Stefan Zweig - Beware of Pity

Here you can read online Stefan Zweig - Beware of Pity full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2006, publisher: NYRB Classics, genre: Art. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

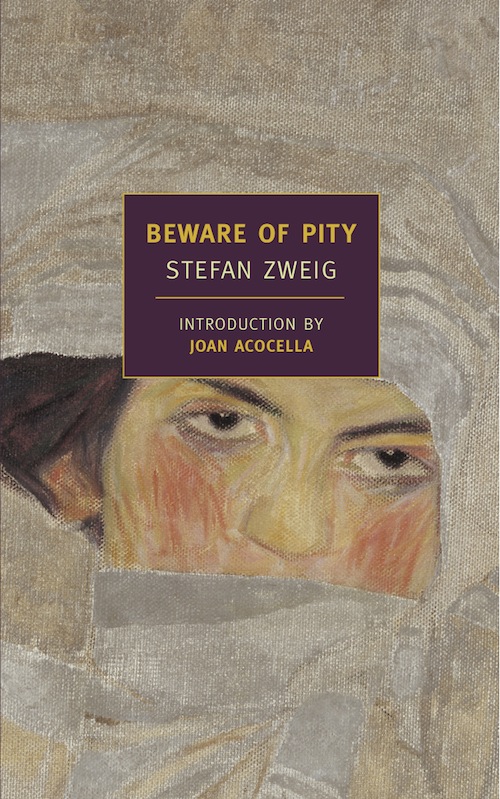

- Book:Beware of Pity

- Author:

- Publisher:NYRB Classics

- Genre:

- Year:2006

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Beware of Pity: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Beware of Pity" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Wes Anderson on Stefan Zweig: I had never heard of Zweig...when I just more or less by chance bought a copy of Beware of Pity. I loved this first book. I also read the The Post-OfficeGirl. The Grand Budapest Hotel has elements that were sort of stolen from both these books. Two characters in our story are vaguely meant to represent Zweig himself our Author character, played by Tom Wilkinson, and the theoretically fictionalised version of himself, played by Jude Law. But, in fact, M. Gustave, the main character who is played by Ralph Fiennes, is modelled significantly on Zweig as well.

Stefan Zweig was a dark and unorthodox artist; its good to have him back.--Salman Rushdie

The great Austrian writer Stefan Zweig was a master anatomist of the deceitful heart, and Beware of Pity, the only novel he published during his lifetime, uncovers the seed of selfishness within even the finest of feelings.

Hofmiller, an Austro-Hungarian cavalry officer stationed at the edge of the empire, is invited to a party at the home of a rich local landowner, a world away from the dreary routine of the barracks. The surroundings are glamorous, wine flows freely, and the exhilarated young Hofmiller asks his hosts lovely daughter for a dance, only to discover that sickness has left her painfully crippled. It is a minor blunder that will destroy his life, as pity and guilt gradually implicate him in a well-meaning but tragically wrongheaded plot to restore the unhappy invalid to health.

Stefan Zweig: author's other books

Who wrote Beware of Pity? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.