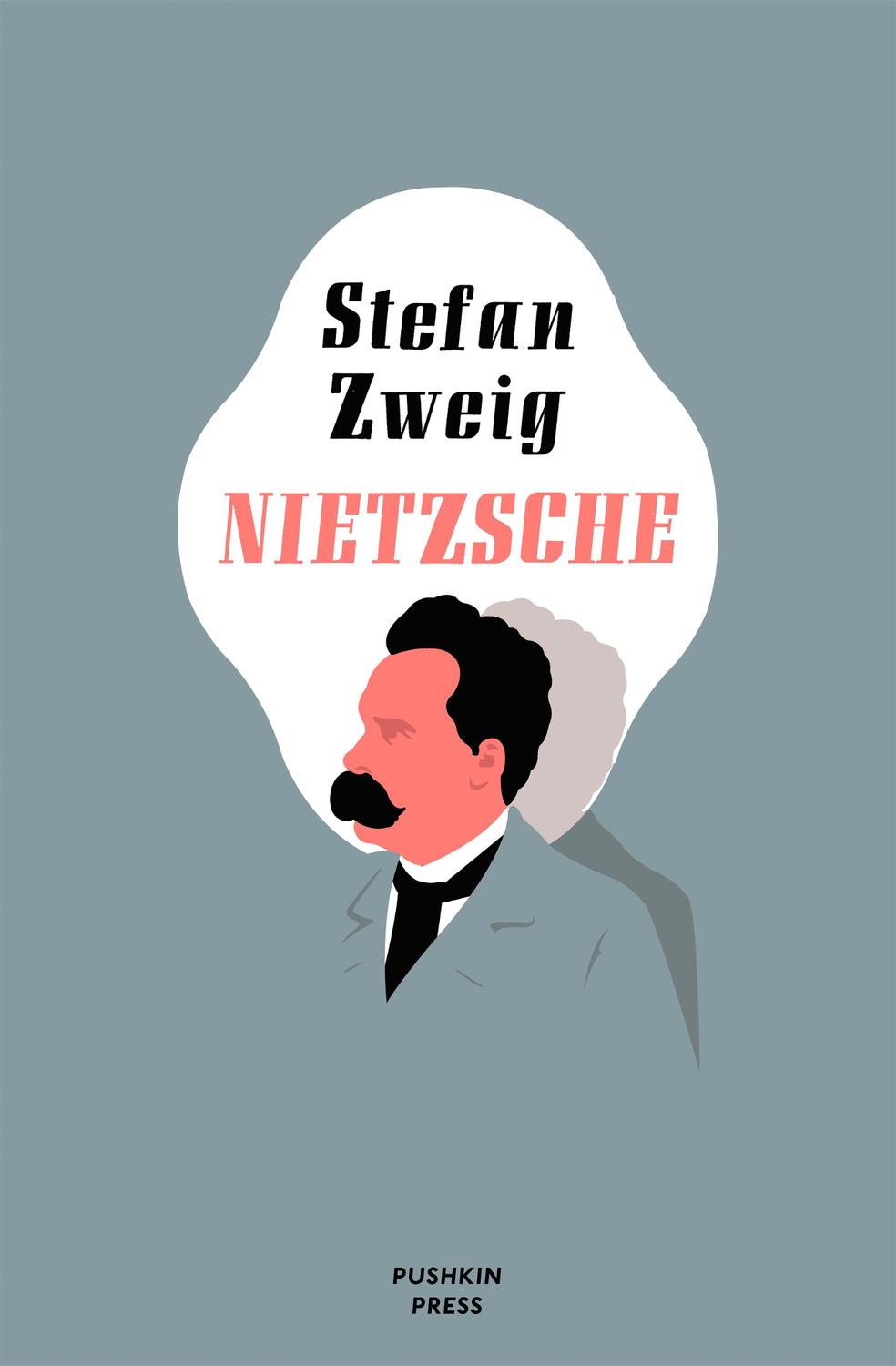

- Book:Nietzsche

- Author:

- Publisher:Steerforth Press

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Nietzsche: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Nietzsche" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Nietzsche — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Nietzsche" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

I think of myself as a philosopher only in the sense of being able to set an example

Untimely Meditations

vi

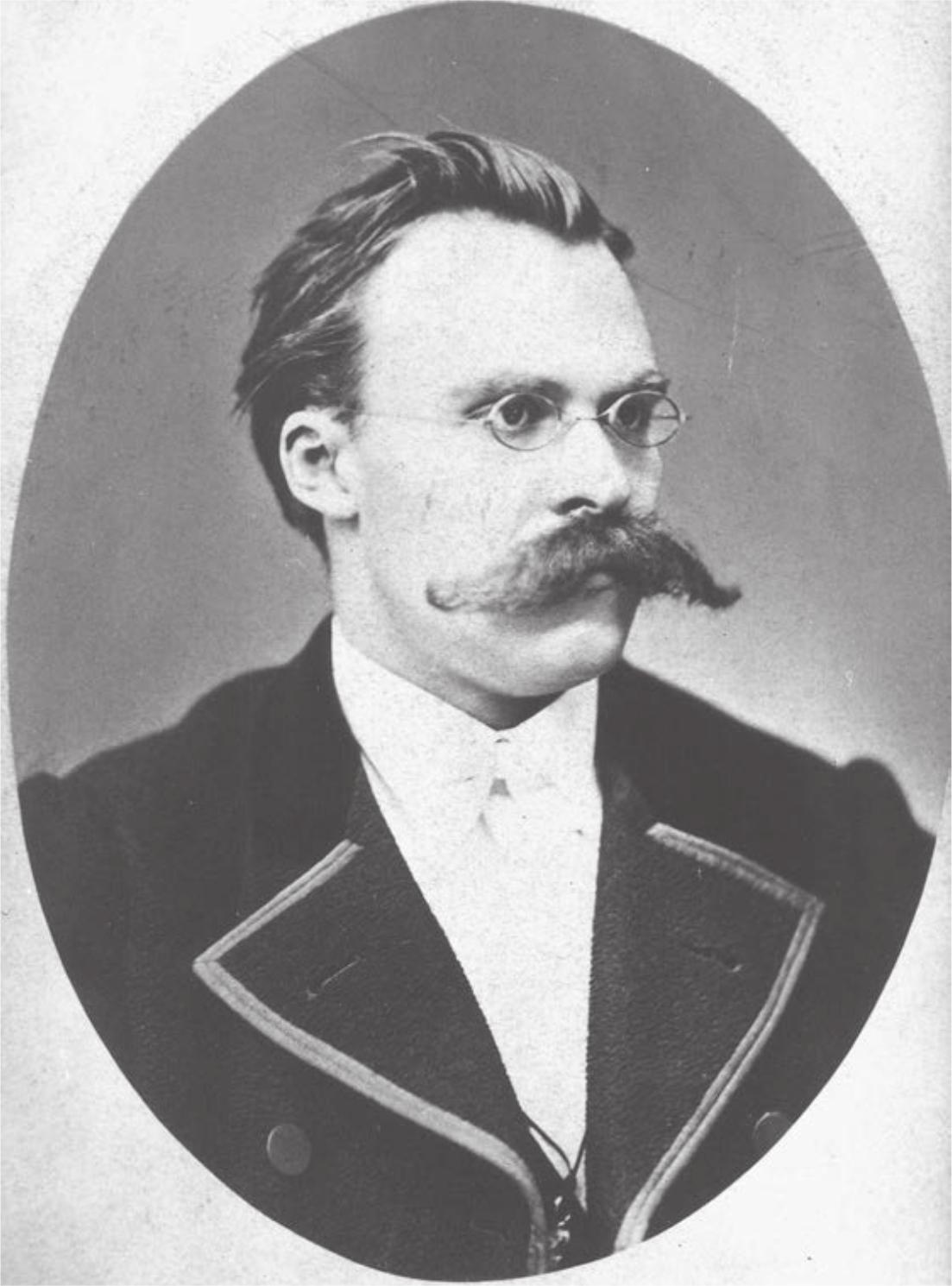

Nietzsche during his professorship in Basel

My relationship with the present age is from now on to be war of knives.

Friedrich Nietzsche

Stefan Zweigs essay on Nietzsche constitutes the third part of a trilogy within a trilogy, a vivid and impassioned psychobiographical exploration of one major figure within a group of globally renowned artists who had decisively influenced Zweigs own spiritual trajectory, or with whom he had travelled across his maturing literary life in a protracted fraternal kinship. As in his other profiles of more modest length, dedicated to numerous artists, writers and musicians, many of which have never been translated into English, Zweig employs the same deft psychical probing and an almost febrile passion for unearthing his subjects inward anxieties and necessarily thwarted ambitions, the very skills that entranced so many readers of his fiction both in his lifetime and to the present day. Through the 1920s, at regular intervals, Zweig published successive installments of these trilogies to be known as Die Baumeister der Welt, which in English became known as the Master Builders series. Each triumvirate was selected due to an espoused spiritual or visionary commonality, a correspondence of temperament or psychology. The first of these, Drei Meister (Three Masters) (1920), comprised Balzac, Dickens and Dostoyevsky, then came Der Kampf mit dem Dmon (The Struggle with the Demon) (1925), focusing on Hlderlin, Kleist and Nietzsche, and finally Drei Dichter ihres Lebens or (Adepts in Self-Portraiture) (1928), which turned to Casanova, Stendhal and Tolstoy. The whole series was then assembled and published as one in 1935. The Struggle with the Demon appeared viii in English for the first time in 1939, at a moment of great upheaval and uncertainty for its author as Europe prepared to face Hitlers threat. One name notably absent from this list of literary grandees is that of Montaigne, whom Zweig only properly absorbed in exile in Brazil at the end of his life, when, in a desperate search for mental sustenance, he stumbled on a copy of the essays. Had he come to Montaigne earlier it would seem inconceivable, given his eleventh hour reverence for the great essayist, that he would not have been included. Zweigs last literary portrait essay was in fact dedicated to Montaigne, whose eloquent thoughts on suicide and nobleness, notably in the essay A Custom of the Isle of Cea, crucially influenced Zweigs decision to take his own life.

Of the three trilogies, it is arguably those peculiarly extreme demands foisted on the tortured spirits depicted in The Struggle with the Demon that make it appear the most compelling and relevant to a contemporary audience, perhaps too because the three spirits selected represent an artistic and intellectual phenomenon at odds with the seemingly restrained and financially secure existence of Zweig himself and what appears to be the incremental literary advancement of a prolific man of letters. Having said this, inwardly Zweig himself was no stranger to his own demon, that of angst, periodic bouts of withering depression and a latent suicidal impulse, a preoccupation that perennially leaked into the trajectories of his fictional characters and eventually crystallized in his own demise. Though it should be remembered that Zweig in contrast to outward appearances, never considered himself a calmly advancing, measured person, but quite the opposite, a man afflicted by delirious passions and anxieties which he could barely restrain. This dichotomy between Zweigs inner propensity to morbid despair and his outward appearance of composure, personal warmth and his qualities as a literary ix statesman and spokesman only heightened the shock, outrage and disbelief at his suicide in Petropolis in February 1942.

Zweig has, not unsurprisingly, been criticised for elements of hagiography in some of his biographies and a glance at portions of rhetorically exultant prose makes such a criticism inevitable. It is true that, especially in his early biographies of those he revered, such as the Belgian poet Emile Verhaeren, or the French writer Romain Rolland, these works might appear today as mere indulgent opportunities to lavish praise on these chosen overseers of Zweigs own spiritual odyssey for their perceived literary purity. But if one looks closer at such biographies, which are in fact nothing of the kind, but more ardently persuasive romantic hymns to their subject, there are secreted between the hot-blooded lines numerous subtle insights and valuable discernments which have only managed to germinate and peep through the undergrowth of emotion by drawing an unlikely nutrition from the relentlessly pounding ram of exultation. This juxtaposition of ecstasy and insight forms a key element in the composition of Zweigs typical essay style and is clearly evident in his work on Nietzsche. With Zweig at the controls, the reader must simply strap themselves in and enjoy the ride, taking in the opulent landscapes that appear on either side, the pictorial replenishments offered by Zweigs urgent conviction and obedient imagination. Yes there is repetition; Zweig has a tendency to over-egg the point by reiterating it, but these waves which parade their dauntless energy through the text are all closing in on the one shoreline, in this case to delineate the reality of the fall of Nietzsche in the most plausible terms, and in the most humane manner. Zweig was above all else a humanitarian, who saw culture not as one of numerous tributaries converging on a life richly experienced, but as its main artery, and in Nietzsche he sees not only a complex historical situation involving one great individual of the spirit, but x the less resounding tragedy of a solitary misunderstood man hampered by ailments and despair, desperately working for the self realization of a humanity which will always remain blind and fatally harnessed to foreground conclusions.

Does this not then in some sense correspond with Zweigs own personal mission? The noble folly of his ingenuous ideal of European intellectual union and cultural profligacy, in some sense traces the ecstatic crescendo of the great philosopher and the unbearable uninhabited ice floe of its diminuendo. Of course, Nietzsches ambitions are far more complex, but there is enough symbolic kinship here for Zweig to place Nietzsche as the obvious presiding father of the serviceable current stock of good Europeans. For it was these single-minded, pure intentioned leaders, these noble men of sacrifice, these men of example, of whom Nietzsche was but one, which Zweig revered. But Zweig not only supported these dead masters by applauding their exploits and delineating their natures in books; he physically supported one still living by actively promoting his work in Germany on a grand scale. This was the case with the Belgian poet Emile Verhaeren, who was barely known in Germany before Zweig, with customary zeal, determined to address the issue. Still then in his mid twenties, Zweig translated Verhaerens poetry and pushed his works and personality vigorously into the domain of German letters, organizing lecture tours, readings, and commanding successive editions of the older poets works. Verhaerens fame in Germany and his consequent influence on German expressionist poets such as Georg Heym and Jakob van Hoddis, then his export to Russia and hence to the attention of Blok and Mayakovsky, was largely down to Zweigs almost fanatical appreciation of his work, that sense of truth and honesty, which the raw, fiery, earth bound voice of Verhaeren symbolized for a young writer keen to leave behind the self-regarding literary cliques and contrivances of the Viennese society into which he had been born. xi

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Nietzsche»

Look at similar books to Nietzsche. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Nietzsche and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.