THE BIRTH OF BOURBON

THE BIRTH OF BOURBON

A PHOTOGRAPHIC TOUR OF EARLY DISTILLERIES

PHOTOGRAPHS BY CAROL PEACHEE FOREWORD BY JIM GRAY

Copyright 2015 by Carol Peachee

Published by the University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Peachee, Carol.

The birth of bourbon : a photographic tour of early distilleries / photographs by Carol Peachee ; foreword by Jim Gray.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-8131-6554-7 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8131-6585-1 (pdf) ISBN 978-0-8131-6584-4 (epub) 1. Bourbon whiskeyHistorySources. 2. DistilleriesKentuckyHistorySources. 3. Abandoned buildingsKentuckyPictorial works. 4. Industrial archaeologyKentucky. 5. Photography, Industrial. I. Title.

TP605.P43 2015

663'.52dc23

Due to variations in the technical specifications of different electronic reading devices, some elements of this ebook may not appear as they do in the print edition. Readers are encouraged to experiment with user settings for optimum results.

Member of the Association of American University Presses

FOR MONICA

CONTENTS

by Jim Gray

FOREWORD

Where do we find art? Anywhere. Everywhere.

Take a look at Carol Peachees art... photographs of the long-abandoned and retired distilleries from Lexingtons Distillery District and throughout the Bluegrass State.

As early as 1810, there were some 140 distilleries operating in central Kentucky, and approximately 2,000 in all Kentucky. By 1987 the bourbon market had decreased dramatically, and many distillery plants were abandoned, while other distilleries severely cut back production. Now spirits are once again being distilled in the Bluegrass, and several thousand tourists have visited the area at the west end of Lexingtons downtown.

Thanks to the vision of creative entrepreneurs, after decades of people passing by these buildings without giving them a thought, several years ago Lexington realized theres once again a lot of potential in the Distillery District and in the states forgotten distilleries. Exciting initiatives are under way to develop the area, using the historical buildings for shops, restaurants, housing, entertainment, breweries, craft distilleries, and more.

C. S. Lewis, the author of The Chronicles of Narnia, wrote of books that had baptized his imagination. Carols photographs baptize the imagination for what the Distillery District and the Bluegrass region can yet become. They are a distillation of the regions history and its potential.

Where do we find art? In these pages.

JIM GRAY

Mayor of Lexington, Kentucky

INTRODUCTION

A Visual Archaeology of Kentucky Bourbon Distilleries

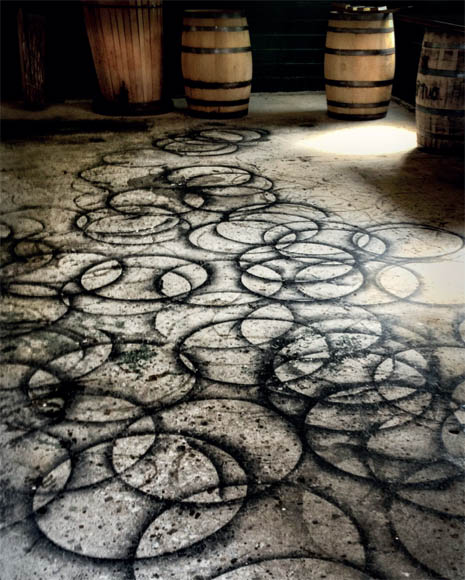

Photography is a practice that reveals. A certain moment, one that is gone as soon as the shutter captures it, becomes static in time. What is no longer there, absence, is present. As well, a distant presence is revealed in the viewers current moment. In the case of a photograph of a historical subject, the photograph reveals something of the past in a moment that itself will be history. For example, several of the structures shown in these pages no longer exist, some have been salvaged for materials, and some have continued deteriorating. Others are in various stages of reclamation or repurposing. Photographed again today, they would look different, which would make some of the images, barely four years old, a relic in their own right.

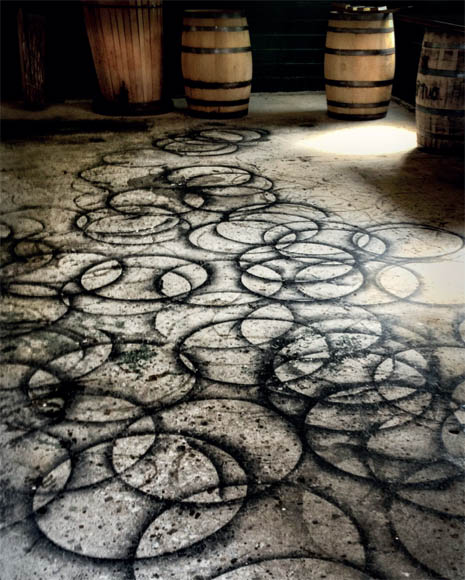

A photograph contains not only the presence of place but also the presence of the photographera point of view, artistic choices, the moment of light, the technology available at the time. Depending on these factors, photographs can reveal what is not noticed by the naked eye. A certain slant of light might create a contrast of edges illuminating a texture or pattern unseen under normal circumstances. Or a telephoto lens might provide a view of a detail beyond a normal viewers physical access. As a result, each photograph is a portrait of many layers, a still life of both the content photographed and the photographer. Yet as literal as the photograph might be, inference is needed to decipher the image.

Archaeology is a common metaphor in the discussions of photography, probably because archaeology and photography share concerns about revelation, inference, presence, and absence. The archaeologist looks for traces of what is no longer, evidence of a once-vibrant existence that is inferred from traces of what can be found or revealed in the now. The presence of this artifact or that structure brings the past into the present, but only by inferencewhat might already be knownor by imagination. The archaeological imagination refuses to acknowledge, quite, the loss of anything, the art historian Kitty Hauser notes, much as the photograph does.and photography are really presenting memoir from a variety of angles, and through many layers, revealed and implied. Together they also try to comprehend, salvage, preserve, and hold on to what is in danger of being lost.

Sitting on the edge of Manchester Street are the historical ruins of the James E. Pepper Distillery. I had never noticed them before, but as I wandered the streets looking for good documentary material, I came upon the abandoned buildings that the Distillery District in Lexington, Kentucky, is named for. In the winter weather, the exterior of the plant looked unremarkable at first glance. Still, I peeked inside the mostly boarded-up lower windows. Everywhere was color, pattern, form, texture, light, space, absence, and presence.

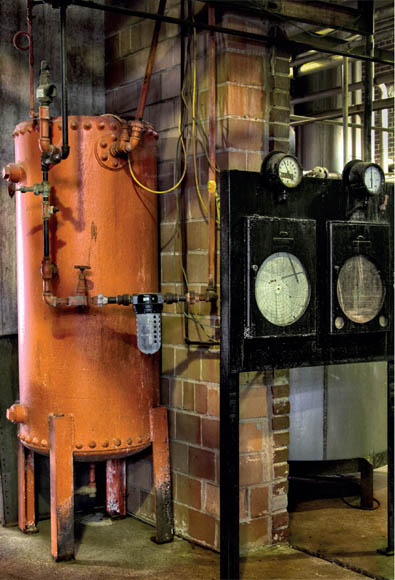

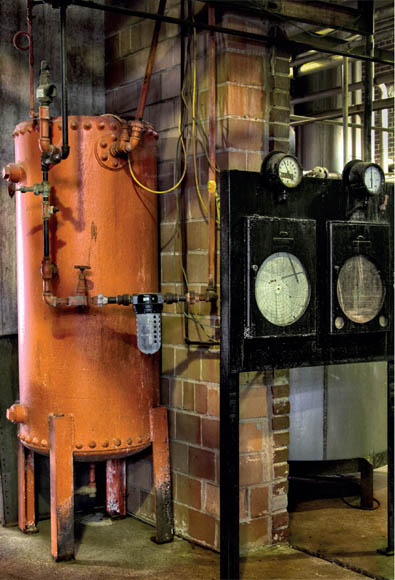

I started photographing the distillery that winter, returning each weekend to spend at least one full day in the cold spaces of the rooms. When I unlocked the outside padlock and stepped into the chilled interiors, it was as if I were stepping into an earthbound Titanic. Here once were heat, noise, human activity, a thriving business, and Kentuckys signature industrybourbon whiskey. Now time and nature floated through the space, transforming the building into a museum and machinery into art. In fact, I came to see the whole distillery as both a museum holding individual works of art, connected works of art, and a work of art itself as a whole. This work of art was still in progress; what had once been here was inferred by what was present.

Next page