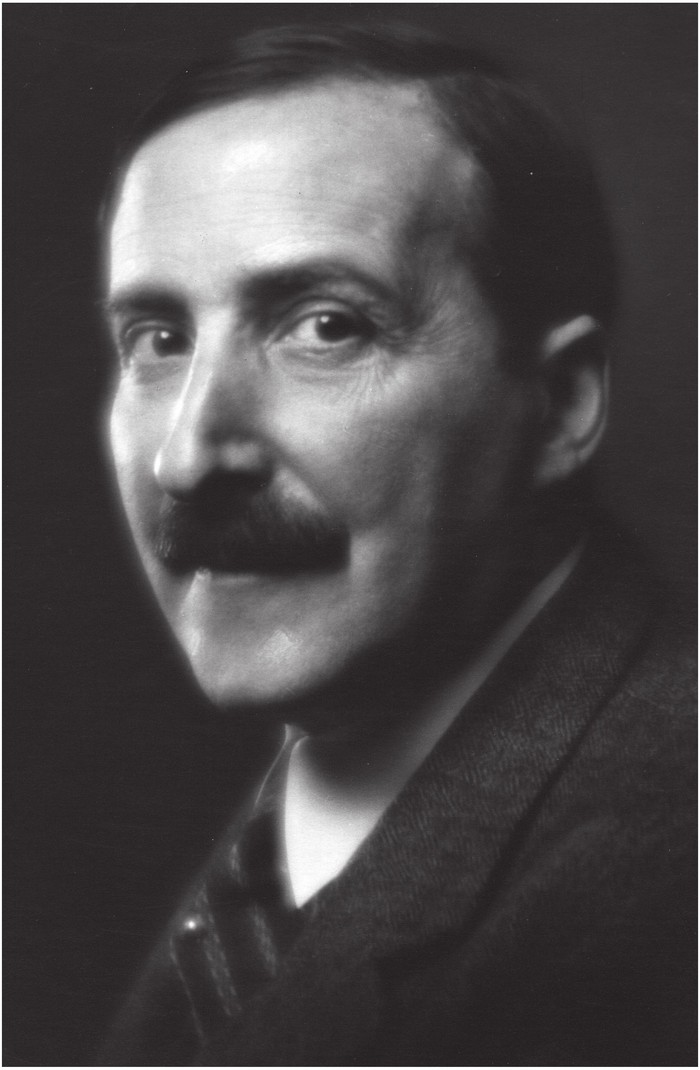

The outward impression that one gets of this singular man blurs many a notion that one has formed of the writer Stephan Zweig. A meeting with him is in no sense a disappointment, it is just very different from what one expects. His demeanour is so cautiously reserved and unassuming, that in conversation about ordinary everyday things one forgets about the powerful and vigorous language of his short stories and novels, his poems and plays. One is quite won over by the enchanting simplicity of his appearance and character.

Egon Michael Salzer in the Neues Wiener Journal August 1934

In July 1940 the journalist H O Gerngross met in New York with one of the most famous European writers of his day, Stefan Zweig. The two men talked about times past and future plans, about brilliant successes and dark forebodings. With the Anschluss of 1938 Zweigs native Austria had been incorporated into the German Reich; his books were banned in both countries, and as a Jew he could not even think about returning home. At the time of the interview the Second World War had been raging for almost a year, and the Netherlands, Belgium and northern France had just been occupied by the German Wehrmacht.

Despite all the setbacks and defeats, Zweig planned to carry on devoting all his energies to writing and producing new books for his reading public, even if that audience was a great deal smaller now in Germany as a result of the book bans. The journalist Gerngross tells us that he saw on the little writing table in the hotel room and on the chair next to it, [ ] sheets of paper, squared sheets of paper from an ordinary tear-off pad. They are covered with that neat, elegant handwriting that we know so well. And the purple ink is still there. In the preceding decades Zweig had penned thousands of manuscript pages and letters in this, his preferred shade of ink. But now he was preparing a work of a different kind. As Gerngross reveals to his readers:

Stefan Zweig is taking a break from literature and belles-lettres. A biography of Balzac, planned for many years, remains unfinished, not least because the author

And in due course Gerngross published his article in the migr newspaper Aufbau under the title Drei Leben. Looking back on his life story, Stefan Zweig viewed it in terms of three distinct phases. The first life, which had begun in 1881 with his birth as the son of a weaving-mill owner in Vienna and ended with the First World War, had been lived in the seemingly secure world of the affluent bourgeoisie. His second life had begun, full of hope, in his new elective home of Salzburg, and had brought him an unparalleled rise to eminence as one of Europes most widely read and translated authors, before ending with his departure from Austria. His third life, which he spent in exile, had not long begun at the time of the interview: it would turn out to be the shortest of the three.

As he was writing his memoirs Zweig soon realised that he was not really telling the story of his life, but rather painting a panoramic picture of the age. Many of his own experiences are woven into the narrative, but his private life as such is completely glossed over. His two wives and some of his closest friends do not get a single mention in the entire manuscript. So the intended title now seemed less appropriate than originally thought, given that a book entitled My Three Lives would clearly have led readers to expect a much more personal account than the one Zweig had actually written. In the end the work appeared after his death as Die Welt von Gesternthe final (and very appropriate) title chosen by the author.

For any examination of Zweigs lifeincluding the present study, therefore his own book of memoirs is clearly of central importance. But for anyone who wants to understand not only the writer and contemporary observer Stefan Zweig, but also the man and his private life, in order to paint a more accurate picture of his three lives, there is now a wealth of published material available, starting with the collected edition of his works and diaries, and including various volumes of letters and exchanges of letters from the vast correspondence that Zweig conducted throughout his life. And yet many questions remain unanswered. The much-quoted words Your writings, after all, are only a third part of who you are appear in a letter written to him in 1930 by his first wife Friderike. The passage in

It is true that even in his younger years Stefan Zweig rarely spoke openly about himself. Even to people who knew him well he came across as buttoned-up, and in many ways he remained a riddle even to his close friends. But happily Friderike did not keep her knowledge to herself. In addition to a number of historical accounts she also wrote several books of memoirs in the post-war years, which contain important clues and aids to interpreting the life and work of her former husband, and which have playedand continue to playa key role in biographical research. Her book Stefan Zweig, wie ich ihn erlebte [Stefan Zweig as I Knew Him] was published in German as early as 1947. Five years later, following numerous shorter newspaper articles and interviews, extracts from the correspondence they had conducted between 1912 and 1942 were published in book form. Friderike Zweig was now living in the USA, where she died in 1971, but over the years she visited her former homeland on several occasions, giving lectures in Vienna and other places and reading from her works at well-attended literary events. In 1961 her book Stefan ZweigEine Bildbiographie [Stefan ZweigA Biography in Pictures] appeared, followed three years later by Spiegelungen des Lebens [Reflections of Life], which is more of an autobiographical work, although several important chapters are devoted to Stefan Zweig.

As we now know, Friderike Zweigs publications are tainted by a blend of more or less adroit manipulation and concealment of facts (and this for more or less understandable reasons). The first thing to say is that she never wrote her accounts with the intention of producing works of scholarship, but instead recounted her memories in the style of fictional narrative, with an eye to the interests of her readers. And for many of the events she described she no longer had much, if indeed anything, in the way of documentary sources, so that she was forced at times to rely on her own memory. Consequently it is easy to understand how errors have crept in when describing events that took place in some cases

Like the published correspondence, Friderikes volumes of memoirs also proved quite popular with the reading public, and only a few individuals were in a position to voice informed criticism of their reliability at the time of their publication. One such person was Stefan Zweigs elder brother Alfred, who had left Vienna in 1938 and settled in New York, where he lived until his death in 1977. The walls of his apartment overlooking Central Park were hung with numerous photographs of family members. Many of these pictures showed his famous brother Stefan, who had committed suicide in 1942 together with his second wife Lotte. Far from his European homeland, Alfred not only had to contend in the post-war years with repeated and thoroughly objectionable questions from every possible quarter about his brothers Communist activities (since people were constantly confusing Stefan Zweig with Arnold Zweig), but also had to fend off other attacks as a result of Friderikes activities.